4 factors driving 2023’s extreme heat and climate disasters

Michael Wysession, Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis

Between the record-breaking global heat and extreme downpours, it’s hard to ignore that something unusual is going on with the weather in 2023.

People have been quick to blame climate change – and they’re right, to a point: Human-caused global warming does play the biggest role. A recent study determined that the weekslong heat wave in Texas and Mexico that started in June 2023 would have been virtually impossible without it.

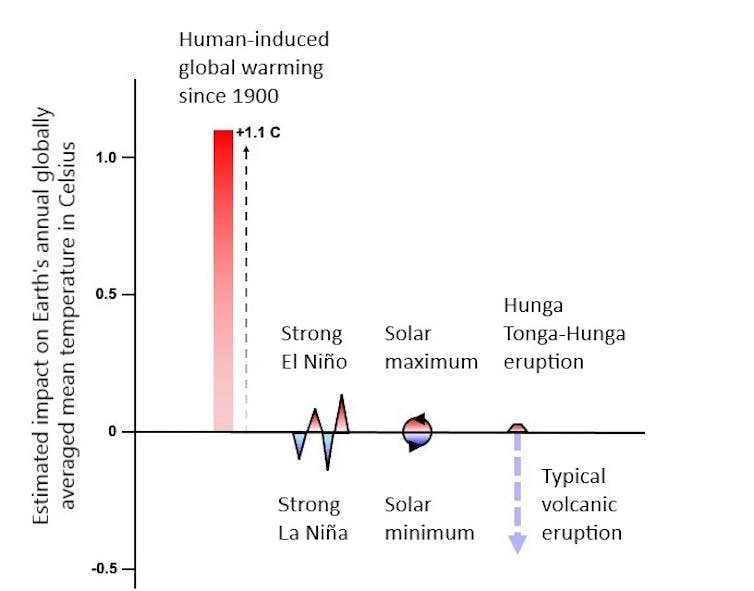

However, the extremes this year are sharper than anthropogenic global warming alone would be expected to cause. Human activities that release greenhouse gas emissions into the atmosphere have been increasing temperatures gradually, at an average of 0.2 degrees Fahrenheit (0.1 Celsius) per decade.

Three additional natural factors are also helping drive up global temperatures and fuel disasters this year: El Niño, solar fluctuations and a massive underwater volcanic eruption.

Unfortunately, these factors are combining in a way that is exacerbating global warming. Still worse, we can expect unusually high temperatures to continue through at least 2025, which means even more extreme weather in the near future.

How El Niño is involved

El Niño is a climate phenomenon that occurs every few years when surface water in the tropical Pacific reverses direction and heats up. That warms the atmosphere above, which influences temperatures and weather patterns around the globe.

Essentially, the atmosphere borrows heat out of the Pacific, and global temperatures increase slightly. This happened in 2016, the time of the last strong El Niño. Global temperatures increased by about 0.25 F (0.14 C) on average, making 2016 the warmest year on record. A weak El Niño also occurred in 2019-2020, contributing to 2020 becoming the world’s second-warmest year.

El Niño’s opposite, La Niña, involves cooler-than-usual Pacific currents flowing westward, absorbing heat out of the atmosphere, which cools the globe. The world just came out of three straight years of La Niña, meaning we’re experiencing an even greater temperature swing.

Based on increasing Pacific sea surface temperatures in mid-2023, climate modeling now suggests a 90% chance that Earth is headed toward its first strong El Niño since 2016.

Combined with the steady human-induced warming, Earth may soon again be breaking its annual temperature records. June 2023 was the hottest in modern record. July saw global records for the hottest days and a large number of regional records, including an incomprehensible heat index of 152 F (67 C) in Iran.

Solar fluctuations

The Sun may seem to shine at a constant rate, but it is a seething, churning ball of plasma whose radiating energy changes over many different time scales.

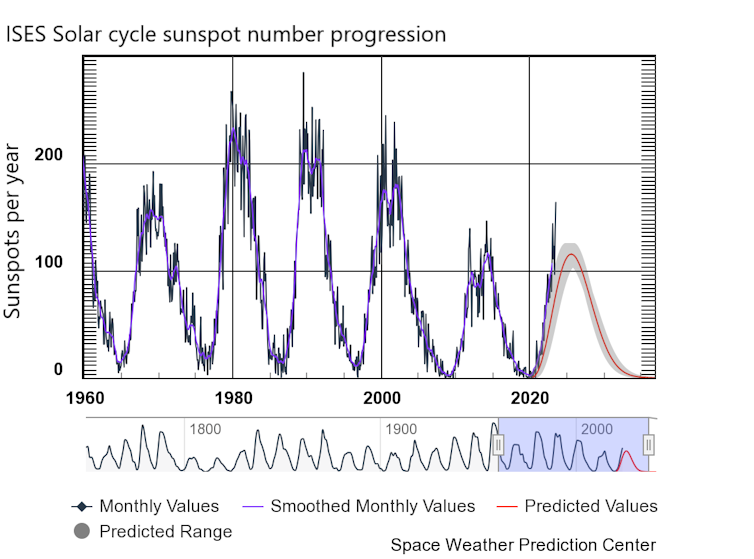

The Sun is slowly heating up and in half a billion years will boil away Earth’s oceans. On human time scales, however, the Sun’s energy output varies only slightly, about 1 part in 1,000, over a repeating 11-year cycle. The peaks of this cycle are too small for us to notice at a daily level, but they affect Earth’s climate systems.

Rapid convection within our Sun both generates a strong magnetic field aligned with its spin axis and causes this field to fully flip and reverse every 11 years. This is what causes the 11-year cycle in emitted solar radiation.

Earth’s temperature increase during a solar maximum, compared with average solar output, is only about 0.09 F (0.05 C), roughly a third of a large El Niño. The opposite happens during a solar minimum. However, unlike the variable and unpredictable El Niño changes, the 11-year solar cycle is comparatively regular, consistent and predictable.

The last solar cycle hit its minimum in 2020, reducing the effect of the modest 2020 El Niño. The current solar cycle has already surpassed the peak of the relatively weak previous cycle (which was in 2014) and will peak in 2025, with the Sun’s energy output increasing until then.

A massive volcanic eruption

Volcanic eruptions can also significantly affect global climates. They usually do this by lowering global temperatures when erupted sulfate aerosols shield and block a portion of incoming sunlight – but not always.

In an unusual twist, the largest volcanic eruption of the 21st century so far, the 2022 eruption of Tonga’s Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai is having a warming and not cooling effect.

The eruption released an unusually small amount of cooling sulfate aerosols but an enormous amount of water vapor. The molten magma exploded underwater, vaporizing a huge volume of ocean water that erupted like a geyser high into the atmosphere.

Water vapor is a powerful greenhouse gas, and the eruption may end up warming Earth’s surface by about 0.06 F (0.035 C), according to one estimate. Unlike the cooling sulfate aerosols, which are actually tiny droplets of sulfuric acid that fall out of the atmosphere within one to two years, water vapor is a gas that can stay in the atmosphere for many years. The warming impact of the Tonga volcano is expected to last for at least five years.

Underlying it all: Global warming

All of this comes on top of anthropogenic, or human-caused, global warming.

Humans have raised global average temperatures by about 2 F (1.1 C) since 1900 by releasing large volumes of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. For example, humans have increased the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere by 50%, primarily through combustion of fossil fuels in vehicles and power plants. The warming from greenhouse gases is actually greater than 2 F (1.1 C), but it has been masked by other human factors that have a cooling effect, such as air pollution.

If human impacts were the only factors, each successive year would set a new record as the hottest year ever, but that doesn’t happen. The year 2016 was the warmest so far, in large part because of the last large El Niño.

What does this mean for the future?

The next couple of years could be very rough.

If a strong El Niño develops over the next year, combined with the solar maximum and the effects of the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai eruption, Earth’s temperatures would likely soar to uncharted highs. According to climate modeling, this would likely mean even more heat waves, forest fires, flash floods and other extreme weather events.

Both weather and climate forecasts have become very reliable in recent years, benefiting from vast amounts of data from Earth-orbiting satellites and enormous supercomputing power for forecasting the flow and interactions of heat and water among the complex components of the ocean, land and atmosphere.

Unfortunately, climate modeling shows that as temperatures continue to increase, weather events get more extreme.

There is now a greater than 50% chance that Earth’s global temperature will reach 2.7 F (1.5 C) by the year 2028, at least temporarily, increasing the risk of triggering climate tipping points with even greater human impacts. Because of the unfortunate timing of several parts of the climate system, it seems that the odds are not in our favor.![]()

Michael Wysession, Professor of Earth, Environmental, and Planetary Sciences, Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.