Behind the Latter-day Saint church’s vast wealth are two centuries of financial hits and misses

© Pogonici - iStock

Benjamin Park, Sam Houston State University

During the first weekend of April 2023, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints will hold its semiannual General Conference in Salt Lake City. Tens of thousands of members will attend in person, with millions watching from home.

Over two days, Latter-day Saints – often called “Mormons” – will hear an array of talks from religious leadership. But another speaker will likely be a member of the church’s auditing department, who, if he follows tradition, will state that the institution’s financial activities from the past year were “administered in accordance with Church-approved budgets, accounting practices, and policies.” No further specifics are typically provided.

This yearly ritual may seem striking in the face of the church’s February 2023 agreement to pay a US$5 million fine in a settlement with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. According to its press release, the SEC concluded that the church went to “great lengths” to “obscure” its investment portfolio. A church statement expressed “regret” that its leaders had followed faulty legal counsel and insisted that the fine would be paid through “investment returns” rather than members’ donations.

The settlement came on the heels of other controversies about the church’s taxes and financial portfolio, which journalists and whistleblowers have estimated at around $100 billion.

These revelations have raised questions concerning the ethics of a religious organization amassing such a large amount of wealth, and how it is balanced with charitable giving. But headlines often overlook the long and surprising history of the modern church’s financial success – as well as the continued anxiety surrounding its economic reserves.

Share and share alike

Mormonism was born through the spiritual quest of Joseph Smith, who was raised amid America’s Second Great Awakening during the early 1800s, a period of Christian revivals. His parents were religious seekers who struggled to find a fulfilling church, and tussled with the young country’s financial turbulence. Smith’s father had lost savings in an ill-fated ginseng deal, plunging the family into two decades of poverty.

It is no surprise, then, that when Smith formed his own church, its teachings included a sharp critique of the capitalist system. Early converts to what was originally called the Church of Christ, organized in 1830, were encouraged to consecrate all their goods to their new religious community so it could redistribute resources to those in need.

It was one of many communal experiments Americans attempted during the antebellum period as religious innovators offered alternatives to what they believed was a dangerous and uncaring economic system. Smith’s earliest revelations denounced individualism and urged believers to share their property and resources with one another.

Yet financial difficulties, personal clashes and other challenges doomed the experiment from the start. Within just a few years, the new church’s leaders had already abandoned the consecration ideal. In its stead, Smith directed members to donate “surplus property” to help pay off the group’s immediate debts and then to donate “one tenth of all their interests annually.” This commandment commenced a practice of tithing that still exists today, though it has been interpreted in different ways over the years.

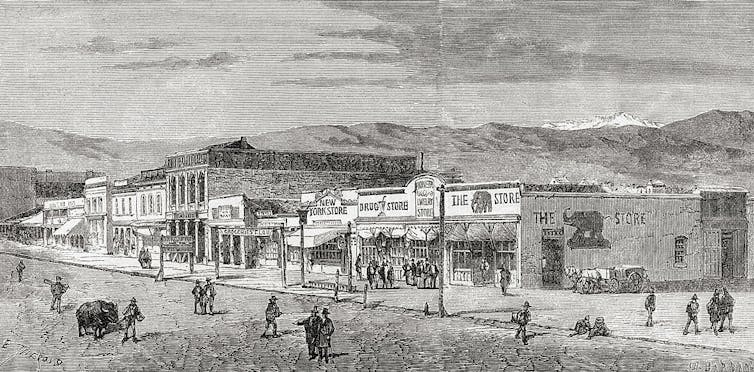

Hardscrabble years

Over the first two decades of the church’s existence, the Latter-day Saints had to relocate their headquarters multiple times – including seven years in Nauvoo, Illinois, a focus of my historical research. By the time the Saints reached Utah’s Great Salt Lake in 1847, leaders and members alike largely embraced the economic system that Smith had previously decried.

A series of national economic crises during the late 19th century further tested the church’s finances and financial ideals. In addition, the government’s decision to prosecute polygamists amid growing criticism of the church’s “plural marriages” crippled the region’s economy until Latter-day Saint leaders renounced the practice in 1890.

Facing financial ruin, the church’s prophet and president in 1899, Lorenzo Snow, urged members to redouble their commitment to tithing. The church formalized its expectation that members donate 10% of their annual income to remain in good standing. To this day, Latter-day Saints are expected to meet with local bishops every year and state that they have paid a full tithe.

By 1907, Snow’s successor, Joseph F. Smith, jubilantly announced that tithing income had paid off all the church’s loans. He even predicted that if the current rate continued, “we expect to see the day when we will not have to ask you for one dollar of donation for any purpose.”

Bust to boom

Donations only increased over the following decades, however, as the church continued to grow rapidly. The prosperity of the 1950s enabled an ambitious construction agenda for the next decade, as the church built over a thousand new meetinghouses and temples for its exploding membership.

Yet high spending, poor financial management and unwise or unlucky investments brought another financial crisis, and the church soon found itself cash-poor. By 1962, the budget had amassed a $32 million deficit. Leaders ceased offering detailed financial reports, which had been inconsistent yet common staples at the church’s General Conference.

Things started looking up the next year when N. Eldon Tanner, a successful Canadian politician and businessman, joined the church’s leadership and modernized its financial structure, investing any surplus. The church was once again on solid financial footing by the end of the 1960s, though it did not resume the release of detailed financial reports. Instead, Tanner empowered a private economic team to continue growing the faith’s portfolio.

Decades of membership growth, tithing donations and lucrative investments resulted in the modern church’s massive accumulation of wealth. This financial success has enabled it to oversee a worldwide church with nearly 17 million members of record, tens of thousands of employees and countless volunteer and charitable programs.

Its investments became so profitable in the early 2000s that, according to the SEC report, church leaders explored ways to shield their success from the public. According to one whistleblower, church authorities feared that greater transparency would discourage members from further tithing.

Giving to God

While the church reports giving over $1 billion in charitable aid last year, some members and observers alike critique leaders for not donating more, given the vast size of its investment portfolio, which is almost twice the size of Harvard’s endowment.

The issue also raises important ethical questions regarding a religious institution’s obligations toward its own members. Should Latter-day Saints, especially those who are struggling financially, still donate a tenth of their income to a church whose reserves are likely deep enough to pay off more than a decade of expenses? The seeming discrepancy between the transparency required of individual members and the church’s own lack of accountability has unsettled some members.

Yet many believers emphasize that their tithing’s purpose is not merely to add to the church’s coffers but to help build the kingdom of God – their donations are primarily offered for spiritual reasons, not worldly ones. And investments are also a safety net for the faith’s growth: Leaders likely hope it can support rapidly growing membership in lower-income countries.

As absurd as it may be to call a $100 billion dollar portfolio a “rainy day” fund, the church’s turbulent history may have led leaders to see it as just that.![]()

Benjamin Park, Associate Professor of History, Sam Houston State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.