Catastrophe overload? Read philosophers and poetry instead of headlines

Rachel Hadas, Rutgers University Newark

For almost two years now, Americans have been confronted daily by ominous tidings. We are living through stressful times. Reading the news feels awful; ignoring it doesn’t feel right either.

Psychologist Terri Apter recently wrote about the “phenomenon in human behavior sometimes described as ‘the hive switch,’ where "catastrophic events eliminate selfishness, conflict and competitiveness, rendering humans as co-operative as ultra-social bees.”

But if hurricanes, earthquakes or volcanoes trigger the hive switch, does this principle hold for man-made catastrophes?

What about the immigration policy that has been separating children from their parents? School shootings, suicides, ecological disaster?

What about the flood of frightening and infuriating news that splashes against us daily?

In response to all this, people are hardly swarming into a cooperative hive. On the contrary, our human qualities of imagination, alertness and compassion seem to be turning against us. To imagine the suffering of our fellow beings and the future of our beleaguered planet provokes rage, dread and an overwhelming sense of helplessness.

What, if anything, can we do?

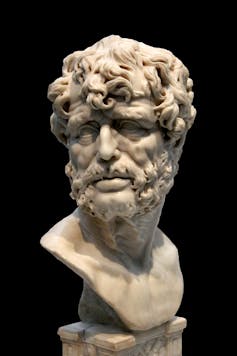

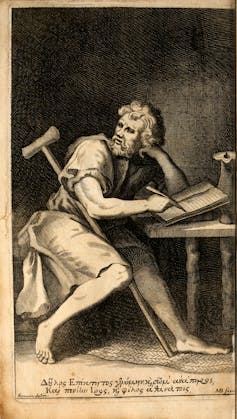

Listen to Seneca and Epictetus

Rage and dread can morph into political activism, but it’s hard not to feel that any change is too little and too late.

The children who have been separated from their parents, for example, even if they’re all reunited, which doesn’t seem likely, will bear the psychic scars for the rest of their lives, as physician Danielle Ofri has pointed out eloquently in Slate.

How should people react to rising suicide rates? Perhaps, judging from much recent coverage, the most we can hope to do is muster enough insight and hindsight to try to prevent the next one.

Yet this spring’s exhaustive coverage of a pair of celebrity suicides – Anthony Bourdain and Kate Spade – sent me back to the Stoic philosophers, thinkers who flourished, particularly in Rome, in the first and second centuries. Uninterested in abstruse speculations, these philosophers stressed ethics and virtue; they were concerned with how to live and how to die. Stoic psychology offered and still offers help working with the mind to calm our anxieties and help us to fulfill our function as human beings.

Both Bourdain and Spade, creative and successful personalities, icons of glamour and achievement – particularly Bourdain, whose restless and courageous explorations of various corners of the world inspired countless viewers and readers – turned out to have been vulnerable people.

William B. Irvine, whose 2009 “A Guide to the Good Life: The Ancient Art of Stoic Joy” I’ve been rereading, usefully distills from his four favorite Stoic writers, Seneca, Epictetus, Musonius Rufus and Marcus Aurelius, two salient Stoic techniques for combating dark thoughts. I’ll continue this teaching tradition by distilling Irvine.

The advice of writers like Seneca and Epictetus feels remarkably germane. The kinds of misery that are often mentioned in connection with suicidal impulses, such as fear and anxiety, are perennial components of the human condition. When we speak of a suicidal person wrestling with demons – a word as old as Homer – that’s what we’re talking about.

The Stoics teach that you can try to counter your demons – not with talk therapy, let alone pharmaceuticals, but by working with your mind.

Be ready

The first technique is negative visualization: Imagine the worst so as to be prepared for it.

Most likely the worst will never happen. The bad things that can and probably will happen are likely to be milder than the worst thing you can think of. You can feel both relieved that the worst hasn’t happened and also somewhat mentally bolstered against the worst possibility.

“He robs present ills of their power,” wrote Seneca, “who has perceived their coming beforehand.”

Elsewhere, Seneca writes, “Trees that have grown in a sunny vale are fragile. It is therefore to the advantage of good men, and it enables them to live without fear, to be on terms of intimacy with danger and to bear with serenity a fortune that is ill only to him who bears it ill.”

Much the same point is made by Edgar, disguised as Mad Tom, when he observes in “King Lear” that “the worst is not/So long as we can say ‘This is the worst.’” The very fact of being able to comment on how bad things are – and such bemoaning is now a daily ritual for many of us – means that we have survived.

Divide and conquer – or not

The second Stoic self-help technique is what Irvine calls the dichotomy of control: Divide situations into those you have some control over and those you have no control over.

Epictetus observes that “Of the things that exist, Zeus has put some in our control and some not in our control. Therefore…we must concern ourselves absolutely with the things that are under our control and entrust the things not in our control to the universe.”

Irvine adds a third category, thereby transforming the dichotomy into what he calls a trichotomy: things we have no control over, things we have complete control over and things we have some degree of control over.

We can’t control whether the sun rises tomorrow.

We can control whether we have a third bowl of ice cream, what sweater we choose to wear or whether to press SEND.

And, as for suicides, school shootings, agonized children torn from their parents? We can do something. We can vote, run for office, organize, contribute money or goods. In these ventures we can cooperate with our neighbors and colleagues, acting as hive-like as possible without being paralyzed by anguish.

Play baseball, go to the park

Those fortunate enough to experience private joy still sense the shadow of public dread. Yet joy is still joy; life still needs to be lived.

If we’re baseball players, we can play baseball. If we’re grandparents, we can take our grandchildren to the park. We can read – not only the news, but fiction and history that takes us out of our moment. And we can read poetry, which has the power of distilling our times, of making our moral dilemmas, if not precisely soluble, beautifully clear.

If we’re poets, we can write poetry – not a community venture, ordinarily, but what these days is ordinary? Public anguish makes its way into private lives, and some of the best new poetry braids public and private together. I myself both read and write poetry – both activities over which I have a good deal of control. And the poetry I’ve been reading is riveting.

An eloquent recent poem that encompasses the ethical dissonance between home and homelessness, safety and danger, is A.E. Stallings’s “Empathy.”

Interestingly, the Stoic notion of negative visualization animates the poem’s argument: how good that I and my family are snug in our beds at home and not tossing on a raft in the dark. It could be so much worse:

My love, I’m grateful tonight

Our listing bed isn’t a raft

Precariously adrift

As we dodge the coast-guard light…

And in its final stanza the poem unflinchingly rejects the easy notion of empathy as smug and superficial and hypocritical:

Empathy isn’t generous,

It’s selfish. It’s not being nice

To say I would pay any price

Not to be those who’d die to be us.

Rejecting what poet William Blake called “single vision,” Stallings courageously sees, and seems miraculously to write from, both sides.

She also manages to live on both sides. For the past year and a half, she has been doing extraordinary work with refugee women and children in Athens.

The dark undercurrents roiling in our time can also be felt in Anna Evans’s “Not My Son,” a villanelle whose rhymes of “border,” “order,” “disorder,” “ignored her,” “implored, her” and “toward her” clang with ominous music.

Poems like “Empathy” and “Not My Son” aren’t comfortable to read, nor were they, presumably, very comfortable to write. But they represent a measure of what some of us who happen to be poets can do; and I’d rather take in the frightening news as these poets thoughtfully and eloquently present it than gobble down headlines raw.

My next collection will be called “Love and Dread.” The Stoics knew that dread is always part of the picture.![]()

Rachel Hadas, Professor of English, Rutgers University Newark

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.