Curious Kids: What makes the wind?

Adam Sokol, University of Washington

Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to curiouskidsus@theconversation.com.

What makes the wind?

Wind has been whirling around the world since long before we’ve been here to notice it. It howls outside your window, toppling trees and stirring up storms that could snatch your hat right off of your head and send it flying through the air.

What makes the wind blow? And why hasn’t it stopped by now? Whether it’s a gentle breeze or a hurricane-strength gust, it’s all powered by the Sun. But how could the wind blowing down your street be driven by something so far away?

Blame it on the Sun

It takes only eight minutes for sunlight to travel from the Sun to the surface of the Earth. When it gets here, it warms things up. You experience this yourself when you sit outside under blue skies and feel the Sun’s warmth on your skin.

As the Earth’s surface warms, so does the air that touches it. And when air gets warm enough, it rises high into the sky. This is how hot air balloons fly: A small flame heats the air inside the balloon to lift it upwards.

When warm air rises, nearby air that’s cooler rushes in to fill the empty space left behind. The rushing air is what we call wind.

How does wind become dangerous?

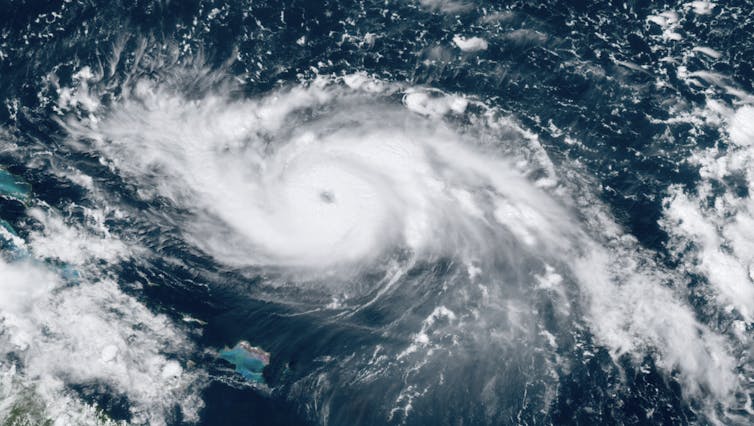

As it blows, the wind spins and spirals in different directions due to an invisible force called the Coriolis force. If the conditions are right, the Coriolis force wraps the wind into a giant, stormy spiral that is blown across the globe.

In the tropics, warm ocean waters provide an energy boost that strengthens the winds of a growing storm. If the wind speed reaches 74 miles per hour, about as fast as cars driving on a freeway, we call the storm a hurricane. A hurricane’s roaring winds and the floods that often accompany them can cause great destruction.

Strong winds can also be caused by sinking air. This happens frequently during thunderstorms. When the air below a thundercloud becomes very cold, it sinks down toward the ground, hits it and rushes away at fast speeds. This is why a warm summer day can suddenly cool off if a storm is nearby.

What in the world shapes the wind?

Wind is twisted and turned by the many obstacles it encounters along its way. In forests, trees block the wind and protect the forest floor from gusts. In big cities, towering skyscrapers funnel the wind into the narrow spaces between them, speeding it up.

Much larger obstacles, like oceans or mountain ranges, mold the wind into large, predictable patterns that shape weather and climate across the planet.

These patterns have shaped the course of history. Winds brought the rains that allowed ancient societies to grow food and prosper. Tropical breezes called the trade winds carried early explorers across vast oceans to new worlds.

Wind affects our lives in more ways than we often realize. Where I live, in Seattle, Washington, we depend on the wind to bring us rain from the Pacific Ocean. These rains support our farms, protect our forests from wildfires and keep our rivers filled with water. As water flows downstream and passes through huge hydroelectric dams, it generates electricity that keeps our homes warm and our lights on at night. Maybe the wind isn’t so bad after all.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you’re wondering, too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.![]()

Adam Sokol, Doctoral Student in Atmospheric Sciences, University of Washington

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.