Curious Kids: Why are some Beanie Babies worth more than others?

Christophe Spaenjers, University of Colorado Boulder

Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to curiouskidsus@theconversation.com.

Why are some Beanie Babies worth more than others? – Theo R., age 8, Rockford, Illinois

Most Beanie Babies are not worth much money. A new one at the store might be priced as low as US$5, depending on its size. If you buy a new Floppity the rabbit or Hissy the snake today and try to resell it tomorrow, you will likely lose money. That’s because Beanie Babies are made in large enough quantities that anyone who wants one can get one.

Still, every so often, a Beanie Baby resells for a lot of money. It’s not always easy to know when this happens, because many transactions are private, and not every for-sale listing leads to an actual purchase. Still, some Babies seem to have traded online for hundreds or even thousands of dollars in recent years. You might wonder why.

I study the prices of things people like to collect, such as paintings, diamonds and wine. The reason a particular Beanie Baby – or anything, really – can sell for a high price is because, when an item is attractive but rare or difficult to get, it becomes more valuable. Economists describe this situation as the demand being greater than the supply.

Beanie bubble

Beanie Babies were launched in 1993 by a toy company called Ty. In the late 1990s, some people went nuts for these plush toys. The craze started with collectors in the Chicago suburbs but quickly spread – helped by the rise of online auction websites such as eBay. Collecting Beanie Babies became a fad not just among kids who thought they were cute or wanted to play with them, but also among adults who thought the plushies offered a way to get rich quick.

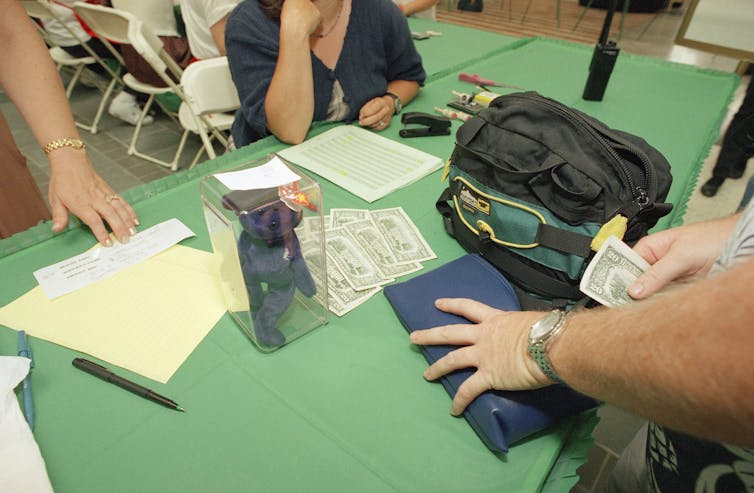

As more and more people started looking for certain Beanie Babies – especially those Ty had produced only in very limited quantities – resale prices went up. A bear given to Ty’s employees for Christmas quickly started selling for more than $5,000 on eBay.

Some buyers believed collecting Beanie Babies was a great way to make money. They bought at high prices, thinking they could resell at even higher prices.

Economists call this a bubble. A bubble is when a lot of enthusiastic people buy a particular thing at prices that far exceed its true value. It’s happened many times throughout history, with everything from companies to gold to artworks.

The hype about Beanie Babies started to cool down at the turn of the century, as collectors began to realize that many of the stuffed animals were not scarce after all. When people started to sell their collections, prices fell even further.

Rarity makes a Beanie worth more

Today, only a tiny fraction of Beanie Babies are worth something. Their value has nothing to do with how nice they look or how much fun they are to play with. Valuable Beanie Babies are simply the ones that are very rare.

For example, Ty sometimes made small batches of animals with slightly different materials. Ty also gradually changed the tag – the heart-shaped paper attached to the animal’s head with its name. The Babies with the oldest tags are typically more valuable. Occasionally, Ty goofed with the spelling on the tags. For example, Pinchers the lobster was for a short time labeled as “Punchers.”

To be worth money, rare Beanie Babies must also be in perfect condition. In fact, the most valuable animals have never been played with: they look brand-new, still have their tags and are stored in plastic cases.

This is similar for other collectibles. The most expensive bottles of wine or postage stamps are the ones that are old, rare and have never been opened or used. Rarity and condition are very important in determining the price of lots of collectibles, including Pokémon and Magic: The Gathering cards, as well as videocassettes and sports memorabilia.

Beanie Babies’ value is what people will pay

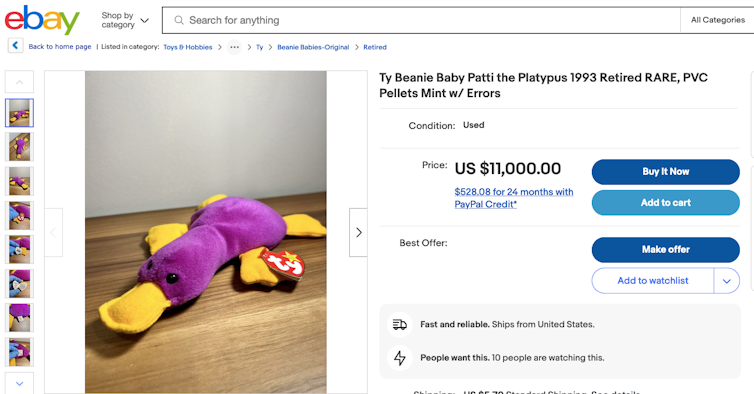

It’s a little hard to know what rare Beanie Babies are worth now, because every toy is different and prices vary widely.

Just because someone lists their Patti the platypus for $11,000 doesn’t mean a buyer will come forward to pay that amount for it. The best way to learn about the current value of something is to look at recent sales of items that are very similar.

Even if some Beanie Babies are worth a lot of money today, nobody knows if they will keep their value in the future. It’s possible a new toy will come along that people like better.

The truth is, prices of all collectibles fluctuate over time, as people’s tastes – and their beliefs about other people’s tastes – change. The value of anything is what other people are willing to pay for it.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you’re wondering, too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.![]()

Christophe Spaenjers, Associate Professor of Finance, University of Colorado Boulder

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.