Curious Kids: Why does grammar matter?

Laurie Ann Britt-Smith, College of the Holy Cross

Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to curiouskidsus@theconversation.com.

Why does grammar matter? – Maci, 13, Indianapolis, Indiana

After 20 years of teaching academic writing to both native speakers and English language learners, I can attest that at some point, just about everyone asks me why, or even whether, grammar matters.

There is more than one way to define grammar. Linguists – the people who study language – define “grammar” as a description of how a language operates. Though some people use it to bully people for making mistakes, grammar is not a way to decide if language is right or wrong. Everyone makes mistakes, and the English language is amazingly flexible in how its pieces can be put together and understood.

That’s because English is a “living” language, actively spoken by people worldwide. It grows and changes, picking up new words and new ways of constructing meaning all the time.

All kinds of factors influence the way people talk, including regional variations, age, ethnicity, education level and technology. People from Indianapolis use English differently than people from Alaska or Georgia. And American English sounds and works differently than the English spoken in England, Jamaica or India. But they are all still considered English.

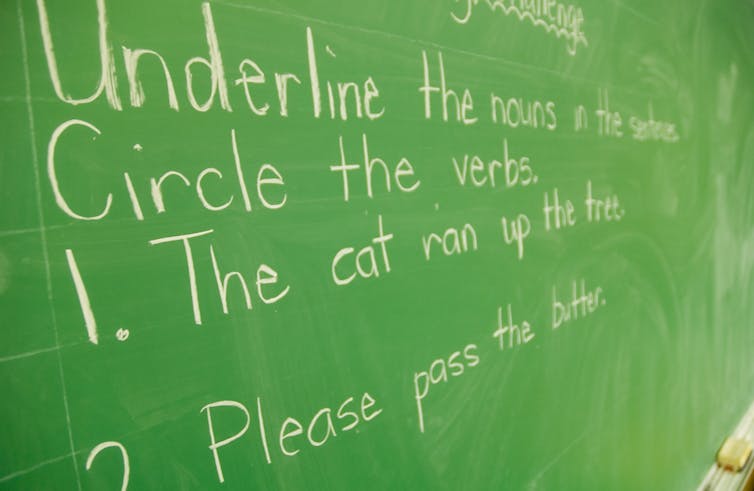

Through reading, writing and speaking, you have already learned quite a bit about how English works. You began your education in grammar when you first started using simple sentences. For example, my son had to learn to say “carry me,” not “carry you,” when he wanted to be picked up. That’s grammar, even though you didn’t always call it that.

The school subject we call grammar is the next step. It establishes some ground rules that attempt to define what can be considered a more uniform, established version of English. There is a complicated history of how those rules were created and who benefits from them. The end result is that schools teach the kind of English students in their country will be expected to use in public, at work and in formal writing.

Writing exists to be read. So the reader must be considered when you construct sentences. You write differently for your friends, your parents and your teacher. The grammar you learn in school helps you meet the expectations of the reader. They also learned a similar grammar in school.

Wait, did I just make a grammar mistake using “they” – plural – to refer to a singular “reader”?

Well, maybe not. Remember how I said English is a living language? The use of “their” as a singular, nongendered pronoun is one example of how the language is changing. Traditionally, I would have written “he,” because for so long male was the default gender. As the social thinking about gender changed, people began to write “he or she” to be more inclusive. Now we can use “they,” which is all-encompassing.

That shift will continue to be debated, as will starting a sentence with a conjunction like “but” or “and,” which used to be discouraged. But I think I get why these changes are happening: They mimic speech.

Studying grammar helps make communication between people clearer. Once you understand your own language and appreciate its patterns and varieties, you can more easily understand how other languages are constructed, making them easier to learn. Being able to understand across languages allows you to share your ideas and the ideas of others more broadly.

Grammar matters a lot – just maybe not for the reasons you thought.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you’re wondering, too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.![]()

Laurie Ann Britt-Smith, Director of the Center for Writing, College of the Holy Cross

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.