Innovative tech jobs needed to help rural America rebound

Click play to listen to an abbreviated version of this article.

(Texas News Service) When the pandemic upended life as we know it and changed how we work, it also sparked notable shifts in rural America, a vital part of our overall economy For one, the population in rural counties grew by one-quarter percent after a decade of either no or slow growth, as more people moved from urban centers during COVID-19.

An estimated 46 million people, or roughly 14%, of the U.S. population currently live in rural areas.

It took until mid-2023 for the rural workforce to almost fully recover from pandemic job losses. There are now 20.2 million workers with a 3.8% unemployment rate, according to the latest estimates provided by economists at the U.S. Department of Agriculture. It's still below 2019 pre-pandemic levels of 20.4 million rural workers.

Currently, the top employment industries in rural America are government, agriculture, manufacturing, health care, retail, and hospitality.

Feeling the Brunt of the Great Recession

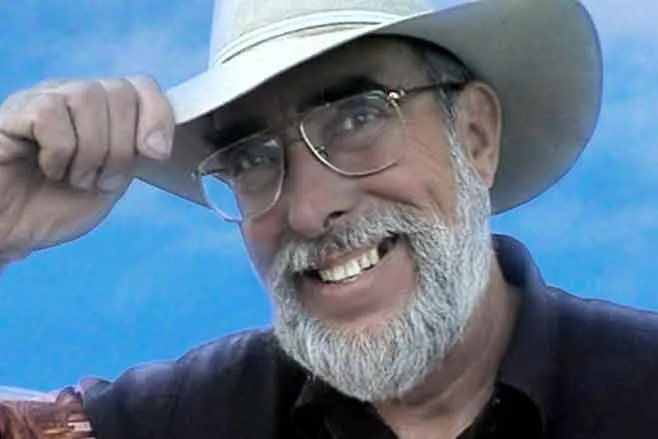

Employment in rural America actually began to slowly decline after the Great Recession, when it stood at 21 million. "Since the 2008 recession, there has been a massive divide between urban and rural areas on just about every front. If you dig into the data, it's because of the winners and losers of the tech and innovation economy," says Matt Dunne, founder and executive director of the Center on Rural Innovation.

He explains: "Urban places were able to benefit from tech innovation and the centers of that innovation and investment being in cities. Rural places not only did not see that kind of economic activity, the traditional rural industries - manufacturing, agriculture, extraction - saw automation eliminate jobs and also facilitate the transfer of those jobs to other markets in other parts of the world."

COVID-19 also exposed the stark digital divide as millions in rural areas were prevented from going to school or work online during shutdowns because of the lack of access to broadband.

© iStock - arcoss

The Center on Rural Innovation, founded by Dunne in 2017, is a nonprofit with a mission to build tech economies in rural places through tech startups and creating innovation-based jobs.

"Our North Star is associated with the fact that rural America represents about 12% of our nation's workforce, but only 5% of computer and math jobs. We believe if we are going to get back to just an equilibrium in terms of economic mobility and resilience in the face of further automation, we need to get that 5% up to 12%," adds Dunne.

To spur growth of tech hubs, the federal government is pumping billions into the national economy with the bipartisan 2022 CHIPS and Science Act to boost production of semiconductors in the U.S. which can benefit rural areas. The federal government also has ratcheted up efforts to provide high-speed reliable internet service for all.

Money is also being invested in infrastructure to create jobs with targeted projects for rural areas. Clean energy jobs, for example, make up 1% of the rural workforce amounting to 243,000 jobs in wind, solar and biofuels.

One of the latest investments in rural communities includes $5 billion dollars in spending to foster economic development with investments in everything from infrastructure to "climate-smart" agricultural practices for farmers. The goal is to create opportunities in rural America so people don't need to leave to find good-paying jobs.

Investing in the Worker Where They Live

Preparing the rural workforce for quality, family-sustaining jobs in their communities is one of the core priorities of the U.S. Department of Labor's Employment Training Administration, according to Manny Lamarre, senior policy advisor of workforce development at the DOL.

"We set our priorities in terms of key sectors, including advanced manufacturing, construction, health care, education, and IT. But we recognize that there's a variety of variances in local communities in terms of specific jobs."

Lamarre points to the Workforce Opportunity for Rural Communities (WORC) grants which specifically fund workforce training in Appalachian, Lower Mississippi Delta, and Northern Border regions and are created "in collaboration with community partners and aligned with existing economic and workforce development plans and strategies."

WORC grants are based on three criteria, he explains. "How are grantees addressing historic inequities? Are they creating career pathways or pathways into good jobs and economic mobility? That's the piece around the job training. That's the piece around convening industry and partners to create career pathway programs. And then third is high-quality employment outcomes for workers. That's the straightforward of now getting into that job."

Lamarre continues, "Since 2019, we've made five rounds of investments and we've awarded over 120 grants totaling over a $166 million dollars, and the grants range from about $150,000 to $1.5 million. They are being used for on-the-job training, sector strategies, apprenticeship opportunities, and also supportive services.

"There are existing high-quality jobs and we also know from the historic investments including the bipartisan infrastructure bill, the Chips and Science Act, and the Inflation Reduction Act for clean energy jobs that there are additional opportunities that are coming down the pipelines as well.

"We want rural communities to be ready to engage and positioned for those opportunities. It's all under the umbrella of ensuring that people can live and work in the communities that they are from and the communities that they represent, particularly for our rural residents," he tells me.

Demographic Challenges

That push to keep working-age people from leaving rural areas speaks to demographic challenges.

"A lot of people leave. They leave to go to college. There is a lifecycle to this thing," explains Mark White, clinical associate professor at the Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign.

"They find work somewhere else because that's often where the work that fits them is available. Or there is a density of jobs there, so if one job doesn't work out they can go to another one as opposed to there's only one job there for them. Sometimes people move back (to rural areas) in their 30s - if they want to come back - to start families."

White also says there are fewer young people in rural America because Generation Z is smaller than the millennial generation. The population is also aging, with 20% aged 65 years or older, compared to 16% in metro areas.

With an aging population and younger people leaving, White agrees it heightens the urgency to invest in workforce training locally and also making young people aware of jobs that do exist.

"There are jobs in agriculture, construction, and health care everywhere. I think what a lot of communities need to think about is: how do we connect our young people to those jobs that are locally available? Some places have made investments in career technical education and they also recognize there's a need to connect employers and students at an earlier age," adds White.

As an example, White points to Missouri's investments in apprenticeships in 2019. The state now boasts that Apprenticeship Missouri ranks second in the nation for new apprenticeships and third in the country for completed apprenticeships that includes fields such as cybersecurity, advanced manufacturing, and health care.

The health care industry has needs across the board in rural areas around the country.

One long-standing program showing success in recruiting doctors is The Thomas Jefferson University Physician Shortage Area Program in Pennsylvania.

It recruits and trains medical schools from rural areas and small towns who want to practice in similar areas after completing a residency program. The program says it's trained more than 300 students in the program with a nearly 80% retention rate - graduates staying in or returning to rural or small town populations.

A growing number of community colleges in rural areas, such as Northland Pioneer College in Arizona, are offering bachelor's degrees after passage of a 2021 state law designed to better meet their workforce needs. Arizona is among roughly two dozen states now allowing community colleges to offer four-year degrees.

The Rural Innovation Network

The Center on Rural Innovation has established the Rural Innovation Network which counts 38 communities in 24 states aiming to develop tech economies and create jobs.

Dunne says the organization is conducting pilot programs in job training for roles that include web developers, cybersecurity, and data analytics. They are in early stages and too early to scale. He stresses, though, that one key thing he's doing is hearing from employers in rural areas about their demands, so skills training matches needs.

One big hurdle he says he faces is debunking myths he encounters that innovation can't be found in rural areas. He stresses that while federal investments are targeting manufacturing in rural areas, he does not want these same communities to be passed over when it comes to investing in research and development.

"It's in our national interests in terms of competitiveness that we are engaging all the competitive minds in terms of talent in our country, not just ones who happen to live in cities," stresses Dunne.

He adds: "I just think we're at a really interesting moment in our country. There's been an unprecedented amount of investment in what we think are the right things and now we just need to make sure that everyone remembers your zip code is not a determinant of your capacity or ability,"

Ramona Schindelheim wrote this article for WorkingNation.

Support for this reporting was provided by Lumina Foundation.