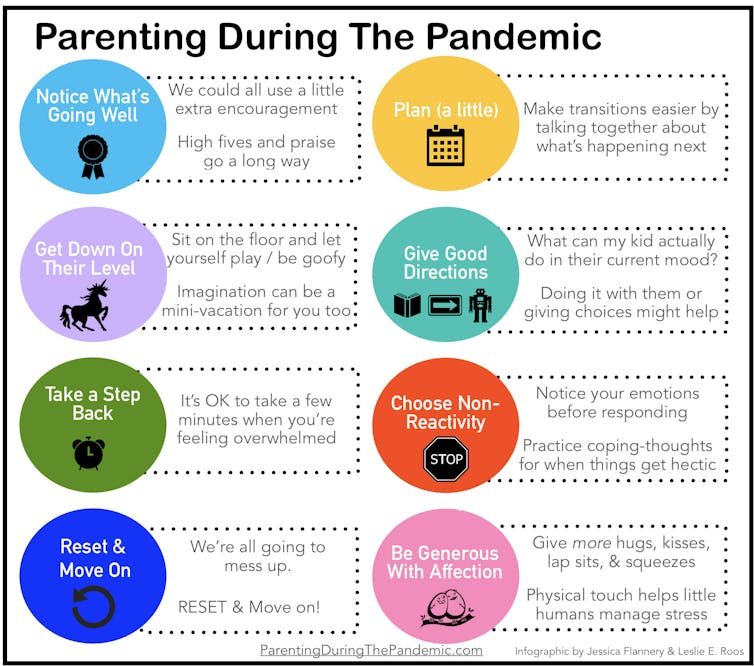

Try these 8 tips to reduce parenting stress during the coronavirus pandemic

Leslie E. Roos, University of Manitoba and Jessica Flannery, University of Oregon

Parenting can be tough at the best of times, but family life has changed dramatically during social isolation that’s been mandated by COVID-19. The good news is that children thrive in an incredible variety of settings. Emerging evidence suggests that a little stress, particular in the context of a supportive parent-child relationship, can actually be beneficial because it builds resilience when taking on future challenges.

As clinical psychology scholars, our research looks at how parent-child relationships can promote healthy development, particularly in the context of stress.

Here are a few research-based strategies to make this unprecedented time more enjoyable.

1. Notice what’s going well

Living in close quarters, it’s easy to pay attention to all the things going wrong, which can make children more resistant to helping out. Praising your kids and letting them know you appreciate their effort pays overtime by promoting more positive behaviour and enriching your relationships.

You have permission to praise anything that you want to see more of. “Thanks for saying please when you asked for (your third) snack,” or “Nice job sitting so calmly!”

2. Plan (a little)

Children benefit from being able to predict small things and having some control. If you’re into making a daily schedule — great — but it might work just as well to chat about choices for upcoming activities a couple times each day.

If a task needs to happen, like schoolwork or cleaning, try sandwiching it between child-chosen activities. Research suggest that child choices can increase pro-social behaviour. Look for patterns and use that to your advantage by setting up extra incentives to prevent problems.

3. Get down to their level

Getting in multiple chunks of high-quality playtime throughout the day can help kids manage their emotions and behaviour, build cognitive skills and support parent-child bonds.

It’s easier to participate when you are sitting on the floor and can give play your full attention. If you’re having a hard time being distracted, try being over-the-top with silly voices, jumping jacks or getting messy. Imaginative play can be a welcome escape for adults too.

4. Give good directions

When you need something done, it’s wonderful to only ask once. Increase the likelihood of this by giving good directions: get close to your kids and make eye contact first. Ask them to do a specific, time-limited task, with no more than two or three steps, depending on child ability. “I need to you put away this game then come to dinner.” Wait there and count to 20 to make sure you receive a response. If not, try “Dylan, can I get an OK to cleaning up the game? It’s dinner time.”

Make sure the demand is realistic given their mood and energy. Using a “when-then” statement can be a powerful way to maintain control. “Dylan, when you clean up the game then you can choose an ice cream for dessert.” If that sounds too much like a sugary bribe, offer a family movie or playing with Super Soakers.

5. Take a step back

Pay attention to what your body feels like or your thoughts sound like right before you react. If you can step away from an escalating situation, chances are you’ll have a more pleasant day.

Identify what you might do to take a break — hand off parenting to a partner if possible, splash cold water on your face or take in a breath of fresh air. Even five deep breaths and reminding yourself about your love for your kiddo can provide the space you need to tackle the situation with a clear(er) mind.

6. Choose not to react (when you can)

Sometimes planned ignoring of a minor challenging behaviour is the most effective way to move through the day. Another option is to describe what you’re seeing and offer some choices.

“Wow, you have a lot of energy and just kicked the door.… Can you show me your 20 best clucking chicken moves?” Saying the unexpected can move kids into playful compliance.

If exhaustion is making this hard, try a grandparent-approved adage: “Add water or fresh air.” This can include ice cubes, baths, coloured water, a walk around the block or even spotting birds or dog poop piles from an open window.

7. Reset and move on (when you can’t)

Unpleasant outbursts or harsh words can happen to everyone. It’s sometimes helpful for parents to offer a brief apology and gently move into new activities.

It’s equally important not to force an apology from your child, which can have the unintended consequence of making things worse. When you’re in this “resetting” mode, try think back on the points above — getting down to their level, being goofy or noticing small positives will make it easier to move on with your day.

8. Be generous with affection

Across species, physical comfort is a powerful way to manage stressful events. As much as your sheer quantity of family time might not make extra squeezes or hand-holding automatically appealing, that’s often exactly what kids need to manage big emotions that are simmering under the surface.

We hope this list provides some assurance that you can offer your kids exactly what they need to feel loved, safe, and supported. If you’re reading this, chances are that you’re already providing just that.

If you’d like to share your experiences during the pandemic, we are researching how parents of children 0–8 years old are managing and what else they need at ParentingDuringThePandemic.com. Our ultimate goal is to develop resources for our communities to better meet family needs.![]()

Leslie E. Roos, Assistant Professor, Department of Psychology, University of Manitoba and Jessica Flannery, Doctoral Candidate in Clinical Psychology, University of Oregon

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.