When does clinical depression become an emergency?

John B. Williamson, University of Florida

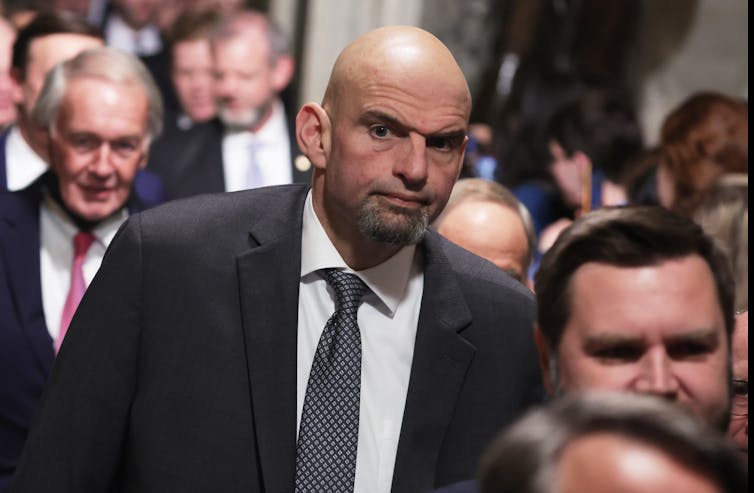

The news that Sen. John Fetterman, a Pennsylvania Democrat, checked himself into Walter Reed National Military Medical Center on Feb. 15, 2023, to be treated for clinical depression sparked a national discussion around the need for openness about mental health struggles. This comes after Fetterman suffered a near-fatal stroke in May 2022, prompting questions about possible links between post-stroke recovery and mental health.

The Conversation asked John B. Williamson, an associate professor of psychiatry and neuroscience at the University of Florida, to explain when depression becomes a crisis and what inpatient treatment entails.

What is clinical depression?

Clinical depression, or major depressive disorder, occurs in 20% of the population over the lifetime. It can surface and differ from person to person in a variety of ways.

Clinical depression symptoms include feelings of sadness and loss of interest and motivation to engage in once pleasurable activities such as hobbies. Other symptoms include changes in appetite – either increased or decreased – changes in sleep patterns, be it too much or too little, loss of energy, restlessness and difficulty thinking and concentrating. To qualify as clinical depression, these symptoms must persist for at least two weeks.

One form of the condition can also occur in the context of stressful situations, such as the death of a loved one, divorce or loss of a job. Depressive symptoms can also occur alongside and because of other disorders and medical conditions like stroke and thyroid disease, and these conditions may complicate recovery.

Severe depression can mimic other conditions, including dementia, in which an impairment in thinking is significant enough to interfere with a person’s ability to live independently. It can also worsen the quality of life in older age. Depression has also been linked with higher rates of death from any cause, such as cardiovascular disease.

Untreated depression can negatively affect overall health and quality of life.

When does depression become an emergency?

An acute change in mood that persists for weeks or is associated with thoughts of self-harm should not be ignored. In some cases, it may constitute an emergency.

Depressed mood, whether from a major depressive episode, or in the context of another problem, can become an emergency when there are thoughts of suicide. Suicidal thoughts may be passive, such as preferring not to be alive, or active, meaning an explicit desire to harm oneself. Broadly, this means having ideas about ending one’s life.

It is important to understand the signs and risks for suicide to help prevent it, both for yourself and others. Feelings of hopelessness, agitation and lack of reasons to live are vulnerabilities for suicide. This vulnerability increases with poor sleep and higher risk-taking behavior, including substance abuse. Additional noticeable signs may be withdrawing from friends and family and increased preoccupation with death.

If a person expresses suicidal thoughts or a desire to harm or kill themselves, immediate attention is needed. Help is available through the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline and any emergency room.

What is inpatient care for depression?

Inpatient mental health care is useful when a more controlled environment is needed. This environment is important for patients at increased risk for suicide and can also be a useful tool for treating substance abuse, hallucinations and paranoia or mania in the context of bipolar disorder.

An inpatient care unit is meant to be a calm environment with 24/7 monitored care. Services include evaluation by professionals and may involve medication management when necessary. Inpatient care settings will usually offer individual and group psychotherapy options, as well as art therapy and other expressive therapies such as writing. And they may include education on the management of mental health.

The primary goal is stabilizing the patient, helping them to develop coping skills and connecting the patient with services to prevent future need for inpatient care.

The average stay in an inpatient unit is about 10 days. It is possible to enter inpatient care voluntarily. Others are admitted by a physician or other authorized individual, which in most cases would be a parent, spouse or adult child. Admission sometimes occurs by way of an emergency room visit or through communication with a health care professional. For instance, sometimes a therapist or physician may facilitate inpatient admission.

Is treatment for depression effective?

The good news is that depression responds well to treatment. In cases in which thoughts of suicide with imminent risk of harm are not present, depression can be managed with psychotherapy, medication or a combination of both. There is a great deal of evidence for the effectiveness of these approaches.

Clinical depression may go into remission with psychotherapy or the use of medication. Unfortunately, about half of people who experience clinical depression experience chronic or recurring symptoms. Longer-term treatment and self-care including psychotherapy and medication may be necessary.

There are additional treatment considerations when active thoughts of suicide are involved. It is important to discuss these feelings with a medical professional. Primary care physicians commonly treat depression via medication; slightly more than 13% of Americans take them. However, it may be beneficial to seek out treatment from mental health care specialists such as psychiatrists, psychologists, psychiatric nurses and other licensed mental health care professionals.

A conversation with either a primary care or a mental health care professional is a viable route to getting started with assessment and treatment. People who get treatment for suicidal thoughts are much less likely to kill themselves.

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration operates a national helpline to assist in facilitating appropriate treatment referrals for patients (1-800-662-HELP).![]()

John B. Williamson, Associate Professor of Psychiatry and Neuroscience, University of Florida

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.