Bird flu outbreak underscores need for early detection to prevent the next big pandemic

Treana Mayer, Colorado State University

The current epidemic of avian influenza has killed over 58 million birds in the U.S. as of February 2023. Following on the heels of the COVID-19 pandemic, large outbreaks of viruses like bird flu raise the specter of another disease jumping from animals into humans. This process is called spillover.

I’m a veterinarian and a researcher who studies how diseases spread between animals and people. I was on the Colorado State University veterinary diagnostic team that helped detect some of the earliest cases of H5N1 avian influenza in U.S. birds in 2022. As this year’s outbreak of bird flu grows, people are understandably worried about spillover.

Given that the next potential pandemic will likely originate from animals, it’s important to understand how and why spillover occurs – and what can be done to stop it.

How spillover works

Spillover involves any type of disease-causing pathogen, be it a virus, parasite or bacteria, jumping into humans. The pathogen can be something never before seen in people, such as a new Ebola virus carried by bats, or it could be something well known and recurring, like Salmonella from farm animals.

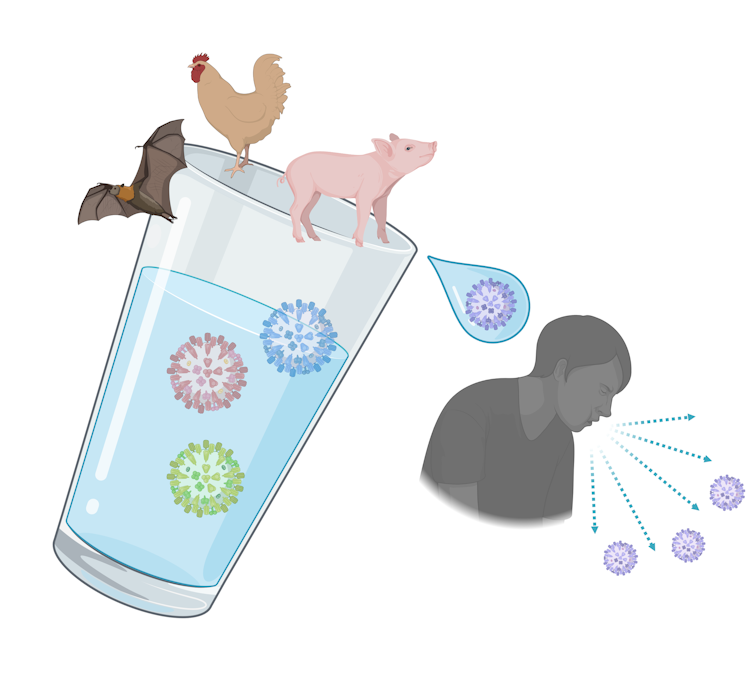

The term spillover evokes images of a container of liquid overflowing, and this image is a great metaphor for how the process works.

Imagine water being poured into a cup. If the water level keeps increasing, the water will flow over the rim, and anything nearby could get splashed. In viral spillover, the cup is an animal population, the water is a zoonotic disease capable of spreading from an animal to a person, and humans are the ones standing in the splash zone.

The probability that a spillover will occur depends on many biological and social factors, including the rate and severity of animal infections, environmental pressure on the disease to evolve and the amount of close contact between infected animals and people.

Why spillover matters

While not all animal viruses or other pathogens are capable of spilling over into people, up to three-quarters of all new human infectious diseases have originated from animals. There’s a good chance the next big pandemic risk will arise from spillover, and the more that’s known about how spillovers occur, the better chance there is at preventing it.

Most spillover research today is focused on learning about and preventing viruses – including coronaviruses, like the one that causes COVID-19 and certain viral lineages of avian influenza – from jumping into humans. These viruses mutate very quickly, and random changes in their genetic code could eventually allow them to infect humans.

Spillover events can be hard to detect, flying under the radar without leading to bigger outbreaks. Sometimes a virus that transfers from animals to humans poses no risk to people if the virus is not well adapted to human biology. But the more often this jump occurs, the higher the chances a dangerous pathogen will adapt and take off.

Spillover is becoming more likely

Epidemiologists are projecting that the risk of spillover from wildlife into humans will increase in coming years, in large part because of the destruction of nature and encroachment of humans into previously wild places.

Because of habitat loss, climate change and changes in land use, humanity is collectively jostling the table that is holding up that cup of water. With less stability, spillover becomes more likely as animals are stressed, crowded and on the move.

As development expands into new habitats, wild animals come into closer contact with people – and, importantly, the food supply. The mixing of wildlife and farm animals greatly amplifies the risk that a disease will jump species and spread like wildfire among farm animals. Poultry across the U.S. are experiencing this now, thanks to a new form of avian flu that experts think spread to chicken farms mostly through migrating ducks.

Current risk from bird flu

The new avian influenza virus is a distant descendant of the original H5N1 strain that has caused human epidemics of bird flu in the past. Health officials are detecting cases of this new flu virus jumping from birds to other mammals – like foxes, skunks and bears.

On Feb. 23, 2023, news outlets began reporting a few confirmed infections of people in Cambodia, including one infection leading to the death of an 11-year-old girl. While this new strain of bird flu can infect people in rare situations, it isn’t very good at doing so, because it is not able to bind to cells in human respiratory tracts very effectively. For now, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention thinks there is low risk to the general public.

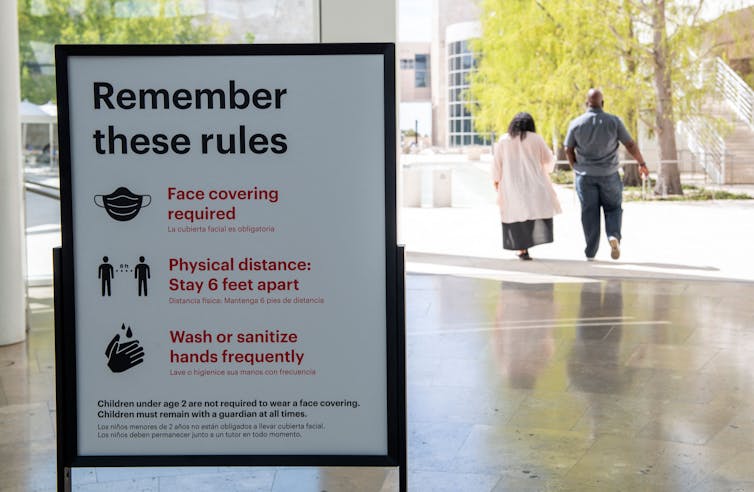

Active monitoring of wild animals, farm animals and humans will allow health officials to detect the first sign of spillover and help prevent a small viral splash from turning into a large outbreak. Moving forward, researchers and policymakers can take steps to prevent spillover events by preserving nature, keeping wildlife wild and separate from livestock and improving early detection of novel infections in people and animals.![]()

Treana Mayer, Postdoctoral Fellow in Microbiology, Colorado State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.