Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to curiouskidsus@theconversation.com.

Could we use volcanoes to make electricity? – Lawrence, age 7, Dublin, California

Turning red-hot lava from an active volcano into electricity would be dangerous and unreliable. Volcanoes don’t erupt on predictable schedules, and lava cools too quickly. But many countries, including the U.S., have found ways to tap volcanic heat to make electricity.

Geothermal energy comes from heat generated by natural processes deep within the Earth. In most areas, this heat only warms rocks and underground water near the surface. In volcanically active regions, however, the heat is much more intense. Sometimes it melts rock, forming magma.

Volcanoes act like giant heat vents, raising magma closer to Earth’s surface. Some of this molten rock may erupt, but much of it remains underground, heating the surrounding rocks and water. Where heated water rises to the surface, it creates hot springs and geysers that can last for thousands of years.

To harness this energy to generate electricity, engineers identify areas where magma is near the surface and drill deep wells down to the heated rocks and water. These wells bring steam to the surface, where it is directed into a power plant to spin turbines and generate electricity.

After it produces electricity, the steam cools and condenses back into hot water. The water may be used to convert a different liquid with a much lower boiling point, such as butane, to drive a second generator. Then it is pumped back underground to be reheated.

The Earth constantly produces heat, so geothermal energy is a renewable resource. And geothermal power plants produce much less pollution, waste and greenhouse gas emissions that warm Earth’s climate than burning coal, gas, oil or using nuclear energy.

Geothermal energy sources can last for decades or even longer. Unlike other renewable sources such as solar and wind power, geothermal energy is available 24/7, 365 days a year.

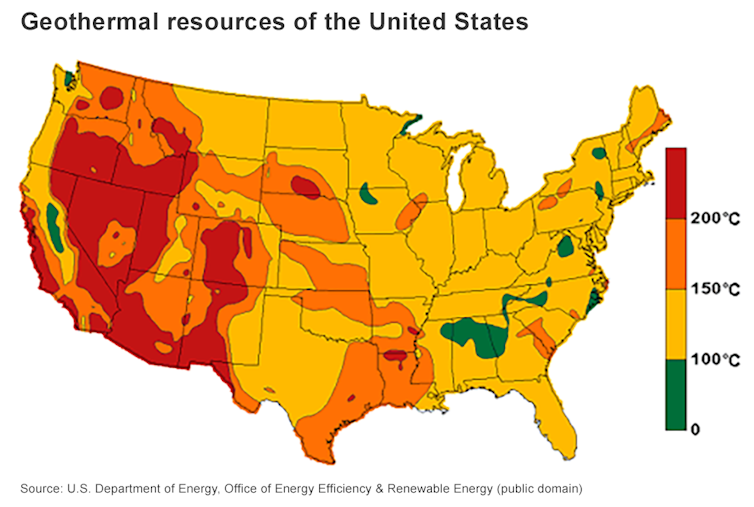

The world’s geothermal hot spots

Geothermal energy is already used in many places around the world, especially in regions with a lot of volcanic activity. For example, almost all of Iceland’s electricity comes from renewable sources, with geothermal energy supplying about 25%. The country sits on top of many active volcanoes, making it a perfect place for geothermal power plants.

Some U.S. states, including California and Nevada, have geothermal power plants, thanks to their volcanic regions. Other active geothermal sites, such as Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming, are protected from development.

Challenges for geothermal power

Why isn’t geothermal energy used as widely as wind or solar power? First, geothermal power plants need to be near volcanoes or other places where it is unusually hot beneath the surface. These resources aren’t always near large cities or industries that use a lot of electricity.

Second, drilling deep wells and building power plants can be expensive. However, the long-term benefits of geothermal power often outweigh the initial costs.

Third, in some cases, drilling and pumping water under pressure can cause small earthquakes. Scientists and engineers are working to predict and manage this effect.

Despite these challenges, tapping into the Earth’s natural heat can create a renewable, reliable and clean source of energy. As technology improves, more places around the world will turn to geothermal energy to light up people’s lives. Volcanoes are reminders of a great powerhouse deep underground that’s waiting to be harnessed.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you’re wondering, too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.![]()

David Kitchen, Associate Professor of Geology, University of Richmond

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.