Curious Kids: How do my eyes adjust to the dark and how long does it take?

Mark D. Fairchild, Rochester Institute of Technology

Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to curiouskidsus@theconversation.com.

How long does it take for your eyes to adjust to the dark and how does it happen? – Ellen T., 8, Cambridge, Massachusetts

No one can see in total darkness. Fortunately, there’s almost always some light available. Even if it’s only dim starlight, that’s enough for your eyes to detect. What’s truly amazing is how little light is required for you to see.

Human eyes have two main features that help us see better in low light: the pupil’s ability to change size, and the eye’s two types of light-sensing cells.

Opening up to let in more light

Your pupils are the black areas at the front of your eyes that let light enter. They look black because the light that reaches them is absorbed inside the eyeball. It’s then converted by your brain into your perceptions of the world.

You’ve probably noticed that pupils can change size in response to light. Outside on a bright sunny day, your pupils become very small. This lets less light into the eye since there’s plenty available.

When you move to a dark place, your pupils open up to become as large as possible. This expansion allows your eye to collect more of whatever light there is.

But from its tiniest size to its most wide open, your pupil can enlarge its area by a factor of only about 16 times. You can see well across changes in light level of far more than a million times. So there has to be something else going on.

Switching to different light sensors

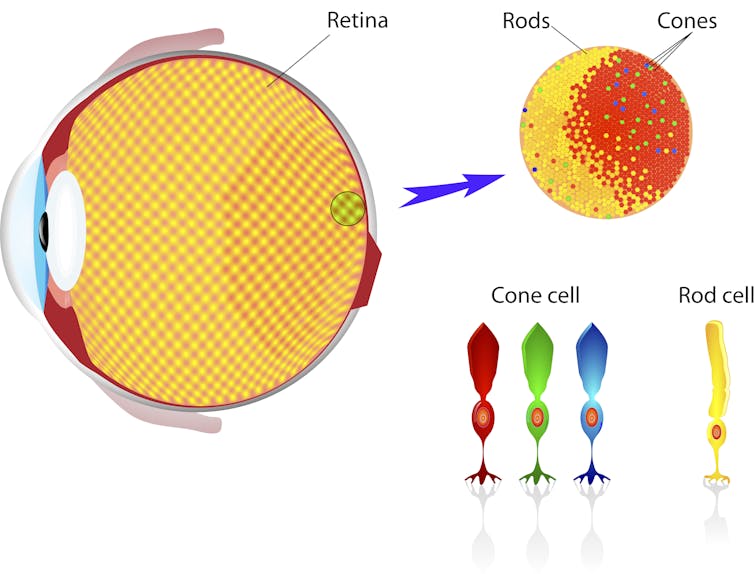

That’s where the photorecepters come in. These are the light-sensing cells that line your retina, the back part of your eyeball. The two kinds of photorecepters are called cones and rods, named because of their shapes.

Cones work when there is plenty of light. They’re able to respond to different colors of light, providing color vision. They also allow you to see fine detail and do things like read when the light is bright enough.

Rods, on the other hand, are far more sensitive to light and incapable of discriminating colors. They also pool their responses together when needed – that makes you more sensitive to light, but also means you’re less able to see fine details. That’s why you can’t read a book in the dark, though you might see its rectangular shape.

As you move from a brightly lit area to a dark one, your eyes automatically change from using the cones to using the rods and you become far more sensitive to light. You can see in the dark, or at least in very low light.

Just how long does it take?

When you’re in bright light, your rods are completely overwhelmed and don’t work. If you flip off the lights, your pupil will immediately open up. Your photorecepters start to improve their sensitivity, to soak up whatever light they can in the new dim conditions.

The cones do this quickly – after about five minutes, their sensitivity maxes out. After about 10 minutes in a darker place, your rods finally catch up and take over. You’ll start to see much better. After about 20 minutes, your rods will be doing their best and you will see as well as possible “in the dark.”

Try it. Find a very dark place, maybe your bedroom at night. Turn on whatever light you have and gather some colorful objects. Spend some time noticing how colorful, sharp and full of contrast things look.

Then turn off the lights and watch how the appearance of your room and objects changes over time. First it will seem very dark; then you will rapidly see better, thanks to your pupils and cones doing their jobs. Then, if it is dark enough, you will notice another rather sudden improvement after about 10 minutes, when the rods start to show their stuff. This is called dark adaptation.

What about total darkness? If you can find a place with absolutely no light, perhaps a closet, bathroom or basement, you can try the experiment again. This time, even after 20 minutes you won’t see any objects in the room. But you won’t see total blackness either. Try it and observe what happens.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com.

Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.![]()

Mark D. Fairchild, Professor of Color Science, Rochester Institute of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.