Earthquake in Turkey and Syria: how satellites can help rescue efforts

© iStock - allanswart

Emilie Bronner, Centre national d’études spatiales (CNES)

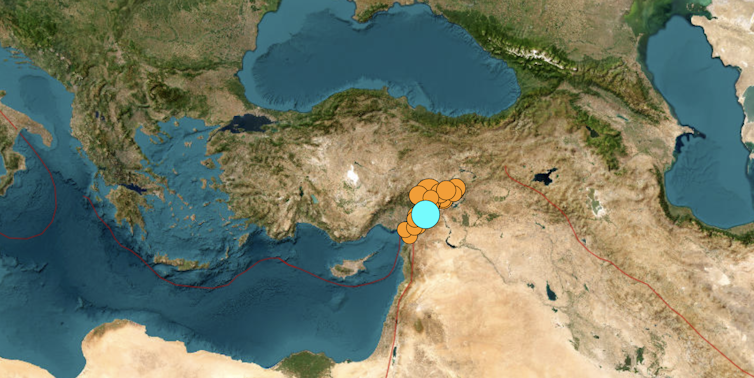

In disasters like the 7.8 magnitude earthquake and 7.5-magnitude aftershock that struck Syria and Turkey on February 6, 2023, international cooperation on satellite imaging plays a crucial role in the rescue and recovery efforts.

Such data enables humanitarian aid to better deliver water and food by mapping the condition of roads, bridges, buildings, and – most crucially – identifying populations trying to escape potential aftershocks by gathering in stadiums or other open spaces.

To quickly turn the eyes of satellites toward the affected areas, the Turkish Disaster and Emergency Management Authority (AFAD) requested the activation of the international charter on “Space and Major Disasters” at 7:04 a.m. local time. The United Nations did so for Syria at 11:29 local time.

In the meantime, 11 space agencies got ready to operate the most appropriate optical and radar satellites. For France, these are the optical satellites Spot, Pléaides and Pléiades Neo (medium, high and very high resolution), which will provide the first images as they pass over the area. Radar satellites will complement the optical information, as they also operate at night and through clouds, and can image landslides and even very small changes in altitude.

Every year, millions of people around the world are affected by disasters, whether natural (cyclone, tornado, typhoon, earthquake, landslide, volcanic eruption, tsunami, flood, forest fire, etc.) or man-made (oil pollution, industrial explosions, and more). Unfortunately, the intensity and frequency of these disasters are increasing with climate change, creating more and more victims, damaged homes, and devastated landscapes.

Anatomy of a disaster

The international charter on “Space and Major Disasters” defines a disaster as a large-scale, sudden, unique and uncontrolled event, resulting in loss of life or damage to property and the environment, and requiring urgent action to acquire and provide data.

The charter was created by the National Space Research Centre and the European Space Agency in 1999, soon joined by the Canadian Space Agency. Today, 17 member space agencies have joined forces to provide free satellite imagery as quickly as possible over the disaster area. Since 2000, the charter has been activated 797 times in more than 154 countries. It has since been complemented by similar initiatives from Europe (Copernicus Emergency) and Asia (Sentinel Asia).

Almost three quarters of the activations of the charter are due to weather phenomena: storms, hurricanes and especially floods, which alone account for half of the activations. In these sometimes unforeseen crisis situations, when the ground is damaged or flooded and roads are impassable, land-based resources are not always able to analyse the extent of the disaster and organise relief and humanitarian aid in the best possible way. By capturing the situation from space, with very high resolution, satellites provide crucial information quickly.

In some cases, the charter cannot be activated. This can be because the subject matter is outside the scope of the charter (wars and armed conflicts) or because space imagery is sometimes of little interest (in the case of heat waves and epidemics), or because the phenomenon evolves slowly and over a long time span (droughts).

Satellite data in response to crises around the world

As soon as a disaster occurs, satellites are programmed to quickly acquire images over the affected areas. More than 60 satellites, optical or radar, can be mobilised at any given time.

Depending on the type of disaster, different satellites will be mobilised, based on pre-established crisis plans – among them: TerraSAR-X/Tandem-X, QuickBird-2, Radarsat, Landsat-7/8, SPOT, Pleiades, Sentinel-2 among others.

Optical images are similar to photos seen from space, but radar images can be more difficult to interpret by non-experts. So following the disaster, satellite information is reworked to make it easier to understand. For example, the images are transformed into impact or change maps for rescue workers, flood alert maps for the public, and mapping of burnt or flooded areas with damage estimates for decision-makers.

Collaborative work between field users and satellite operators is essential. Progress has been made thanks to innovations in Earth observation technologies (notably the performance of optical resolutions – from 50 to 20 metres and now 30 centimetres) and 3D data processing software, but also thanks to the development of digital tools that can couple satellite and in situ data. The needs of the field have also contributed to the evolution of the charter’s intervention processes in terms of delivery time and quality of the products delivered.

Reconstruction after disasters

Emergency management is of course essential, but it is equally vital for all affected countries to consider reconstruction and the future. Indeed, the “risk cycle” posits that reconstruction, resilience and risk prevention all play an important role in the return to normality. While disasters cannot be predicted, they can be better prepared for, especially in countries where they are recurrent. For example, residents could benefit from earthquake-resistant construction, the creation of safe gathering places or relocating to living areas to safe locations. Learning survival skills is also crucial.

Several initiatives, called “reconstruction observatories”, have been carried out after major disasters – two examples are Haiti in 2021 and in Beirut after the 2019 port explosion. The aim is to coordinate satellite images to enable a detailed and dynamic assessment of damage to buildings, roads, farms, forests and more in the most affected areas, to monitor reconstruction planning, to reduce risks and to monitor changes over a three- to four-year time horizon.![]()

Emilie Bronner, Représentante CNES au Secrétariat Exécutif de la Charte Internationale Espace et Catastrophes Majeures, Centre national d’études spatiales (CNES)

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.