The first Earth Day was a shot heard around the world

iStock

Maria Ivanova, University of Massachusetts Boston

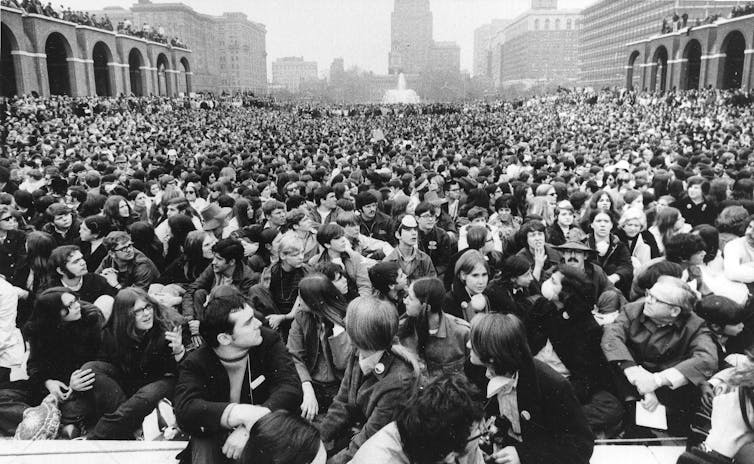

The first Earth Day protests, which took place on April 22, 1970 brought 20 million Americans – 10% of the U.S. population at the time – into the streets. Recognizing the power of this growing movement, President Richard Nixon and Congress responded by creating the Environmental Protection Agency and enacting a wave of laws, including the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act and the Endangered Species Act.

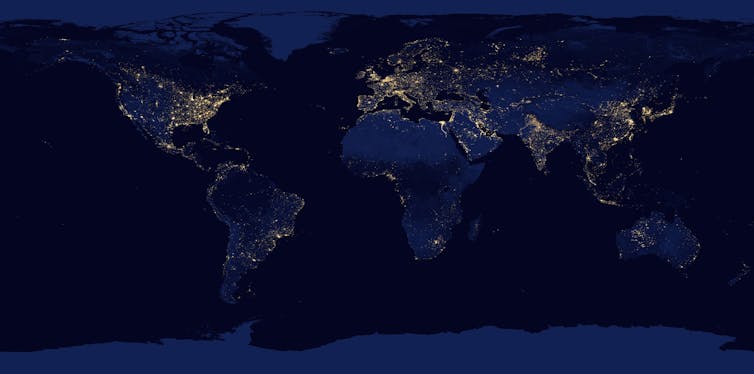

But Earth Day’s impact extended far beyond the United States. A cadre of professionals in the U.S. State Department understood that environmental problems didn’t stop at national borders, and set up mechanisms for addressing them jointly with other countries.

For scholars like me who study global governance, the challenge of getting nations to act together is a central issue. In my view, without the first Earth Day, global action against problems like trade in endangered species, stratospheric ozone depletion and climate change would have taken much longer – or might never have happened at all.

Alarms across the world

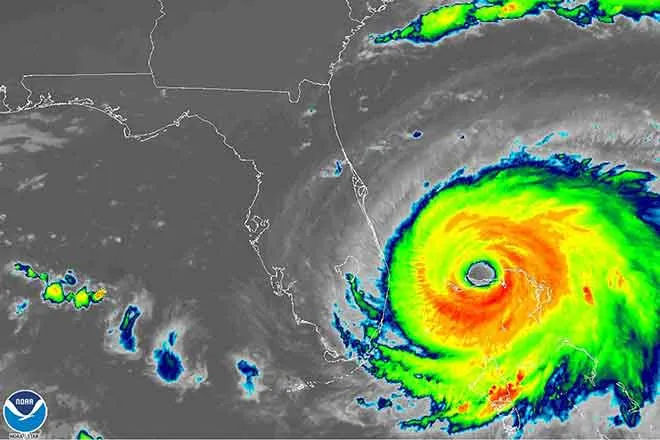

In 1970 governments around the world were contending with transborder pollution challenges. For example, sulfur and nitrogen oxides emitted from coal-fired power plants in the United Kingdom traveled hundreds of miles on northerly winds, then returned to earth in northern Europe as acid rain, fog and snow. This process was killing lakes and forests in Germany and Sweden.

Realizing that solutions would only be effective through common effort, countries convened the first global conference on the environment in Stockholm from June 5-16, 1972. Representatives of 113 governments attended and adopted the Stockholm Declaration on the Human Environment, which asserts that humans have a fundamental right to an environment that permits a life of dignity and well-being. They also passed a resolution to create a new international environmental institution.

Contrary to its posture today, the United States was an ardent proponent of the conference. The U.S. delegation advanced a series of actions, including a moratorium on commercial whaling, a convention to regulate ocean dumping and the creation of a World Heritage Trust to preserve wilderness areas and scenic natural landmarks.

President Nixon issued a statement when the conference concluded, observing that “for the first time in history, the nations of the world sat down together to seek better understanding of each other’s environmental problems and to explore opportunities for positive action, individually and collectively.”

Other nations were far more skeptical. France and the United Kingdom, for example, were wary of potential regulations that might hamper the British-French fleet of supersonic Concorde jet airliners, which had just entered operation in 1969.

Developing countries too were suspicious, viewing environmental initiatives as part of an agenda advanced by wealthy nations that would prevent them from industrializing. “I do not believe we are prepared to become new Robinson Crusoes,” Brazilian delegate Bernardo de Azevedo Brito stated in response to calls from industrialized countries to curb pollution.

A UN agency for the environment

Largely because of U.S. leadership, industrialized nations agreed to establish and provide initial funding for what is arguably the world’s premier global environmental institution: the United Nations Environment Programme. UNEP catalyzed negotiation of the 1985 Vienna Convention and its follow-on, the 1987 Montreal Protocol, a treaty to restrict production and use of substances that deplete Earth’s protective ozone layer. Today the agency continues to drive international efforts on issues including pollution control, biodiversity conservation and climate change.

John W. McDonald, who was director of economic and social affairs at the U.S. State Department’s Bureau of International Organization Affairs, had been circulating the idea of a new U.N. agency for the environment, and had garnered support from the Nixon administration. But creating a new international environmental institution could only happen with financial support from industrialized countries.

In an address to Congress on Feb. 8, 1972, Nixon proposed creating a US$100 million Environment Fund – close to $600 million in today’s dollars – to support effective international cooperation on environmental problems and create a central coordination point for U.N. activities. Recognizing that the United States was the world’s major polluter, the Nixon administration provided 30% of this sum over the first five years.

Over the next two decades the United States was the largest single contributor to the fund, which supports UNEP’s work worldwide. By the early 1990s, it was providing $21 million annually – equivalent to about $38 million in today’s dollars.

As I discuss in my forthcoming book on UNEP, however, after Republicans won control of both houses of Congress in 1994, the U.S. contribution dropped to $5.5 million in 1997. It has stayed at about $6 million per year since, a decrease of 84%. Today the U.S. contribution is 30% less than that of the Netherlands, whose economy is 20 times smaller.

Ceding leadership

Regrettably in my view, the United States has relinquished its longtime role as a leader on global environmental issues. President Trump has pursued what he calls an “America First” foreign policy that includes withdrawing from the Paris Climate Agreement and halting funding for the World Health Organization.

International problems demand global cooperation and leadership by example. Developing countries are more reticent to commit to multilateral agreements if the rich and powerful ones withdraw or defy the rules.

As political scientist and U.N. expert Edward Luck has written, the United States has swung for decades between embracing international organizations and rejecting them. When U.S. support ebbs, Luck observes, the U.N. is “in limbo, neither strengthened nor abandoned,” and the global community is less able to resolve fundamental problems.

The COVID-19 pandemic has laid bare nations’ inability to inspire, organize and finance a coordinated global response. No other government has yet been able to fill the void left by the United States.

I see the 50th anniversary of Earth Day as a fitting time to rethink American engagement in global governance. As President Nixon said in his speech outlining support for UNEP in 1972:

“What has dawned dramatically upon us in recent years … is a new recognition that to a significant extent man commands as well the very destiny of this planet where he lives, and the destiny of all life upon it. We have even begun to see that these destinies are not many and separate at all – that in fact they are indivisibly one.”

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]![]()

Maria Ivanova, Associate Professor of Global Governance and Director, Center for Governance and Sustainability, John W. McCormack Graduate School of Policy and Global Studies, University of Massachusetts Boston

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.