Historic power struggle between Trump and Congress to be reviewed by Supreme Court

Stanley M. Brand, Pennsylvania State University

On May 12, the Supreme Court will hear argument in two cases concerning congressional demands, known as subpoenas, for materials that President Donald Trump claims are intrusions into his private affairs and are not legitimate uses of congressional power.

One other case to be argued at the same time involves the Manhattan district attorney’s subpoena of records from Trump’s businesses as part of an investigation of state tax law violations. Trump is fighting that one, too.

Not since the “Red Scare” subpoena cases from the 1950s-1960s, where Congress conducted hearings that many called political witch hunts against alleged communists, and the Watergate era in the 1970s, when President Nixon claimed through his attorney that he was “as powerful a monarch as Louis XIV, only four years at a time, and is not subject to the processes of any court in the land except the court of impeachment,” has the Supreme Court taken up such far-reaching questions about the ability of Congress to oversee and check the president’s power.

Either Congress will be able to maintain its historic role of conducting oversight of the president and the executive branch, the president will be able to keep information secret no matter what – or the court will punt and the two branches of government will remain locked in the conflict.

From ethics to emoluments

Congress is investigating whether Trump used his power as president to profit his business, whether he accurately reported his finances as all government employees are required to do, and whether he accepted gifts from foreign governments without permission from Congress, which is banned by the Constitution. This ban reflected the Framers’ concern that no official be subject to foreign intrigue or influence of any kind — a common practice at the time among foreign sovereigns.

The first case, Trump v. Mazars, relates to those investigations. Trump is trying to stop his accountants and the bank he deals with from providing information subpoenaed by two House committees – oversight and intelligence.

Trump objected to these subpoenas on the grounds that they lack a legislative purpose and that their true aim is to obtain personal information for political advantage.

The Court of Appeals rejected this argument. It found that the records the congressional committees wanted were relevant to Congress’s legislative duties, and thus the subpoenas were legitimate.

All subpoenas from, and investigations by, Congress must have a legislative purpose. By law, Congress has the authority to pursue any “subject on which legislation can be had” as well as inquiries into fraud, waste and abuse in government programs. The broad standard for upholding that investigative power is affirmed in the Supreme Court’s ruling in McGrain v. Daugherty in 1927, which established that “the power of inquiry – with process to enforce it – is an essential and appropriate” aspect of how Congress carries out its legislative function.

Congress acted appropriately

The second case involves House committee subpoenas for Trump companies’ bank records from Deutsche Bank and Capital One. As with the Mazars case, Trump has tried to stop the banks from handing over the documents.

Those subpoenas are related to reviews by the House Financial Services Committee and the Intelligence Committee of the movement of illicit funds through the global financial system and money laundering. Deutsche Bank, which has loaned large amounts of money to Trump businesses, has already been fined $10 billion for a money laundering scheme unrelated to Trump.

The Court of Appeals rejected Trump’s argument and said Congress was legitimately entitled to pursue and get the records.

They wrote that the committees’ focus on illegal money laundering was not on any purported misconduct by Trump but instead on whether such activity occurred in the banking industry, the adequacy of banking regulation and the need for legislation to fix any problems — all legitimate oversight goals.

Nixon, Clinton precedents

Neither of these cases involves the president claiming executive privilege – the doctrine that keeps confidential many of the communications between the president and his closest advisers. Nor do the cases involve any challenge to the performance of his official duties.

Both concern only his private business activities before he assumed office. The records from before he was president are relevant because he refused to divest from his businesses, raising the concern whether his official actions once in office conflict with, or appear to conflict with, his existing business interests.

Two previous Supreme Court cases will in all likelihood weigh significantly in its decisions in these cases.

One is United States v. Nixon, which took place during the Watergate scandal, when Special Prosecutor Leon Jaworski subpoenaed the tape recordings of conversations between the president and four of his advisers who had been indicted. President Richard Nixon tried to claim executive privilege, saying the recordings of conversations between him and his advisers were confidential and should not be given to the special prosecutor.

The court ruled unanimously that the need for the tapes in the aides’ upcoming trial outweighed the president’s claim of confidentiality. And although no case applying the Nixon case precedent to a congressional subpoena has reached the Supreme Court, the implication drawn from the case is that if his privilege can be overcome by a subpoena for conversations with his closest aides, business records generated before a president came to office can legitimately be subpoenaed by Congress.

“The ruling rejected what it called the notion of ‘absolute, unqualified Presidential privilege of immunity from judicial process under all circumstances,’ which has an obvious impact on any president under serious suspicion, such as President Trump,” wrote presidential historian Michael Beschloss to a Washington Post reporter in 2018.

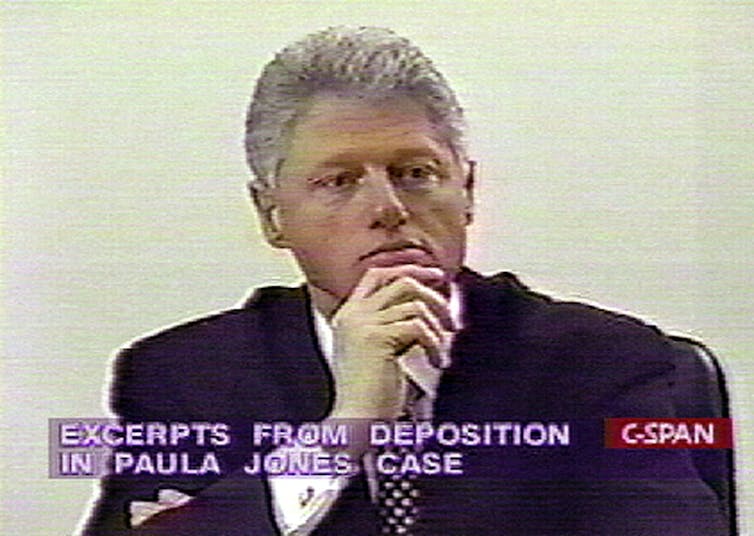

The other case relevant to these decisions is Clinton v. Jones. The case stemmed from a sexual harassment suit against Clinton concerning his conduct before his presidency. Clinton had refused to give a deposition in the case, insisting that it would be a distraction from his duties as president and an invitation to litigants to harass any president while in office with lawsuits.

The case description on the Supreme Court website asks, “Is a serving President … entitled to absolute immunity from civil litigation arising out of events which transpired prior to his taking office?”

The court’s answer: No.

Will the court rule?

These two decisions established precedents that seem to portend defeat for President Trump in the upcoming hearing.

Were the Supreme Court to validate Trump’s position in either case, or decline to decide the cases, it would stymie Congress and force it to seek enforcement by arresting those who refused to honor their subpoenas. That’s the way the Senate enforced its subpoena in the McGrain case and how Congress frequently operated in the 19th century.

The court has asked for additional briefing from the parties on whether the cases are not suitable for judicial decision as “political questions.” That legal doctrine says some cases are so politically freighted that the federal court system should not consider them – they should be resolved by the political players.

This has fueled speculation that the court may decide not to referee the dispute using the political doctrine as it has done in other cases involving disputes between Congress and the president over war powers or the disposition of the Panama Canal.

None of this indicates how the court will decide in the cases, only that whatever it decides will be momentous in the annals of congressional disputes with the president.

[You’re smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation’s authors and editors. You can read us daily by subscribing to our newsletter.]![]()

Stanley M. Brand, Distinguished Fellow in Law and Government, Pennsylvania State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.