How fierce fall and winter winds help fuel California fires

Faith Kearns, University of California, Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources and Max Moritz, University of California, Santa Barbara

It doesn’t take long in California to develop a feel for “fire weather.” When it’s hot and dry and the winds blow a certain way, there can be no doubt that, as in the past, landscapes will continue to be forged in fire.

And so, we residents of the state find ourselves again facing late fall wildfires that have scorched drought-parched vegetation while the rainy season evades its highly anticipated start. As the death toll and structure loss from fires burning in the northern and southern parts of the state continue to surpass records set not even a year ago, it is crucial to understand the role winds play in California fires.

Predictable but future unclear

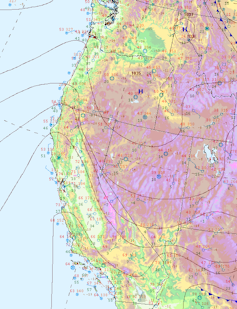

Across California, late fall winds – called by various names including Santa Anas, Diablos and sundowners – blow hot, dry air from the interior of the state out toward the coasts. The winds often intensify as they are channeled through mountain passes and then blasted across dry vegetation and steep surfaces to create the perfect conditions for fire. Given an ignition, those same winds then help to spread fire very quickly.

While these winds are in many ways predictable, they are also altering fire hazard in ways that researchers don’t fully understand. As the climate changes, bringing warmer temperatures and increasingly erratic precipitation patterns, more of these extreme wind events may occur during times that are highly conducive to fire.

It is also conceivable that climate change will cause shifts in the pressure patterns that spawn extreme wind events to begin with. Therefore, it is possible that in the future we may see extreme winds in new regions or during unexpected times of year. A deeper understanding of the controls on these events is emerging, but relatively little is known about what the future will hold.

Wind and fire risk

Fire hazard is determined by a variety of factors that include vegetation, topography and weather. Add people and homes, and you get fire risk. While wind is one of the biggest factors in fire spread, it also generates flying embers far ahead of the fire itself.

It is this storm of burning embers that often shower neighborhoods and ignite homes after finding vulnerable parts of landscaping and structures. Under the worst circumstances, wind driven home-to-home fire spread then occurs, causing risky, fast-moving “urban conflagrations” that can be almost impossible to stop and extremely dangerous to evacuate.

Managing the type and amount of vegetation, or “fuel,” in an area provides a set of tools for altering fire behavior in wildland fires. But during wind-driven urban conflagrations, homes are usually a major – if not the main – source of fuel.

Although defensible space immediately around homes is certainly important, vegetation management cannot be the sole solution. Fire-prone communities must also intensify urban and evacuation planning efforts that make the built environment and those living there less vulnerable to fires and the extreme winds that drive them.

Looking ahead

The most recent fires in California are sounding alarm bells that simply cannot be ignored, lest we fall into the trap of normalizing the incredible loss of lives and devastated communities year after year. Indeed, fire has become a critical public health and safety issue in this state.

As residents and researchers who have worked extensively on fire in California, we believe the state and its newly elected leadership face a formidable challenge and an opportunity to reinvest in a robust, interdisciplinary approach to wildfire risk reduction that combines the best of both research and practice. It must integrate both new (and potentially controversial) urban planning reforms as well as novel thinking about evacuation alternatives.

As it stands, California is failing to keep up with what we know about fire hazard and risk, and losing time as we struggle against rapidly changing climate conditions. Simply put: There is no time to waste.![]()

Faith Kearns, Academic Coordinator, California Institute for Water Resources, University of California, Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources and Max Moritz, Cooperative Extension Wildfire Specialist at the University of California Forest Research and Outreach; Adjunct Professor Bren School of Environmental Studies, University of California, Santa Barbara

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.