The National Hurricane Center’s forecasts in 2024 were its most accurate on record, from its one-day forecasts, as tropical cyclones neared the coast, to its forecasts five days into the future, when storms were only beginning to come together.

Thanks to federally funded research, forecasts of tropical cyclone tracks today are up to 75% more accurate than they were in 1990. A National Hurricane Center forecast three days out today is about as accurate as a one-day forecast in 2002, giving people in the storm’s path more time to prepare and reducing the size of evacuations.

Accuracy will be crucial again in 2025, as meteorologists predict another active Atlantic hurricane season, which runs from June 1 to Nov. 30.

Yet, cuts in staffing and threats to funding at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration – which includes the National Hurricane Center and National Weather Service – are diminishing operations that forecasters rely on.

I am a meteorologist who studies lightning in hurricanes and helps train other meteorologists to monitor and forecast tropical cyclones. Here are three of the essential components of weather forecasting that have been targeted for cuts to funding and staff at NOAA.

Tracking the wind

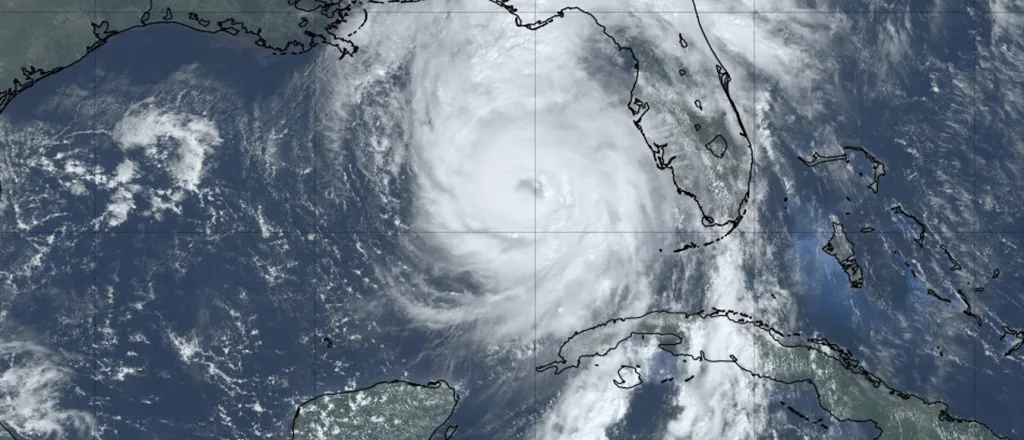

To understand how a hurricane is likely to behave, forecasters need to know what’s going on in the atmosphere far from the Atlantic and Gulf coasts.

Hurricanes are steered by the winds around them. Wind patterns detected today over the Rocky Mountains and Great Plains – places like Colorado, Wyoming, Nebraska and South Dakota – give forecasters clues to the winds that will be likely along the Gulf and Atlantic coasts in the days ahead.

Satellites can’t take direct measurements, so to measure these winds, scientists rely on weather balloons. That data is essential both for forecasts and to calibrate the complicated formulas forecasters use to make estimates from satellite data.

However, in early 2025, the Trump administration terminated or suspended weather balloon launches at more than a dozen locations.

That move and other cuts and threatened cuts at NOAA have raised red flags for forecasters across the country and around the world.

Forecasters everywhere, from TV to private companies, rely on NOAA’s data to do their jobs. Much of that data would be extremely expensive if not impossible to replicate.

Under normal circumstances, weather balloons are released from around 900 locations around the world at 8 a.m. and 8 p.m. Eastern time every day. While the loss of just 12 of these profiles may not seem significant, small amounts of missing data can lead to big forecast errors. This is an example of chaos theory, more popularly known as the butterfly effect.

The balloons carry a small instrument called a radiosonde, which records data as it rises from the surface of the Earth to around 120,000 feet above ground. The radiosonde acts like an all-in-one weather station, beaming back details of the temperature, relative humidity, wind speed and direction, and air pressure every 15 feet through its flight.

Together, all these measurements help meteorologists interpret the atmosphere overhead and feed into computer models used to help forecast weather around the country, including hurricanes.

Hurricane Hunters

For more than 80 years, scientists have been flying planes into hurricanes to measure each storm’s strength and help forecast its path and potential for damage.

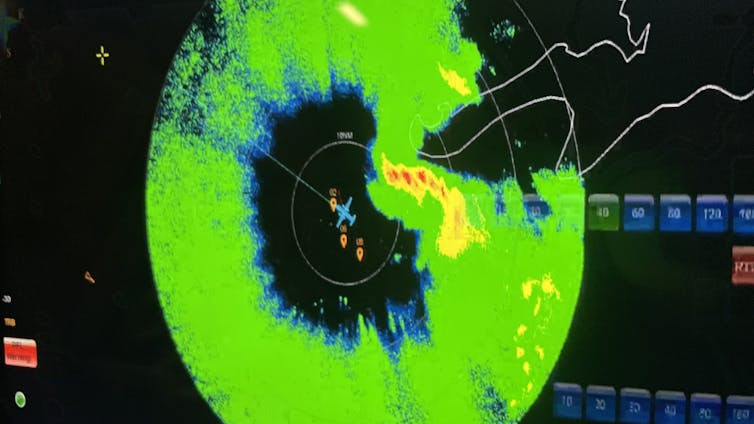

Known as “Hurricane Hunters,” these crews from the U.S. Air Force Reserve and NOAA routinely conduct reconnaissance missions throughout hurricane season using a variety of instruments. Similar to weather balloons, these flights are making measurements that satellites can’t.

Hurricane Hunters use Doppler radar to gauge how the wind is blowing and LiDAR to measure temperature and humidity changes. They drop probes to measure the ocean temperature down several hundred feet to tell how much warm water might be there to fuel the storm.

They also release 20 to 30 dropsondes, measuring devices with parachutes. As the dropsondes fall through the storm, they transmit data about the temperature, humidity, wind speed and direction and air pressure every 15 feet or so from the plane to the ocean.

Dropsondes from Hurricane Hunter flights are the only way to directly measure what is occurring inside the storm. Although satellites and radars can see inside hurricanes, these are indirect measurements that do not have the fine-scale resolution of dropsonde data.

That data tells National Hurricane Center forecasters how intense the storm is and whether the atmosphere around the storm is favorable for strengthening. Dropsonde data also helps computer models forecast the track and intensity of storms days into the future.

Two NOAA Hurricane Hunter flight directors were laid off in February 2025, leaving only six when 10 are preferred. Directors are the flight meteorologists aboard each flight who oversee operations and ensure the planes stay away from the most dangerous conditions.

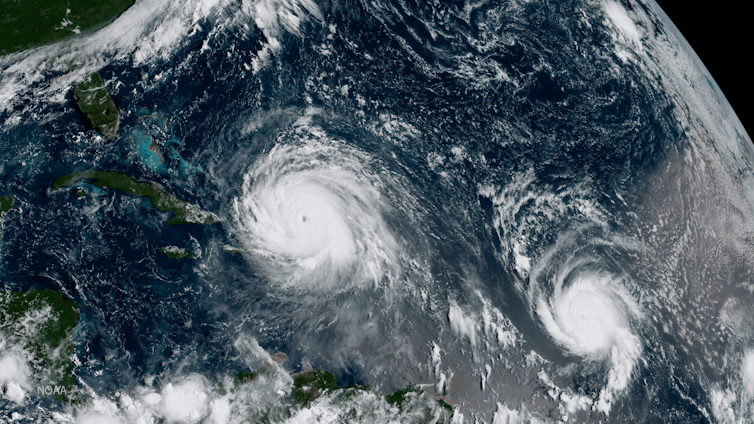

Having fewer directors limits the number of flights that can be sent out during busy times when Hurricane Hunters are monitoring multiple storms. And that would limit the accurate data the National Hurricane Center would have for forecasting storms.

Eyes in the sky

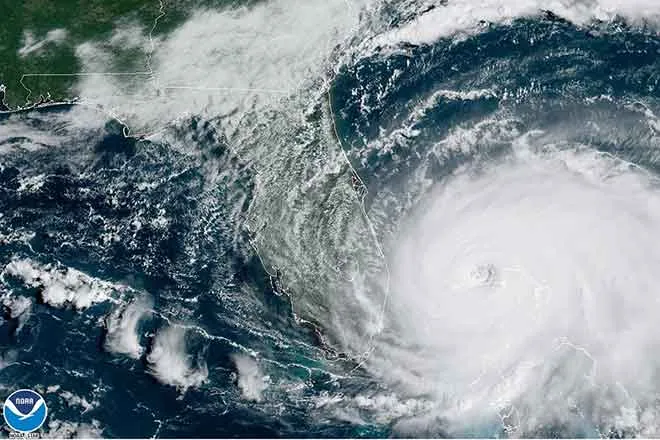

Weather satellites that monitor tropical storms from space provide continuous views of each storm’s track and intensity changes. The equipment on these satellites and software used to analyze it make increasingly accurate hurricane forecasts possible. Much of that equipment is developed by federally funded researchers.

For example, the Cooperative Institutes in Wisconsin and Colorado have developed software and methods that help meteorologists better understand the current state of tropical cyclones and forecast future intensity when aircraft reconnaissance isn’t immediately available.

Forecasting rapid intensification is one of the great challenges for hurricane scientists. It’s the dangerous shift when a tropical cyclone’s wind speeds jump by at least 35 mph (56 kilometers per hour) in 24 hours.

For example, in 2018, Hurricane Michael’s rapid intensification caught the Florida Panhandle by surprise. The Category 5 storm caused billions of dollars in damage across the region, including at Tyndall Air Force Base, where several F-22 Stealth Fighters were still in hangars.

Under the federal budget proposal details released so far, including a draft of agencies’ budget plans marked up by Trump’s Office of Management and Budget, known as the passback, there is no funding for Cooperative Institutes. There is also no funding for aircraft recapitalization. A 2022 NOAA plan sought to purchase up to six new aircraft that would be used by Hurricane Hunters.

The passback budget also cut funding for some technology from future satellites, including lightning mappers that are used in hurricane intensity forecasting and to warn airplanes of risks.

It only takes one

Tropical storms and hurricanes can have devastating effects, as Hurricanes Helene and Milton reminded the country in 2024. These storms, while well forecast, resulted in billions of dollars of damage and hundreds of fatalities.

The U.S. has been facing more intense storms, and the coastal population and value of property in harm’s way are growing. As five former directors of the National Weather Service wrote in an open letter, cutting funding and staff from NOAA’s work that is improving forecasting and warnings ultimately threatens to leave more lives at risk.![]()

Chris Vagasky, Meteorologist and Research Program Manager, University of Wisconsin-Madison

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.