Liz Truss: the financial whirlwind facing the new prime minister

Steve Schifferes, City, University of London

Liz Truss may have won the battle to become Britain’s next prime minister, but don’t expect much time for her to settle into office. People’s living standards are predicted to fall by an unprecedented 10% over the next two years, driven by rising prices of energy and other goods.

The UK economy is facing a recession by the end of this year, with virtually no economic growth predicted until 2024. Inflation, already at 10%, could rise, according to some forecasters, to over 20%. This will hit public services like health, education and policing which are already being strained by tight government finances.

Meanwhile, the crisis is highlighting the UK’s long-term structural problems: it lags behind rivals in terms of economic growth, inequality and productivity. Real incomes for most households have not grown for the last decade, while there has not been enough investment to raise productivity.

Big differences in productivity also underly the gap between London and the south-east compared to the rest of the country, which “levelling up” was aimed at tackling.

Who to help?

With the average annual household power bill set to nearly double to over £3,500 in October thanks to a steep rise in the energy price cap – and potentially over £6,000 by April – millions more families will be pushed into poverty. While Truss may have won the Tory leadership election by extolling tax cuts and free markets, she says she will introduce emergency measures in her first week in office to tackle the energy crisis which will provide new government support for households and businesses.

This will come at a hefty price. Following the latest increase in the energy price cap, merely boosting the existing subsidy package so that it still absorbs three-quarters of the rise in bills will raise the cost to the government from £24 billion to £42 billion. In her campaign, Truss additionally talked about cutting VAT on fuel bills and suspending the “green levy” that everyone pays towards the cost of renewable energy, but these will only be of limited help.

She may favour a targeted and temporary approach to giving further assistance, increasing existing grants for pensioners and those on benefits as the cap rises further. But the politics are such that directly tackling the price of energy may also be necessary, perhaps via the Labour party’s proposal to freeze the price cap for six months. That would cost £38 billion, and even more if energy prices keep rising in the meantime.

Trussonomics

The new government has also pledged to introduce an emergency budget within a month to to reverse the recent increase in national insurance contributions and stop the corporation tax increase scheduled for April 2023, which will cost £13 billion and £17 billion respectively. This immediately wipes out the projected “fiscal headroom” of £30 billion projected in March by the government’s Office of Budget Responsibility (OBR), even before taking into account a coming recession reducing tax revenues and requiring increased spending on benefits.

Yet these moves will have a limited effect on the cost of living. More radical tax cuts such as an overall cut in VAT or income tax would cost much more. For example, Truss’s suggestion of a 5% cut in VAT duty would cost £38 billion. At the same time, her government seems intent on weakening the fiscal rules that have previously guided spending decisions.

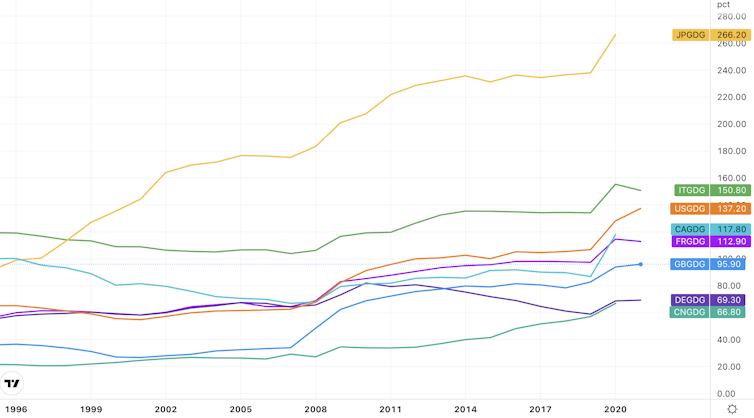

Many economists believe that stimulating the economy with big tax cuts and extra spending would further increase inflation, forcing the Bank of England to raise interest rates higher and do more damage to growth. Then there is government debt, which already stands at 100% of GDP. Truss has argued that since rivals like the US and Canada are even more indebted, the UK can raise debt higher.

Major economies’ public debt to GDP

But this will further limit its spending capacity. Government annual debt interest payments are already forecast by the OBR to hit £83 billion in 2022. That’s more than 3% of GDP and almost as much as the entire education budget, and the debt payments may come in even higher – especially if international investors become reluctant to finance UK borrowing. With the pound already hitting lows not seen since the 1980s, confidence is not high in the UK economy.

The new government argues that the pay-off from big tax cuts will be more economic growth, which would boost tax revenues and cut the deficit in years to come. In my view, Truss is certainly correct to identify the biggest long-term problems facing the economy as low growth and low productivity. But every post-war government has tried to boost productivity, with limited success.

The evidence is not convincing that cutting taxes alone is the answer, however. The US attempt to do something similar under Ronald Reagan is not an encouraging precedent. US tax cuts in the early 1980s did not pay for themselves, but did stoke inflation as government spending was not cut and the public deficit ballooned. The Federal Reserve under Paul Volcker was forced to raise interest rates sharply, curbing inflation but causing the “Volcker recession”.

The Thatcher government took a different approach, raising taxes in her first term to bring the budget into balance before cutting income tax rates. There was a boost in productivity, but the key factors were the privatisation of inefficient state industries and the weakening of union bargaining power.

State-shrinking

Truss has been reluctant to discuss the corollary of big tax cuts – the need to shrink the state. Already, the government plans to sharply constrain rises in public sector workers’ pay – the biggest part of government spending – to well below inflation. This may spark strikes and a recruitment crisis for the understaffed NHS.

It is also planning major cuts in the number of civil servants and other parts of the public sector workforce. This will exacerbate existing problems in delivering many key services. Truss’s plan to cut bureaucracy and waste while “giving more money to front-line services” will not be enough to avoid this. Note that some key Truss allies, including Brexit minister Jacob Rees-Mogg, believe that “rather than looking for fiscal trims and haircuts, [we should] consider whether the state should deliver certain functions at all”.

There has also been little mention of levelling up. As the government’s own white paper made clear earlier this year, it requires substantial long-term government investment in infrastructure and training in the so-called “red wall” areas in northern England that traditionally vote Labour but switched to Tory to give Boris Johnson his sizeable majority in 2019.

Squaring the circle of the public’s demands for better services and cost-of-living support with the government’s desire for lower taxes is the central dilemma that will face Truss. The decisions made in the next few months will affect not only the economic situation of every household in the country, but the fate of the new government as it faces a general election within the next two years.![]()

Steve Schifferes, Honorary Research Fellow, City Political Economy Research Centre, City, University of London

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.