New Federal Rules Aim to Speed Repatriations of Native Remains and Burial Items

ProPublica is a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom. Sign up for The Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox.

Series: The Repatriation Project:The Delayed Return of Native Remains

America’s institutions maintain control of more than a hundred thousand remains of Native Americans as well as sacred items. A federal law, the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, was meant to help return them, but decades after its 1990 passage, many tribes are still waiting.

The Biden administration has revised the rules that institutions and government agencies must follow to comply with the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act — a law long hampered by limited funding and the unwillingness of many museums to relinquish Indigenous remains and burial items.

Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, the first Native American to hold a U.S. cabinet position, said Wednesday that the regulations will “strengthen the authority and role of Indigenous communities in the repatriation process” by requiring institutions to defer more to tribes’ knowledge of their regions and histories in their decision-making about repatriations.

Thirty-three years ago, Congress passed NAGPRA to prevent grave looting and push museums to return human remains and items excavated from Native American gravesites to tribes. But the promise of repatriation that many tribal nations once saw in the law has not been fully realized, with federal data showing institutions continue to store about half of the 200,000 ancestral remains they reported holding following passage of the 1990 law.

This year, ProPublica’s Repatriation Project investigative series revealed that archaeologists and scientists at some of the nation’s top universities and museums have exploited loopholes in NAGPRA to delay or resist turning over holdings reported under the law.

“Finalizing these changes is an important part of laying the groundwork for the healing of our people,” Haaland said in a written statement.

Haaland described NAGPRA as an essential tool for the “return of sacred objects and ancestral remains to the communities from which they were stolen,” though senior administration officials also acknowledged that getting institutions to comply with the law has long been a challenge.

As we reported this year, institutions have dismissed tribes’ oral histories and other evidenceof a connection to the ancestors they sought to claim, saying that not enough information was available to conduct repatriation. In these cases, museums have declared the human remains and items “culturally unidentifiable,” which allowed them to be used for scientific research over tribes’ objections.

ProPublica also found that since the 1990s researchers have routinely obtained federal research grantsto conduct radiocarbon dating, DNA extractions and bone chemistry analyses on Native American remains that Congress expected would have been repatriated within a decade of the law’s passage. This research gives scientists insight into the diets, ages and genetics of ancient populations but requires destroying small portions of bone. Tribes have long asked to be consulted on such research or opposed it altogether because the destruction of ancestral remains, like grave looting, violates deeply held religious beliefs.

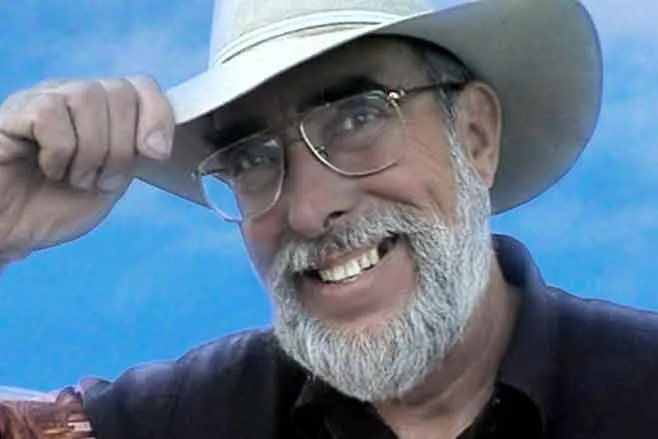

“We know that research and scientific studies have been conducted on most, if not all, of our stolen ancestors and their burial property,” Mark Fox, chairman of the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation in North Dakota, wrote in a letter to Haaland earlier this year. “We also know that is why NAGPRA is almost 33 years old, and many museums and all of the federal agencies are still not in full compliance with the Act.”

The new regulations will direct institutions to defer to tribal nations’ knowledge of their customs, traditions and histories when making repatriation decisions. The rules will also eliminate the “culturally unidentifiable” designation. Museums will be required to determine, in consultation with tribes, which community can rightfully claim human remains or items in their collections. If a museum finds that it still cannot make a determination, it would have to say why in a notice filed in the Federal Register, said Melanie O’Brien, program manager of the National NAGPRA Program, an office within the Interior Department’s National Park Service.

The regulations are largely consistent with draft rules the department proposed late last year. However, some changes have been made following a monthslong public comment period and a year of heightened media attention on repatriation in response to ProPublica’s reporting.

The law initially required institutions to inventory the human remains and belongings of Native American ancestors and burial items and identify those that might be repatriated. The new regulations will give institutions five years to update those inventories and publish them in the Federal Register. Initially, the Interior Department proposed a two-year deadline, but it extended it after tribes and museums said this would not allow enough time for the consultations between museums and tribes that the law requires before repatriation.

The final regulations also include firmer mandates for institutions to obtain tribal consent before allowing Native American remains and items held in museum collections to be used for research.

Last year, the Interior’s proposed regulations said institutions should limit scientific research “to the maximum extent” feasible at the request of a tribe. The regulations will now require institutions to seek or obtain “free, prior and informed consent” from tribes before allowing any research to happen.

The finalization of the new federal regulations was publicly announced Wednesday during the White House Tribal Nations Summit, an annual meeting in Washington of tribal leaders and federal officials. The regulations are set to go into effect next month.