Pessimists have been saying America is going to hell for more than 200 years

Maurizio Valsania, Università di Torino

Pessimism looms large in America today. It’s not just because of Donald Trump, the vicar of fear and violence. It’s COVID-19, a faltering economy, the growing power of Russia and China, fires and climate change – you name it.

Journalists and analysts have launched warnings: American democracy is about to end; the American century is about to end; the American era is about to end. If Trump loses, there’s no certainty that the U.S. will make it to the other side of potential political chaos.

That’s no delusion. The bleak scenarios are a possibility, although the probability is that the United States will not descend, any time soon, into a second Civil War. The presidential election could well be contested – although the nation will probably survive intact.

This is not the first time in American history that journalists, writers and intellectuals in general have cast a gloomy light about the future. American leaders as well have often yielded to despair – which is especially notable given that political leaders are expected to be the most optimistic of the herd.

‘We are not a chosen people’

During the early stages of national life, the mood was no different. Actually, it was even worse.

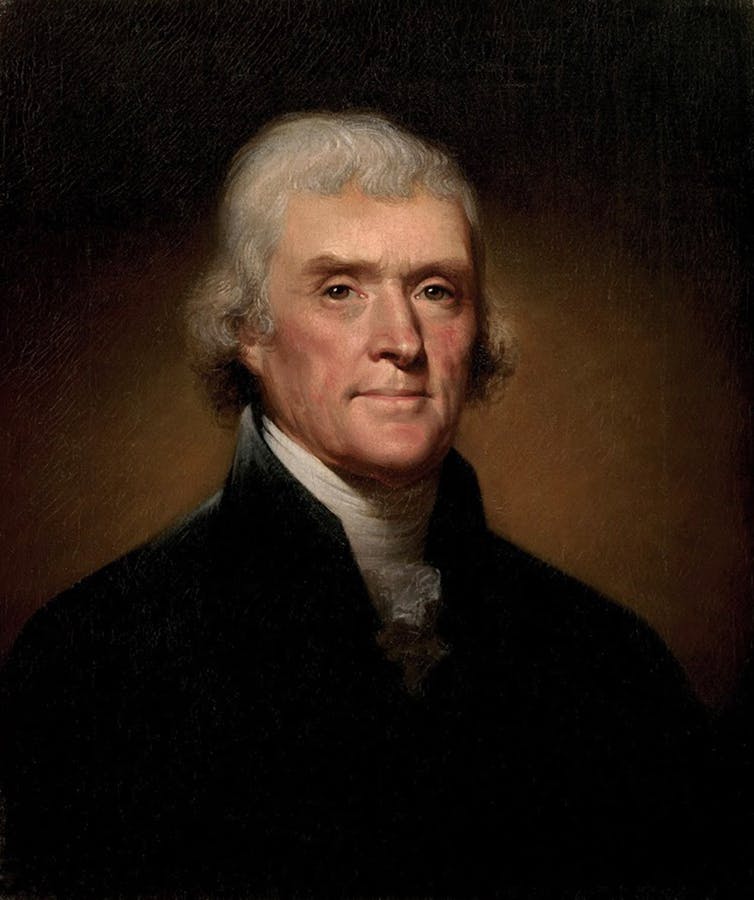

When Thomas Jefferson realized the implications of grounding a nation upon slavery, his pessimism reached metaphysical, theological heights:

“I tremble for my country when reflect that God is just: that his justice cannot sleep for ever.”

John Adams, the second president, was similarly prone to frequent bouts of pessimism.

“Our country will do like all others,” he wrote a few years before entering office, “play their affairs into the hands of a few cunning fellows.”

Then he went through his painful presidency, a single term only, which made him even more bitter: “There is no special Providence for us. We are not a chosen people that I know of.”

Fending off ruin

Back then, France and Great Britain acted like the global superpowers. The “American experiment,” on the other hand, was puny, defenseless, hazardous. Consequently, many leaders believed that only a constitution, plus a stronger central government, could forestall ruin.

When Alexander Hamilton, James Madison and John Jay set off to write the famous 85 papers to persuade Americans to adopt the new national charter, pessimism was one of their favorite vocabularies. It was more than just a rhetorical expedient. These men were convinced that society was actually teetering on the edge of the abyss.

Americans would soon behold “plunder and devastation,” Hamilton wrote. Madison echoed his colleague and conjured a “gloomy and perilous scene into which the advocates for disunion would conduct us.”

The “advocates for disunion” – the antagonist political party led by James Winthrop from Massachusetts, Melancton Smith from New York and Patrick Henry and George Mason from Virginia – would sap America of all its good energy. “Poverty and disgrace,” Hamilton wrote again, “would overspread a country which with wisdom might make herself the admiration and envy of the world.”

At the end of the 18th century, negative campaigning was already widespread. Political candidates and their acolytes criticized their competitors and conjured images of destruction if their rivals prevailed.

If Jefferson were to be elected, one Connecticut newspaper announced, “murder, robbery, rape, adultery and incest, will openly be taught and practiced, the air will be rent with the cries and distress, the soil soaked with blood, and the nation black with crimes.”

Political campaigning and statements bordering on exaggeration should not be taken at face value. But it’s also true that today, like yesterday, a genuine pessimism about America’s future exists.

A patriotic feat

As a historian of the early republic, I dare say that pessimism is to America what salt is to french fries: without, it wouldn’t be the same.

However, there are two types of pessimism in America, absolute and conditional – a distinction that political scientist Francis G. Wilson laid out long ago.

Absolute pessimism is the belief that the nation is a big lie, a fraud, a trick that cunning white males have been playing on women, native populations, African Americans, working classes, immigrants. As such, this nation deserves to be cursed, canceled, sunk, forgotten.

Most leaders, journalists, analysts and historians do not endorse this kind of pessimism. They are conditional pessimists, as Wilson would label them.

They are like Jeremiah, the weeping prophet of the Bible. They deliver a prophecy of disaster because they want to provide a new hopeful solution. They speak to Americans’ sense of pride, exhort them, incite them, mobilize them, increase the level of commitment to a common cause and enact a ritual whose upshot should be a deeper awareness.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

To repeat: The worst can happen – is happening – today, just as it did 200-something years ago. That’s why these contemporary prophets are not delusional conspiracy theorists, or simply paranoids.

Their pessimism is fact based. At the same time, it’s a patriotic feat. Conditional pessimists evoke images of turbulence and peril. But they call on America to be its best self.

Pessimism, in this case, is optimism by another name.![]()

Maurizio Valsania, Professor of American History, Università di Torino

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.