Study: Wildfire burn areas see faster snowpack melts, disrupt water resources

Click play to listen to this article.

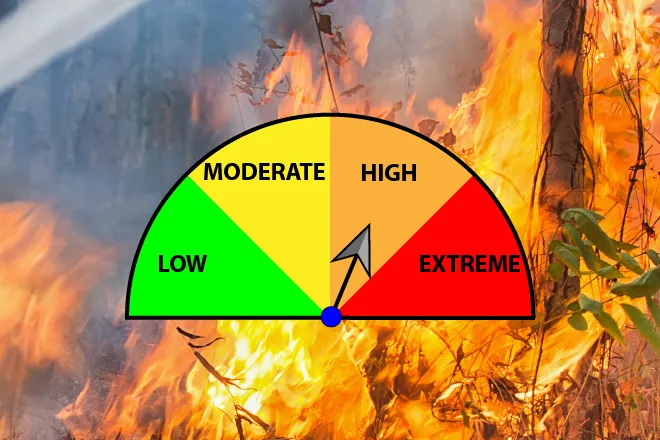

(Colorado News Connection) As a warming climate brings bigger and more frequent wildfires, burn scars left behind at high mountain altitudes are seeing snowpack melt much faster than non-burned areas, according to new research by Colorado State University.

Wyatt Reis, lead author of the study while a graduate student, said snowpacks act as massive water reservoirs during winter months. Until now, they have melted slowly in the spring sending water used for drinking, agriculture and other uses to millions in Colorado and across the West.

Mountains in Colorado. © Chris Sorensen / KiowaCountyPress.net

"Those snowpacks melting at a quicker rate puts more stress on the infrastructure that we have in place, that will need to be managed differently so that there is enough water for those downstream uses," Reis explained.

Rising temperatures have already changed the timing of when snow melts and the state's water managers are working to capture earlier flows. Reis pointed out the trend is likely to accelerate as more fires create conditions for even faster melts. Researchers found snowpacks on south-facing slopes scorched by the Cameron Peak Fire reached their maximum level 22 days earlier than north facing slopes and the snow melted completely a full 11 days earlier.

Snowpacks in burned areas stay colder in winter, due to a lack of thermal energy normally produced by trees, but the energy balance flips during warmer months when there is no shade from the sun. Reis added earlier snow melts in burn areas are also making it more challenging for forests and other vegetation to recover.

"Currently there is nearly no canopy in these burned areas," Reis observed. "That canopy is going to take decades, if it ever regrows, just due to climate change and changing environments."

Wildfires are increasingly burning at high elevations where deep snowpacks accumulate and Reis expects it will present persistent challenges for water managers in Colorado and across the Mountain West.

"That's just going to continue to have major impacts on our water resources for decades to come," Reis projected. "The impact of that, as more fires are continuing, is going to be cumulative."