These CRISPR-modified crops don't count as GMOs

iStock - IMNATURE

Yi Li, University of Connecticut

To feed the burgeoning human population, it is vital that the world figures out ways to boost food production.

Increasing crop yields through conventional plant breeding is inefficient – the outcomes are unpredictable and it can take years to decades to create a new strain. On the other hand, powerful genetically modified plant technologies can quickly yield new plant varieties, but their adoption has been controversial. Many consumers and countries have rejected GMO foods even though extensive studies have proved they are safe to consume.

But now a new genome editing technology known as CRISPR may offer a good alternative.

I’m a plant geneticist and one of my top priorities is developing tools to engineer woody plants such as citrus trees that can resist the greening disease, Huanglongbing (HLB), which has devastated these trees around the world. First detected in Florida in 2005, the disease has decimated the state’s US$9 billion citrus crop, leading to a 75 percent decline in its orange production in 2017. Because citrus trees take five to 10 years before they produce fruits, our new technique – which has been nominated by many editors-in-chief as one of the groundbreaking approaches of 2017 that has the potential to change the world – may accelerate the development of non-GMO citrus trees that are HLB-resistant.

Genetically modified vs. gene edited

You may wonder why the plants we create with our new DNA editing technique are not considered GMO? It’s a good question.

Genetically modified refers to plants and animals that have been altered in a way that wouldn’t have arisen naturally through evolution. A very obvious example of this involves transferring a gene from one species to another to endow the organism with a new trait – like pest resistance or drought tolerance.

But in our work, we are not cutting and pasting genes from animals or bacteria into plants. We are using genome editing technologies to introduce new plant traits by directly rewriting the plants’ genetic code.

This is faster and more precise than conventional breeding, is less controversial than GMO techniques, and can shave years or even decades off the time it takes to develop new crop varieties for farmers.

There is also another incentive to opt for using gene editing to create designer crops. On March 28, 2018, U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue announced that the USDA wouldn’t regulate new plant varieties developed with new technologies like genome editing that would yield plants indistinguishable from those developed through traditional breeding methods. By contrast, a plant that includes a gene or genes from another organism, such as bacteria, is considered a GMO. This is another reason why many researchers and companies prefer using CRISPR in agriculture whenever it is possible.

Changing the plant blueprint

The gene editing tool we use is called CRISPR – which stands for “Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats” – and was adapted from the defense systems of bacteria. These bacterial CRISPR systems have been modified so that scientists like myself can edit the DNA of plants, animals, human cells and microorganisms. This technology can be used in many ways, including to correct genetic errors in humans that cause diseases, to engineer animals bred for disease research, and to create novel genetic variations that can accelerate crop improvement.

To use CRISPR to introduce a useful trait into a crop plant, we need to know the genes that control a particular trait. For instance, previous studies have revealed that a natural plant hormone called gibberellin is essential for plant height. The GA20-ox gene controls the quantity of gibberellin produced in plants. To create a breed of “low mowing frequency” lawn grass, for example, we are editing the DNA – changing the sequence of the DNA that makes up gene – of this plant to reduce the output of the GA20-ox gene in the selected turf grass. With lower gibberellin, the grass won’t grow as high and won’t need to be mowed as often.

The CRISPR system was derived from bacteria. It is made up of two parts: Cas9, a little protein that snips DNA, and an RNA molecule that serves as the template for encoding the new trait in the plant’s DNA.

To use CRISPR in plants, the standard approach is to insert the CRISPR genes that encode the CRISPR-Cas9 “editing machines” into the plant cell’s DNA. When the CRISPR-Cas9 gene is active, it will locate and rewrite the relevant section of the plant genome, creating the new trait.

But this is a catch-22. Because to perform DNA editing with CRISPR/Cas9 you first have to genetically alter the plant with foreign CRISPR genes – this would make it a GMO.

A new strategy for non-GMO crops

For annual crop plants like corn, rice and tomato that complete their life cycles from germination to the production of seeds within one year, the CRISPR genes can be easily eliminated from the edited plants. That’s because some seeds these plants produce do not carry CRISPR genes, just the new traits.

But this problem is much trickier for perennial crop plants that require up to 10 years to reach the stage of flower and seed production. It would take too long to wait for seeds that were free of CRISPR genes.

My team at the University of Connecticut and my collaborators at Nanjing Agricultural University, Jiangsu Academy of Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida, Hunan Agricultural University and University of California-San Diego have recently developed a convenient, new technique to use CRISPR to reliably create desirable traits in crop plants without introducing any foreign bacterial genes.

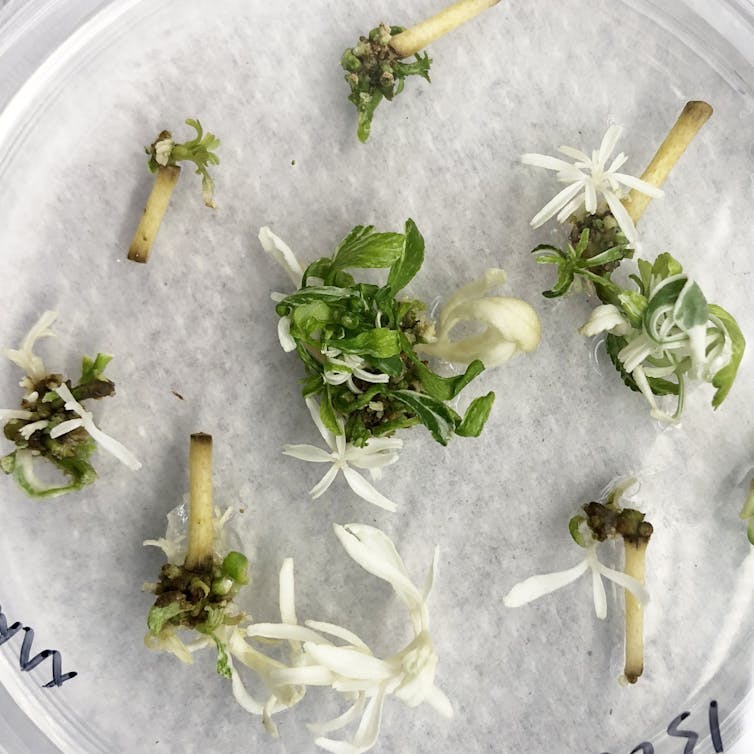

We first engineered a naturally occurring soil microbe, Agrobacterium, with the CRIPSR genes. Then we take young leaf or shoot material from plants and mix them in petri dishes with the bacteria and allow them to incubate together for a couple of days. This gives the bacteria time to infect the cells and deliver the gene editing machinery, which then alters the plant’s genetic code.

In some Agrobacterium infected cells, the Agrobacterium basically serves as a Trojan horse, bringing all the editing tools into the cell, rather than engineering plants to have their own editing machinery. Because the bacterial genes or CRISPR genes do not become part of the plant’s genome in these cells – and just do the work of gene editing – any plants derived from these cells are not considered a GMO.

After a couple of days, we can cultivate plants from the edited plant cells. Then it take several weeks or months to grow an edited plant that could be planted on a farm. The hard part is figuring out which plants are successfully modified. But we have a solution to this problem too and have developed a method that takes only two weeks to identify the edited plants.

Genetically designed lawns

One significant difference between editing plants versus human cells is that we are not as concerned about editing typos. In humans, such errors could cause disease, but off-target mutations in plants are not a serious concern. A number of published studies reported low to negligible off-target activity observed in plants when compared to animal systems.

Also, before distributing any plants to farmers for planting in their field, the edited plants will be carefully evaluated for obvious defects in growth and development or their responses to drought, extreme temperatures, disease and insect attacks. Further, DNA sequencing of edited plants once they have been developed can easily identify any significant undesirable off-target mutations.

In addition to citrus, our technology should be applicable in most perennial crop plants such as apple, sugarcane, grape, pear, banana, poplar, pine, eucalyptus and some annual crop plants such as strawberry, potato and sweet potato that are propagated without using seeds.

![]() We also see a role for genome editing technologies in many other plants used in the agricultural, horticultural and forestry industries. For example, we are creating lawn grass varieties that require less fertilizer and water. I bet you would like that too.

We also see a role for genome editing technologies in many other plants used in the agricultural, horticultural and forestry industries. For example, we are creating lawn grass varieties that require less fertilizer and water. I bet you would like that too.

Yi Li, Professor of Plant Science, University of Connecticut

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.