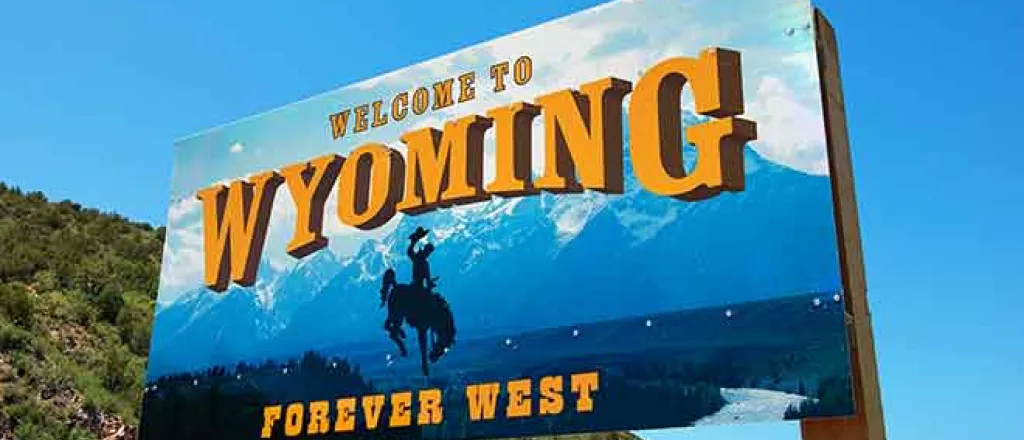

Uncovering Wyoming's Hispanic heritage along Manito Trail

(Wyoming News Service) While many Wyomingites of Hispanic descent came from Mexico, there is a lesser-known population from the old Spanish settlements of northern New Mexico who made significant contributions to the state's cultural heritage and economic growth.

Trisha Martinez, assistant professor of Latino studies at the University of Wyoming, has been documenting oral histories of families who came to the Cowboy State along the Manito Trail, a corridor now occupied by Interstate 25. She said most came to work and support their families.

"In Northern New Mexico, the reality was really hard in terms of socio-economic conditions," Martinez explained. "And so, migrating outside of the state was a necessity for survival."

Workers from New Mexico and southern Colorado were recruited to work on the railroad, in the sugar beet industry, and as sheepherders in the early twentieth century, and now have permanent communities in the state going back several generations.

Most sheepherders in the Sierra Madres of southern Wyoming traveled along the Manito Trail, and many made long-lasting impressions on Aspen trees.

Amanda Castaneda, state coordinator for the Wyoming State Historic Preservation Office, said arborglyphs were created with sharp tools carving thin lines, which would expand as the trees grew. Many were straightforward, featuring family names or dates.

"You're also seeing some really beautiful drawings," Castaneda observed. "A lot of religious imagery, glamorous women with 40s and 50s style haircuts. So, you can come across some pretty striking artistic accomplishments in the forest."

Workers and their families settled in segregated Laramie's west side, the south side of Cheyenne, the south park barrio of Riverton, and the south side of Rawlins, where residents still maintain traditions from their home region.

Martinez added many of her students are surprised to learn their direct ancestors traveled the Manito Trail.

"They go home and they ask questions, they call their grandparents to learn more," Martinez noted. "When students explore their communities and histories, they affirm their connection to ancestral knowledge and life-producing energies."