What House Republicans got in return for pushing the US to the brink of default

Raymond Scheppach, University of Virginia

House Republicans pushed the U.S. to the edge of a fiscal crisis because they wanted deep cuts in government spending.

So, based on the tentative deal announced on May 27, 2023, how did they do?

In broad strokes, the deal would suspend the debt limit until January 2025, freeze nondefense discretionary funding at current levels and make a few additional cuts and policy changes designed to appeal to enough Republicans and Democrats to get it through Congress. The deal also included incentives to motivate lawmakers to pass a budget on time in four months.

That provision and the 2025 expiration date should mean the U.S. should avoid a self-inflicted fiscal crisis – including an unprecedented default – until at least after the next presidential election.

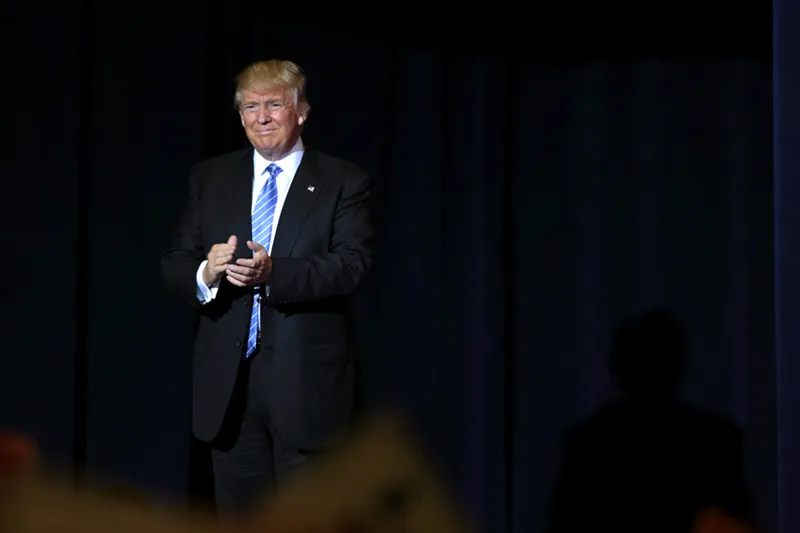

No one got everything they wanted. President Joe Biden didn’t get the clean debt ceiling increase he had insisted on for months. Republicans didn’t get most of what they sought in a bill they passed in April – though they did get some of it.

As a professor of public policy and former deputy director at the Congressional Budget Office, I believe the deal, which still needs to pass both houses of Congress by June 5 to avoid a default, does hardly anything to address America’s long-term debt problem, which to me shows why a debt ceiling standoff is not the right way to solve it.

Let’s take a closer look at what I would consider the five main components of the deal to see what they’ll accomplish.

1. Expanded work requirements for SNAP

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program has been a Republican target for a while.

Under current law, an individual must work or be in training for 80 hours per month if they receive SNAP food benefits in three or more out of 36 months, is able-bodied, does not live with dependent children and is under 50 years old. This entitlement program is 100% funded by the federal government but is administered by states, which have the ability to waive the requirements in some low unemployment areas.

The new deal would expand the definition to people up to age 54 and limit some of the state waiver authority. It would exclude veterans and homeless people from the tougher work requirements and expire in 2030.

The Congressional Budget Office had estimated that a similar provision in the House bill – based on extending the age requirement to 55 – would kick 275,000 people off the SNAP roles and save US$11 billion over a decade.

Since states would have to expand their work reporting systems, their increased costs would offset some of the federal savings.

The bill also contains some additional work requirements for welfare recipients for the temporary assistance for needy families program, but the changes are relatively minor.

2. Cap on nondefense discretionary spending

The main way the agreement would restrict federal spending is through the temporary cap on nondefense discretionary spending.

Spending on everything other than defense, entitlements like Social Security and veterans benefits, would stay flat in next year’s budget relative to the 2023 amount and increase 1% the following year, with no limits after that.

But, ultimately, the caps apply to just a small share of total government spending – less than 13%. So not only is it a very minor reduction in spending, it involves a small fraction of the federal budget.

In their House bill, Republicans had sought a larger cut in discretionary spending.

Entitlement programs would be unaffected by the deal, while defense spending would grow by 3.3% next year, as Biden requested in his budget.

One item that would see actual cuts would be the $80 billion that had previously been allocated to beef up IRS enforcement of tax cheats. The deal would trim that by about $20 billion, and the savings would be used to offset cuts to other areas of discretionary spending.

Republicans had wanted to slash this by $71 billion – which, ironically, would have actually resulted in a larger budget deficit because much of that money was going to be used to beef up enforcement to collect more revenue from people who didn’t pay all the taxes they owed.

3. Streamlining energy leasing and permitting

Both Republicans and Democrats have interest in expediting the environmental review process for new energy leases, but they have very different priorities.

Republicans are more interested in gas pipelines and fossil fuel projects, while Democrats are more interested in wind, solar and other alternative energy installations. The problem for both is that the approval of environmental and technical plans is very slow and often involves all three levels of government. Also, at the federal level decisions often involve federal agencies with overlapping jurisdictions.

The new deal would make some minor changes to the environmental review process to make it go faster – though it’s less than what Republicans initially wanted.

4. COVID-19 funding clawback

White House and House Republican negotiators agreed to claw back as much as $30 billion in unspent funds from six COVID-19 programs passed by Congress. The estimate is based on the broadly similar House bill.

Some of these funds were allocated to various agencies, while others have already been distributed to states and even to local governments. The actual amount recovered will likely be less than estimated because funds continue to be spent and will take a while to recover.

5. No government shutdown

Negotiators included a provision that would ensure there isn’t another fiscal crisis when Congress must pass 12 appropriations bills by October to keep the government funded into the next fiscal year. I think this is the most important component of the deal.

It automatically funds everything at 99% of the previous year’s level if Congress fails to pass the bills in time. Besides eliminating the possibility of a shutdown over the budget, as the U.S. has experienced in the past, the 1% decrease in funding provides a strong incentive for Republicans and Democrats to negotiate a compromise that keeps their priorities fully funded.

The bottom line

The deal would limit some spending in the short run but does very little to tackle America’s long-term debt problem, which I believe urgently needs to be addressed.

The U.S. national debt has exploded, most recently as a result of trillions of dollars in spending related to the COVID-19 pandemic. At a little under $32 trillion, it’s over 120% of gross domestic product, which is considered unsustainably high and is costing well over half a trillion dollars in annual interest payments. At some point, investors may begin to see U.S. government bonds as a risky investment and stop buying, which would lead to higher borrowing costs and could bring down the entire U.S. financial system.

But using the debt ceiling as a negotiating tactic is unlikely to achieve the kinds of tough choices needed to meaningfully slow the growing mountain of U.S. debt.

About 60% of total government spending goes to fund just a few items, such as Social Security, Medicare and national defense, that are very hard, politically, to cut. And political realities make it nearly impossible to increase taxes.

But a budgeting process known as reconciliation was created specifically for this purpose because it allows Congress to cut any mandatory spending and entitlement program and increase taxes in one bill. It also can’t be filibustered in the Senate – it just needs a majority.

To truly address the debt problem, what is needed, in my view, is a balanced bipartisan proposal that includes cuts to all programs, as well as some significant tax increases. Political brinkmanship won’t get America there.

For all the debt ceiling drama and the risks of profound economic damage and global tensions that resulted from it, Republicans achieved only a two-year cap on a small fraction of the total budget. Reconciliation – and lawmakers willing to govern and compromise – is a far superior way to attain a comprehensive deficit-reduction plan.![]()

Raymond Scheppach, Professor of Public Policy, University of Virginia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.