Why the Great Plains has such epic weather

Russ Schumacher, Colorado State University

From 78 degrees on Tuesday to snow on Wednesday? Swings like this aren’t unusual in the central United States, where weather can quickly shift from one extreme to another. That’s especially true in the springtime, when conditions turn into a roller coaster, with balmy spring days followed by abrupt returns to winter.

These wild swings have been on full display this spring, with a record-setting cyclone on March 13-14 and a second system this month bringing very heavy snow and intense winds to a broad area from Colorado to Minnesota. For researchers like me, this region is a fascinating, and sometimes frustrating, place to study weather and climate. It’s no accident that places like Colorado and Oklahoma are among the world’s hubs for atmospheric science.

Where the winds meet the mountains

What generates such “big weather” on the Great Plains? It starts with geography.

As you travel west across the central United States, the Plains gradually slope upward. Then, in central Colorado, the terrain quickly rises into the Rocky Mountains, creating big changes in elevation, along with more subtle ridges and river valleys. This topography sets the stage for our region’s complex weather systems.

Southeastern Colorado and the bordering panhandles of Texas and Oklahoma form a breeding ground for extratropical cyclones – the large, low-pressure systems that routinely move across the country, bringing rain, snow, thunderstorms and strong winds. As troughs of low pressure aloft move from west to east over the Rocky Mountains and then emerge on the other side, the columns of air are “stretched” vertically. This makes them spin at increasing rates, just as figure skaters do when they draw their arms in.

These features interact with the usual south-to-north gradient in temperature that exists east of the mountains – that is, warmer in the south and colder in the north – kicking off a process in which strong cold and warm fronts develop, and a cyclone can rapidly intensify. Along those fronts, widespread precipitation forms, including everything from heavy snow to severe thunderstorms.

So the day or two before the cyclone develops, temperatures are often well above average, only to quickly plummet as the strong cold front associated with the cyclone blasts through. In other words, the rapid changes in temperature that we see east of the Rockies are not just an interesting aspect of these storms – they are key to their development and intensification.

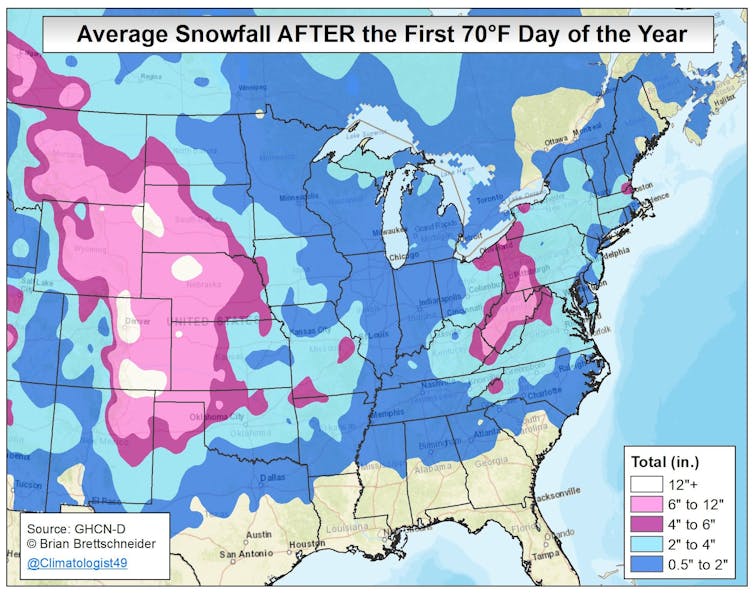

When these cyclones develop in the fall and spring, they can generate many forms of unusual and hazardous weather, sometimes just a few counties apart. Visitors in eastern Colorado are often surprised to hear warnings for wildfires, tornadoes and a blizzard at the same time. As climatologist Brian Brettschneider has shown, much of the Great Plains region averages well over a foot of snow – after the first day 70-degree day of the year! And Colorado is the only state in the nation where every month of the year is the average wettest month of the year in some part of the state.

Forecasting challenges

There is much at stake during major storms in the central U.S. This region has a history of deadly flooding, and droughts, wildfires, tornadoes and hailstorms here can cause billions of dollars in losses and damage.

Thanks to dedicated research and increasing computer power, weather forecasts continue to improve steadily. The National Weather Service’s forecasts for this year’s March and April cyclones were spot-on. But forecasting more localized snowstorms and thunderstorms is still very challenging given this region’s complex terrain. This is a subject of continued research.

There also remain important questions about the effects of climate change on the northern and southern Great Plains, thanks to the huge variability in the weather. We have seen a clear warming trend, as in most parts of the nation, but it is hard to pin down how this warming is influencing factors such as droughts, severe weather and snowstorms.

After severe droughts in many areas in 2018, 2019 thus far has been one of the wettest years on record. Is this just a reflection of our naturally highly variable climate, or part of a long-term trend associated with the overall warming of the planet?

Despite these challenges, meteorologists and climatologists are passionate about figuring out how the atmosphere works, making better predictions of its behavior and communicating that information to decision makers and the public. Events like this spring’s major storms remind us that we all need to be weather-ready, year-round.![]()

Russ Schumacher, Associate Professor of Atmospheric Science and Colorado State Climatologist, Colorado State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.