Why the southern US is prone to December tornadoes

Alisa Hass, Middle Tennessee State University and Kelsey Ellis, University of Tennessee

On the night of Dec. 10-11, 2021, an outbreak of powerful tornadoes tore through parts of Arkansas, Mississippi, Missouri, Kentucky, Tennessee and Illinois, killing dozens of people and leaving wreckage over hundreds of miles. Hazard climatologists Alisa Hass and Kelsey Ellis explain the conditions that generated this event – including what may be the first “quad-state tornado” in the U.S. – and why the Southeast is vulnerable to these disasters year-round, especially at night.

What factors came together to cause such a huge outbreak?

On Dec. 10, a powerful storm system approached the central U.S. from the west. While the system brought heavy snow and slick conditions to the colder West and northern Midwest, the South was enjoying near-record breaking warmth, courtesy of warm, moist air flowing north from the Gulf of Mexico.

The storm system ushered in cold, dense air to the region, which interacted with the warm air, creating unstable atmospheric conditions. When warm and cold air masses collide, less dense warm air rises upward into cooler levels of the atmosphere. As this warm air cools, the moisture that it contains condenses into clouds and can form storms.

When this instability combines with significant wind shear – winds shifting in direction and speed at different heights in the atmosphere – it can create an ideal setup for strong rotating storms to occur.

On a tornado ranking scale, how intense was this event?

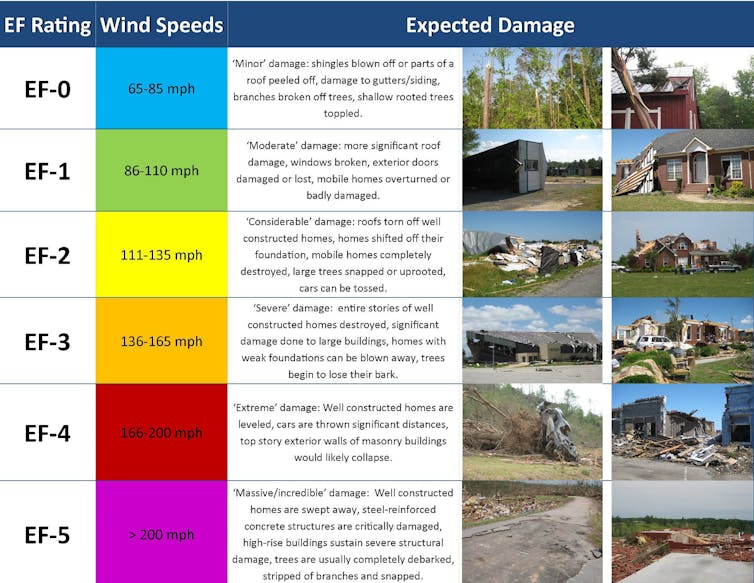

At least 38 tornadoes have been reported in six states during this outbreak, causing widespread power outages, damage and fatalities. The National Weather Service rates tornadoes based on the intensity of damage using 28 damage indicators from the Enhanced Fujita, or EF, scale. Storm assessments and tornado ratings can take several days or longer to complete.

As of Dec. 12, at least four EF-3 and five EF-2 tornadoes have been confirmed. EF-2 and EF-3 tornadoes are considered strong, with wind speeds of 113-157 mph and 158-206 mph respectively.

Strong straight-line winds also occur with severe storms and can create as much damage as a tornado. After severe storms and reports of tornadoes, the National Weather Service conducts in-person storm damage surveys to determine whether a tornado or straight-line winds created the reported damage and the degree of damage. Investigators will look to see if debris is scattered in one direction, which would indicate straight-line winds, or in many different directions – the hallmark of a tornado.

One tornado reportedly traveled 240 miles across four states. Why is this unusual?

Most tornadoes stay on the ground for a short amount of time and travel short distances – 3-4 miles on average. Long-track and very long-track tornadoes – those that travel at least 25 and 100 miles respectively – are relatively uncommon. They account for less than 1% of all tornadoes in the United States.

Long-track tornadoes require a very specific set of ingredients that must exist across a wide area. These uncommon tornadoes form from a single supercell storm – a storm with a rotating updraft called a mesocyclone – that can persist for hours.

Significant tornadoes often stay on the ground longer than weaker tornadoes. Their tracks are especially long in the Southeast, where significant tornadoes in the cool season move quickly, thus covering more ground.

The previous record for a long-track tornado was from 1925, when the F-5 Tri-State Tornado traveled 219 miles through Missouri, Illinois and Indiana. The “Quad-State Tornado,” as this tornado has been nicknamed, is expected to break that record. In the coming days, the National Weather Service will confirm whether one tornado stayed on the ground for more than 200 miles or multiple tornadoes resulted from the same storm. The agency has issued a preliminary rating of EF-3 or greater for this event.

Why do more nighttime and winter tornadoes occur in the Southeast than in other regions?

Spring is typically considered tornado season, but tornadoes can occur at any time throughout the year. The Southeast experiences a second peak in tornadic activity in the fall and early winter, and winter tornadoes are not uncommon.

Similarly, tornadoes can happen at any time of the day. Nighttime tornado events are especially common in the Southeast, where the ingredients for storms are different and more conducive to nocturnal tornadoes than in “Tornado Alley” in the Great Plains.

Tornadic storms in the Southeast are often powered by an abundance of wind shear. They do not rely as heavily on rising warm, humid air that creates atmospheric instability – conditions that require daytime heating of the earth’s surface and are more prevalent in the spring.

Forecasting for this event was accurate and predicted a major outbreak several days in advance. The National Weather Service’s Storm Prediction Center in Norman, Oklahoma, and the affected National Weather Service local Weather Forecast Offices issued timely watches, warnings and information on how to stay safe.

But nighttime tornadoes can be especially deadly. More fatalities tend to occur because people often don’t receive warning communications when they are sleeping. Storm spotting is more difficult in the dark, and people are more likely to be in more vulnerable housing, such as mobile homes, at night than during the day when they are at work in sturdier buildings.

Having multiple reliable methods for receiving warnings at night is critical, since power can go out and cellphone service can go down during severe weather. Unfortunately, during the Dec. 10-11 event, some people who went to shelters were killed when tornadoes struck the building they were in. But timely warnings that allow people to shelter safely in a solid structure tied to a foundation or basement can mean survival during less-devastating events.

[Too busy to read another daily email? Get one of The Conversation’s curated weekly newsletters.]![]()

Alisa Hass, Assistant Professor of Geography, Middle Tennessee State University and Kelsey Ellis, Associate Professor of Geography, University of Tennessee

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.