Why tiny schools like Karval in Colorado are going underground

© iStock

Liberty High School has a proud heritage associated with basketball, but no active basketball team. It does have a gymnasium, though.

That gymnasium, which is located on Colorado’s plains east of Denver, was flooded with water in January 2024 when aging copper coils associated with natural gas heating ruptured. School district officials decided their money was best spent on a new heating and cooling system that taps the relatively constant year-round temperature 500 feet below ground.

Year-round temperatures at that depth fluctuate between 55 and 60 degrees. Ground-source heat pumps deliver air inside buildings at 68 or 74 degrees, the comfort level for most people. On a hot summer day, when the temperature outside is 100 degrees, the same technology can deliver cooler air. The technology uses principles similar to those of a refrigerator's compressor to keep leftover dinners cool.

The geothermal technology — variously called geo-exchange and ground-source heat pumps — has been rapidly gaining favor in schools and other public buildings in Colorado during the last 25 years. Poudre Valley, a school district based in Fort Collins, installed geo-exchange for an administrative building in 2002 and recently in several new buildings.

© flickrcc - Alan Levine

Most ambitiously, Colorado Mesa University, in Grand Junction, embarked on a geo-exchange system in 2008 that now includes 16 buildings. University officials there identify the 2.5 miles of coils buried below soccer fields and other places being a key reason they have been able to save $1.5 million annually in utility costs. This, in turn, allows them to offer the third-lowest combined tuition and fee rate among Colorado’s 12 public colleges and universities.

Now, with the aid of $12 million in grants scattered across Colorado in the last two years, adoption of the technology has been accelerating in both cities and small towns — and in some schools, too.

Getting to the Liberty school requires driving on Highway 36, the same highway that splices Boulder and Estes Park on its way across Rocky Mountain National Park. East of Denver, the highway traverses 140 miles across undulating and sparsely populated landscapes before descending to Joes, population 82.

Just beyond Joes lies Liberty's K-12 school. The parking lot has an American flag painted over one space. Another parking space has the title of a 2023 country song: "Try That in a Small Town."

Erected in 1966, the building houses all students in the district. This year Liberty had a single graduating senior. Two more will graduate next year and 10 or 11 the year after. Total district enrollment this fall was 80. For two decades, it has had a 100 percent graduation rate.

Joes is a footnote in basketball history. In 1929, when basketball was still in its relative infancy and the world was stumbling into the Great Depression, a team from Joes High School bested all the other basketball teams from Colorado high schools.

The Joes team then went to a national tournament in Chicago hosted by the famous coach Amos Alonzo Stagg. There, in the national tournament, the boys from Joes placed third. They were bestowed with three basketballs to commemorate the accomplishment, as was recounted in "The Boys from Joes," a 1987 book by Nell Brown Propst. Now deflated, the balls can be seen in a showcase outside the gymnasium that was flooded.

The gymnasium gleams with a polished wooden floor. Banners of six-man football and other athletic achievements of decades past drape the walls. On one side is a stage, "Home of the Liberty Knights," and on the other, bleachers. They still get filled at times, but not necessarily for sporting events. Many funerals are held at the gym, as no local churches can accommodate larger crowds.

Rhonda Puckett, the school district superintendent who doubles as principal of the schools, says the flooding occurred at a good time, if there could be one. The building was still occupied. Teachers and others grabbed towels, art-class T-shirts and whatever they could find to mop up the water. No permanent damage occurred.

That crisis also left Puckett with an opportunity. The 36,000-square-foot building was structurally sound but deficient in other ways. Window air conditioners kept the classrooms so-so but not the building's interior spaces. During winter, the cafeteria was cold enough to require jackets.

Millig Design Build, a Centennial-based company, responded to the school district’s call for ideas.

Aaron Tilden, a mechanical engineer who was assigned to work with Liberty, had already worked with many rural school districts in Colorado and Kansas. He declares himself no purist. He always looks at the options through the lens of long-term costs and human benefits.

The economics of schools, even small ones, can differ from those of homes or even office buildings because schools must heat or cool air from the outside frequently to maintain adequate indoor air quality. Think about the needs of a 20- by 20-foot classroom, with 25 students and a teacher in it, he says.

"A 35,000-square-foot office building probably needs a quarter as much outdoor air as a 35,000-square-foot school."

Air-source heat pumps have soared in popularity in Colorado and elsewhere. They can be quite effective in homes, even in colder mountain towns. And in some specific circumstances, they can work in schools. For example, Millig installed an air source system at a school in Akron, also on Colorado's eastern plains.

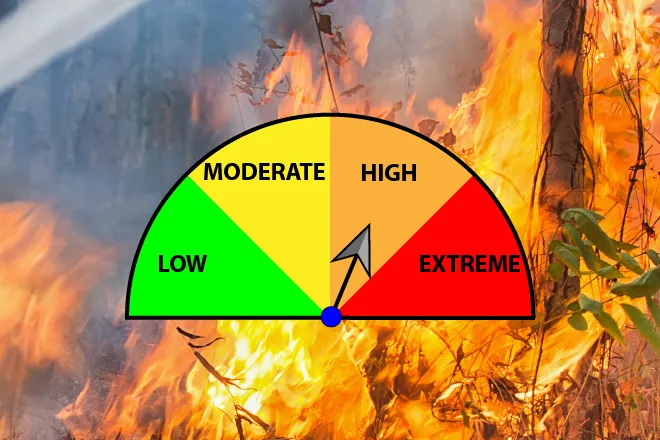

Tilden sees ground-source heat pumps being superior to many alternatives. One school in Kansas was closed for several days because its air-source heat pumps, afflicted by ice buildup and high winds, were insufficient.

"I have 100 percent confidence with ground-source heat pumps providing heat no matter what is going on outside," says Tilden. "I am less confident in recommending that an air source pump can provide heat duringthose very cold, very windy and icy days."

Ground-source heat pumps do have a problem for buildings used almost exclusively for heating. Over time, the available heat underground can diminish.

Ground-source systems work most effectively when used both for heating and cooling. At Colorado Mesa, for example, the diversity of buildings and their uses allow maintenance of this thermal balance. And for that matter, with schools now opening in early to mid-August, they also need to be cooled.

For Liberty, Tilden recommended a ground-source system coupled with a backup boiler fueled by natural gas. The gas boiler is expected to be used less than 10 percent of the time.

Northern Colorado's Poudre School District may have been the first school district to give this geothermal a try. That was in 2002, a few years after the district began exploring energy and cost-efficient designs for new buildings. The pilot was at an operations building.

Eleven years later, Stu Reeve, then the energy manager for the district, estimated that the geothermal heat-pump-driven system had required 50 percent less energy. It needs more electricity but no natural gas.

Unlike some places, Poudre does have natural gas available for the buildings in case the geo-exchange systems go down. So far, they have not.

Poudre in 2004 used geo-exchange again at Kinard Core Knowledge Middle School in Fort Collins. Recently, it has used the technology at an elementary school in Loveland; a middle school in Timnath; and the middle-high school in Wellington.

"It is very energy efficient technology," said Trudy Trimbath, the district's energy and sustainability manager. She reports little fluctuation in energy use related to extreme changes in weather as compared with a traditional mechanical cooling system. It also provides even heating throughout the buildings.

Up-front costs of geo-exchange systems typically pose the single largest barrier to adoption of the technology. It depends on whether the geo-exchange is designed for a new or existing building. It also depends upon the available land.

Geo-exchange will cost more up front than natural gas in any situation, but in a new building, says Erik Jeannette, director of engineering at Denver-based Iconergy, the extra costs of the $2 million to $5 million well field can be recovered within a decade because of lower fuel costs. He has designed geo-exchange systems for about 12 schools around Colorado.

Simplified designs have narrowed up-front cost differences. A design team working on a new community building in Fort Collins recently concluded that a geo-exchange system would cost only slightly more than alternatives.

Colorado now has several dozen schools, most in rural areas, with geothermal heating and cooling. A few have had problems, but Jeannette believes those problems were caused by flawed initial designs. He believes the technology has become far easier to deploy.

Retrofitting existing buildings to use geo-exchange can be far more difficult. Ground-source technology should always be evaluated, although rarely does replacement of boilers and chillers justify the added costs.

In small school districts, state grants have made all the difference. That was true at Liberty. It is also true at the Karval School District, which this year has 30 students from pre-kindergarten through 12.

Karval lies in one of Colorado's most sparsely populated areas. Located 80 miles east of Colorado Springs, the school is 10 miles away from a state highway by way of county roads. If school is dismissed for snow, older students will likely be out on horseback rounding up cattle.

"Everybody has plenty of elbow room here," says Sarah Nuss, a graduate of the school and now the district superintendent.

©

In late July, a test bore was drilled for a geo-exchange well field that is to come in early 2026. As with Liberty,the building itself is structurally sound. It needs updated electrical systems, so a breaker doesn't get tripped when plugging in a computer, says Nuss.

For this geo-exchange work the Colorado Energy Office awarded Karval nearly $500,000. Another $3.5 million was delivered by the Colorado Department of Education's Building Excellent Schools Today program. Grants will pay nearly 100 percent of the upgrades.

Grants were also crucial to Liberty's geothermal work. The Liberty district has a thin property tax base consisting almost entirely of farms, many of them dryland. It lacks even a giant dairy or feedlot. Crucial has been the $1.865 million in state grants, the most recent from the Colorado Energy Office in April. Total project costs are $5.4 million.

Tilden says that without the grants it's very unlikely Liberty would have had a business case for the ground-source system.

Drilling of the 25 wells began in late July, two weeks before classes resumed Aug. 13. The 500-foot holes lie about 20 feet apart. They are connected by loops in two trenches that are about five feet deep. The system has about five miles of piping. A house heated and cooled by geothermal may need only one or two wells.

School districts have various motivations. The Fort Collins-based school district has energy goals of being good community stewards and protective of natural resources while being fiscally prudent. "The two go hand in hand," says Poudre's Trimbath of the ground-source heat pumps and the district policy.

The Liberty school board was aware that geothermal heat pumps will have far fewer emissions. But that did not drive the approval.

"It really was not anything about emissions," says Puckett, Liberty's superintendent. "It was about options, doing something that would be sustainable for a long time for us."

A standardized metric of a building's energy consumption relative to its size is called energy use intensity, or EUI. Typically, the lower the EUI, the more efficient the building is .

Energize Denver, in its evaluation of 127 Denver school buildings, found almost two dozen secondary schools above 80 and the majority from 41 to 80. Only 17 scored 40 or less. At Liberty, using a variety of energy efficiency tools, Tilden aims to deliver an EUI of less than 20 once the project is completed this autumn.

As for new buildings, Tilden agrees that geo-exchange always represents a viable option. Sadly, he says, it has sometimes been rejected in favor of architectural niceties.

"New construction projects are often led by architects that sometime prioritize construction dollars for architectural features rather than spending additional dollars on the mechanical systems," he says. "We have seen buildings with grand entryways, fancy lighting and expensive construction materials in lieu of high-efficiency heating and cooling systems that will benefit owners for many years to come.”

As for Liberty, it may never again have enough students to field a basketball team, let alone one capable of besting all others in Colorado. Soon, though, it will have classrooms, hallways and a cafeteria comfortable in all seasons.