Bison are back, and that benefits many other species on the Great Plains

Matthew D. Moran, Hendrix College

Driving north of Pawhuska, Oklahoma, an extraordinary landscape comes into view. Trees disappear and an immense landscape of grass emerges, undulating in the wind like a great, green ocean.

This is the Flint Hills. For over a century it has been cattle country, a place where cows grow fat on nutritious grasses. More recently, a piece of this landscape was transformed in 1992 when the nonprofit Nature Conservancy bought the Barnard Ranch. It created a nature reserve there, the Tallgrass Prairie Preserve, which now covers almost 40,000 acres.

A central element of the group’s conservation strategy was reintroducing the American bison (Bison bison), which had been eradicated from the land in the mid-1800s. Releasing the first bison in 1993 was a step toward restoring part of an ecosystem that once stretched from Texas to Minnesota.

Today some 500,000 bison have been restored in over 6,000 locations, including public lands, private ranches and Native American lands. As they return, researchers like me are gaining insights into their substantial ecological and conservation value.

Near extinction

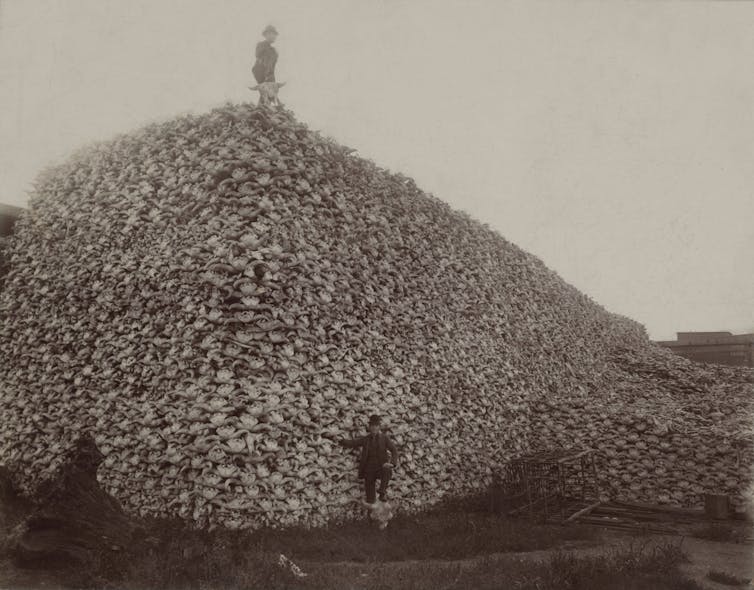

It was not always certain that bison could rebound. Once numbering in the tens of millions, they dominated the Great Plains landscape until the late 1800s, anchoring a remarkable ecosystem that contained perhaps the greatest concentration of mammals on Earth. That abundance was wiped out as settlers and the U.S. government engaged in a brutally effective campaign to eradicate the ecosystem and the native cultures that relied on it.

Bison were shot by the millions, sometimes for “sport,” sometimes for profit, and ultimately to deprive Native Americans of vital resources. By 1890 fewer than 1,000 bison were left, and the outlook for them was bleak. Two small wild populations remained, in Yellowstone National Park and northern Alberta, Canada; and a few individuals survived in zoos and on private ranches.

Recovery

Remarkably, a movement developed to save the bison and ultimately became a conservation success story. Some former bison hunters, including prominent figures like William “Buffalo Bill” Cody and future President Theodore Roosevelt, gathered the few surviving animals, promoted captive breeding and eventually reintroduced them to the natural landscape.

With the establishment of additional populations on public and private lands across the Great Plains, the species was saved from immediate extinction. By 1920 it numbered about 12,000.

Bison remained out of sight and out of mind for most Americans over the next half-century, but in the 1960s diverse groups began to consider the species’ place on the landscape. Native Americans wanted bison back on their ancestral lands. Conservationists wanted to restore parts of the Plains ecosystems. And ranchers started to view bison as an alternative to cattle production.

More ranches began raising bison, and Native American tribes started their own herds. Federal, state, tribal and private organizations established new conservation areas focusing in part on bison restoration, a process that continues today in locations such as the Tallgrass Prairie National Preserve in Kansas and the Fort Peck Reservation in Montana.

By the early 2000s, the total North American population had expanded to 500,000, with about 90 percent being raised as livestock – but often in relatively natural conditions – and the rest in public parks and preserves. For scientists, this process has been an opportunity to learn how bison interact with their habitat.

Improving prairie landscapes

Bison feed almost exclusively on grasses, which, because they grow rapidly, tend to out-compete other plants. Bison’s selective grazing behavior produces higher biodiversity because it helps plants that normally are dominated by grasses to coexist.

Because they tend to graze intensively on recently burned zones and leave other areas relatively untouched, bison create a diverse mosaic of habitats. They also like to move, spreading their impacts over large areas. The variety they produce is key to the survival of imperiled species such as the greater prairie chicken (Tympanuchus cupido) that prefer to use different patches for different behaviors, such as mating and nesting.

Bison impacts don’t stop there. They often kill woody vegetation by rubbing their bodies and horns on it. And by digesting vegetation and excreting their waste across large areas, they spread nutrients over the landscape. This can produce higher-quality vegetation that benefits other animals.

Studies, including my own research, have shown that bison-induced changes in vegetation composition and quality grazing can increase the abundance and diversity of birds and insects in tallgrass prairies. Bison also affect their environment by wallowing – rolling on the ground repeatedly to avoid biting insects and shed loose fur. This creates long-lasting depressions that further enhance plant and insect diversity, because they are good habitats for plant and animal species that are not found in open areas of the prairie. In contrast, cattle do not wallow, so they do not provide these benefits.

It is hard to determine the ecological role that bison played before North America was settled by Europeans, but available evidence suggests they may have been the most impactful animal on the Plains – potentially a keystone species whose presence played a unique and crucial role in the ecology of prairies.

The growth of bison ranching

The return of the bison has generated a new industry on the Plains. The National Bison Association promotes these animals as long-lived, hardy and high-quality livestock. The group hopes to double bison numbers through its Bison 1 Million commitment, a program designed to increase interest in bison ranching and consumption.

Advocates cite health, ecological and ethical arguments in support of bison ranching. Bison meat is lean and has a high protein content. Many bison ranchers are committed to ethical and sustainable ranching practices, which sometimes are lacking in modern industrial livestock farming.

“I have a love of nature and want to protect it. It was one of my family’s goals to restore the grasslands. Bison helped us regenerate the land,” Mimi Hillenbrand, owner and operator of the 777 Bison Ranch near Rapid City, South Dakota told me. She adds, “I love the animal. We are lucky that we brought them back. I learn every day from them.”

Thinking bigger

Will bison live on in relatively small, isolated herds as they do now, or something greater? The American Prairie Reserve, a Montana-based nonprofit, has a big and controversial idea: creating an ecologically functioning 3 million acre preserve of private, public and tribal lands in northeast Montana, with a herd of over 10,000 bison – the largest single population in the world. Although this would be small compared to the millions that once existed, it still would be something to see.

Bison were saved through the combined efforts of conservationists, scientists, ranchers and ultimately the general public. As their comeback continues, I believe that they can teach us how to be better stewards of the land and provide a future for the Plains where ecosystems and human cultures thrive.![]()

Matthew D. Moran, Professor of Biology, Hendrix College

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.