Cameras in the court: Why most Trump trials won’t be televised

David Cuillier, University of Florida

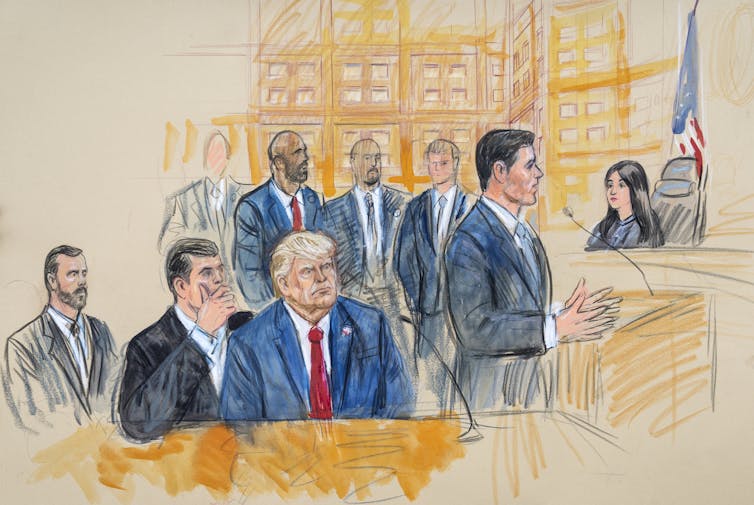

Americans will have few opportunities to binge-watch the Donald J. Trump trials.

It is unlikely the four court proceedings facing the former president will be televised live, with the exception of the case in Georgia, which favors public transparency under a policy established for that state’s courts known as Rule 22.

The near blackout will leave 330 million Americans relying on news reports, artist renderings and social media posts for the bulk of their information, despite wanting to see the live proceedings for themselves.

A Quinnipiac University poll released Aug. 16, 2023, indicates that 71% of Americans support television coverage of Trump’s “trial related to his attempting to overturn the results of the 2020 presidential election.” A June poll found that 64% support televising proceedings regarding Trump’s handling of classified documents. Even members of Congress from both sides of the aisle proposed legislation requiring cameras in the U.S. Supreme Court.

After all, courtroom cameras are allowed in nearly all state courts, along with the 9th and 2nd U.S. Circuit Courts of Appeals, which cover cases from the West Coast and the Northeast states of New York, Connecticut and Vermont. In this age of Court TV and Judge Judy, why would trials not be televised?

As director of the Brechner Freedom of Information Project at the University of Florida, I get that question a lot. Our center, for nearly 50 years, has researched the public’s ability to access civic data critical for self-governance.

There are many reasons why all trials aren’t televised, spanning the history of case law, congressional legislation, empirical research, high-profile “circus” trials and, in some cases, fear.

From public to pensive

The right to a public trial is enshrined in English common law and the Sixth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Almost everyone is guaranteed public access to, and thus oversight of, their case, which allows the public to hold the system accountable.

But the courts have struggled to define how “public” to make a public trial.

In 1807, former Vice President Aaron Burr was tried for treason in Richmond, Virginia, drawing reporters from throughout the country for what was called the “Trial of the Century.” While newspapers published inflammatory articles against Burr, Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall determined that the negative pretrial publicity did not prejudice the jury or damage the sanctity of the court.

Technology, over time, would change that thinking.

The 1925 Scopes “Monkey Trial,” in which a teacher was accused of illegally teaching evolution, was the first to be covered on live radio and integrate electronic technology. Cameras documented the 1935 trial of Bruno Hauptmann for the kidnapping and killing of Charles Lindbergh’s son, resulting in what some described as a “media circus.”

In response, the American Bar Association adopted Canon 35, banning photographers and microphones from the courtroom to protect the “essential dignity” of proceedings. In 1946, Congress enacted the Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 53, prohibiting cameras and broadcasters from federal criminal trials, but not for state courts.

Oklahoma, Colorado, Texas and other states began allowing TV cameras in court, which was deemed constitutional in 1981 by the Supreme Court in Chandler v. Florida, although the high court would not permit cameras in its own proceedings. Generally, in most state courts, an individual judge can make the ultimate decision about allowing cameras in their courtroom.

Court TV debuted in 1991, and the O.J. Simpson murder trial in 1995 sparked widespread criticism of televised proceedings, which continues to resonate today. Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts said in 2018 that with cameras allowed in the high court, “I think, frankly, some of my colleagues would act differently, and that would affect what we think is a very important and well-functioning part of the decision process.”

Grandstanding or transparency?

Some argue that televising the Trump trials would encourage his team to employ courtroom theatrics to build public support for reelection. A lawyer representing Trump in the federal 2020 election case said in July that he would prefer cameras in the courtroom.

Judges say cameras invite grandstanding by lawyers, intimidate jurors and witnesses, or cause select sound bites to reflect poorly on the court. Indeed, a recent experiment found that people watching videos of judges arguing with lawyers were less supportive of judges than when they witnessed neutral exchanges between the two parties.

Even camera angles can affect perceptions – one experiment showed that when jurors saw video of a suspect confessing, they were more likely to ascribe guilt if the video showed just the suspect, excluding the interrogator.

Introduce the possibility of using artificial intelligence to create deepfake videos about courtroom proceedings, and judges may get even more skittish.

On the other hand, official recorded court proceedings could counter misinformation. Transparent trials shed light on the truth and have “significant community therapeutic value,” as then-Supreme Chief Justice Warren Burger wrote in 1980 in Richmond Newspapers v. Virginia, a case that guaranteed the media’s right to attend criminal trials.

Televising trials could lead to greater public understanding of the legal system, at a time when only 47% of Americans can name all three branches of government. Trust in the federal courts has dropped to its lowest point in 50 years, and trust in the Supreme Court, specifically, continues to plummet.

Providing more information to the public increases trust in institutions. One study indicates that recording trials can actually help train better lawyers by viewing, not just reading about, previous cases.

A 1994 Federal Judicial Center study found that judges and lawyers noted little-to-no detrimental effect of cameras on federal proceedings. Witnesses said they weren’t distracted by cameras, and jurors said TV coverage did not affect their judgment.

If anything, some assert that cameras can improve performance and behavior of participants because of the extra scrutiny, and one study indicated that live blogging from trials improves professionalism of lawyers and judges. Televising federal trials wouldn’t be unusual – Canada, England and Brazil televise theirs.

Given the significance of the Trump trials, some say the rules should be changed quickly to ensure the public sees firsthand what transpires, even if just for history’s sake. That would require an act of Congress and a rule change by the Judicial Conference, which makes policy for U.S. courts.

Perhaps a televised trial in Georgia will put the issue to the test by serving as a comparison, or experiment, of sorts. In the future, the United States may continue to move toward cameras in all courts, including the Supreme Court, through audio recordings, posting of transcripts, releasing video after the proceedings, and well-controlled courtroom decorum – until they begin streaming justice live, routinely, and for all.![]()

David Cuillier, Director of the Brechner Freedom of Information Project, College of Journalism and Communications, University of Florida

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.