Colorado low emission vehicle regulations face scrutiny from think tank

By Derek Draplin | The Center Square

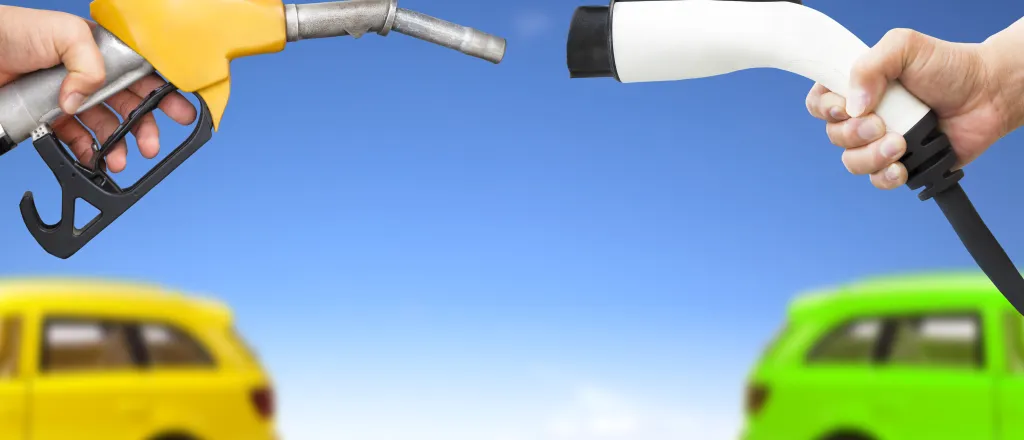

Colorado’s low emission vehicle standards are facing new scrutiny ahead of a state commission meeting where stricter mandates will be decided.

The California-based Pacific Research Institute released a policy paper last month criticizing an initial economic analysis (IEIA) on the Colorado Low Emission Automobile Regulations, known as CLEAR.

CLEAR, approved in 2018 under former Governor John Hickenlooper, imposes parts of the California low emission vehicle (LEV) standards in Colorado. Current Gov. Jared Polis took measures a step further, signing an executive order requiring the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (CDPHE) to develop a zero emission vehicle (ZEV) program to be proposed to the Colorado Air Quality Control Commission (AQCC).

The ZEV regulations were proposed as an amendment to CLEAR, and will be considered by AQCC at a rule-making hearing next week.

As the state considers the mandate, those in the automobile industry have warmed to the California standards. Last week the Alliance of Automobile Manufacturers and Global Automakers, along with state government divisions, agreed to submit a ZEV regulatory proposal to the AQCC, a plan separate from the ZEV proposal the commission is slated to consider.

An initial economic impact analysis (IEIA) was conducted in May “to assess the additional costs and benefits of adopting the proposed ZEV requirements in addition to the low emission vehicle requirements … in CLEAR.”

The IEIA found that the program would have environmental benefits by reducing vehicle emissions, estimating a reduction of 2.2 million metric tons in emissions waste by 2020.

“Greenhouse gas emission benefits from a ZEV program would principally be in the form of carbon dioxide emission reductions from vehicle tailpipes and some associated methane emission reductions from power plants and refineries,” the analysis said.

For consumers, the state analysis predicted that the average cost of new battery electric vehicles (BEV) would decrease from over $34,000 in 2023 to $26,000 in 2030, and the average cost of new plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEV) would go from over $34,000 in 2023 to $33,500 in 2030, while the average cost of new conventional fuel vehicles are projected to increase from $27,900 in 2023 to $28,600 in 2030.

The analysis also said PHEVs and BEVs are more power-efficient and offered “significant operational and maintenance savings” compared to conventional fuel vehicles.

It also added that the program would impact vehicle manufacturers and dealers who would have to comply with the new requirements, but would not “affect the ability of manufacturers to continue to manufacture and market conventional vehicles of all types.”

“Some new vehicle dealers may be under pressure from manufacturers’ obligations to meet ZEV sales requirements,” the analysis said.

“Fuel refiners, jobbers, and marketers would presumably be affected by reduced demand for gasoline,” the analysis said, noting increased population in the state should “offset any loss in gasoline sales in the near future.”

But a critical analysis of the IEIA by Dr. Wayne Winegarden of the Pacific Research Institute, a free-market think tank, said state officials are painting a rosy picture of the regulations, which he argued “would impose higher economic costs on poor and working-class communities,” something the state analysis doesn’t consider.

“Colorado officials are painting a rosy scenario of how the low emission vehicle standards will impact the economy and the environment, but taxpayers should beware,” Winegarden said. “Taking a realistic look shows that CLEAR could impose much higher costs on poor, minority, and rural communities – without achieving promised emission reductions. Instead of adopting CLEAR, state government would be wise to embrace proven, free-market reforms that have successfully lowered emissions without hurting the economy.”

Winegarden said in the brief that the state analysis also doesn’t consider several other points, including that emissions in Colorado are already falling despite CLEAR, and the proposed regulations would only shift emissions to other locations like China, where many electric vehicles are produced.

More electric vehicles could also burden an electrical grid not prepared for a shift to electric vehicles, Winegarden said.

“EVs shift the power source for vehicles to the electric grid, which will create a significant increase in the demand for electricity,” he wrote. “As a result, Colorado’s electricity transformation needs to not only insure that current electricity demand projections are met, the transformation needs to ensure that an unknown surge in demand is also met.”

Retail electricity prices could go up as a result.

“Should Colorado adopt the California approach, it should expect energy costs in the state to rise, to the detriment of economic growth and lower-income families,” he said. “The IEIA should fully consider these impacts in its assessment.”

Winegarden also noted extreme temperatures in the state can affect electric vehicle battery performance, and therefore impact the net emissions reductions, something the state analysis doesn’t account for.

Garry Kaufman, director of the Air Pollution Control Division, which is part of the CDPHE, said the department did not review in detail the Pacific Research Institute’s brief on the IEIA, but defended the state’s analysis in an email to The Center Square. (The Air Pollution Control Division is different from the Air Quality Control Commission, which is appointed by the governor and is tasked with rule making for the state’s air quality program.)

“For the Final Economic Impact Analysis, the Department utilized the International Council on Clean Transportation for much of its analysis. ICCT is an internationally recognized leader in the field,” he said. “CDPHE is not aware of any credible information to suggest that the costs of conventional gasoline-powered vehicles will increase as a result of a ZEV program in Colorado.”

Kaufman added that the department will produce a cost benefit analysis and regulatory analysis at a later date.

Kelly Sloan, an energy and environment policy fellow at the Centennial Institute and the executive director of Freedom to Drive Coalition, which advocates for motorists in the state, argued the market isn’t yet ready for electric vehicles in the way the state government wants.

“It’s a costly, regressive regulation and the costs don’t net us any environmental benefit,” Sloan said. “And I want to make clear that I’m not against electric vehicles … but the point is, what these regulations are doing is manipulating and distorting the market, and basically trying to force a square peg into a round hole.”

“They’re trying to force these vehicles onto a market that’s not ready for them,” he added.