Colorado Parks Explores Vaccination to Protect Prairie Dogs from Plague

New research from Colorado Parks and Wildlife and its partners shows that treating prairie dog colonies annually with a flea-killing dust or an oral vaccine can prevent their complete collapse when confronted with plague.

In a three-year study conducted in northern Larimer County, dusted or vaccinated prairie dog colonies survived during plague outbreaks while nearby untreated colonies were devastated. Neither treatment was completely effective at preventing plague, but some prairie dogs did survive in the colonies treated prior to plague outbreaks.

“

Burrow dusting has been used by CPW since 2010 to protect select Gunnison’s prairie dog colonies from plague in the Gunnison Basin and elsewhere. Those efforts furthered conservation of the species sufficiently that a federal listing as threatened or endangered was deemed unnecessary. Dusting also has been used at sites scattered throughout the West in recent years to help restore the endangered black-footed ferret.

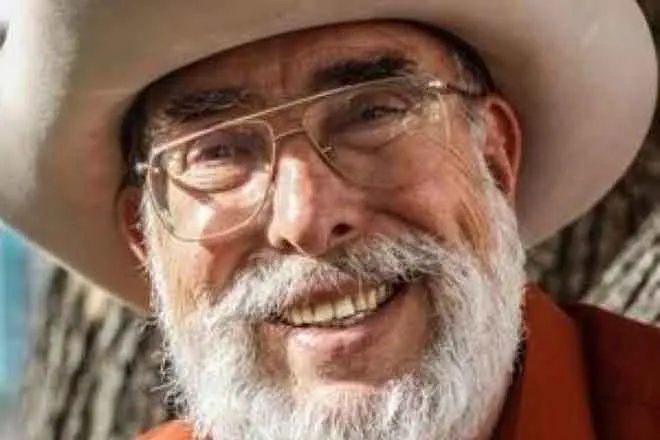

“The prairie dogs encountered them while foraging. We saw that most of the animals in a colony found and ate the baits, so they must have been a hit,” Tripp said. “After eating one of the baits, the prairie dog’s immunity to plague is boosted, so when exposed to the actual pathogen later at least some can fight off the infection and survive.”

“We certainly appreciate the collaboration with our research partners. We couldn’t have made these strides without access to field sites at Soapstone Prairie and Meadow Springs Ranch (owned by the city of Fort Collins)."

CPW partnered with the U.S. Geological Survey’s National Wildlife Health Center where researchers worked with scientists at the University of Wisconsin to develop and produce the vaccine used in these experiments.

"We're very appreciative of the work done by those scientists," Tripp said.

The results of this research will help guide management of imperiled prairie dog species and a handful of black-footed ferret recovery sites across the state.

“We were happy to host Colorado Parks and Wildlife research on plague mitigation strategies at Soapstone and Meadow Springs,” said Daylan Figgs, Natural Areas Program leader with the city of Fort Collins. “We really need these plague-management tools to support the population of black-footed ferrets that were reintroduced in 2014,” Figgs said.

Colorado’s work on field vaccine effectiveness was done in collaboration with the federal National Wildlife Health Center to evaluate the new vaccine at 29 sites in seven states across the West.

The impacts of this work go beyond simply protecting prairie dogs and black-footed ferrets from plague. Major beneficiaries of continued progress in plague mitigation for wildlife will help Colorado’s agricultural community and outdoor enthusiasts who recognize the importance of prairie dog and plague management to negate the need for further endangered species designations.

“The successful development of these plague management tools will help Colorado’s farmers and ranchers to use voluntary, incentive-based programs to conserve prairie dogs and recover the endangered black-footed ferret,” said Ken Morgan, Private Lands Program manager with CPW. “Successful plague mitigation will help to ensure that future federal endangered species listings for Colorado’s three prairie dog species will be unnecessary.”

Colorado’s landowners and wildlife managers have for decades been vexed by plague as they've tried to recover the endangered black-footed ferret and conserve prairie dog colonies which make up their primary prey.

Plague is caused by non-native bacteria transmitted by fleas. The first cases in Colorado were recorded in the 1940s. Plague has been devastating to Colorado’s wildlife, as it has become entrenched in the state. Outbreaks periodically kill vast swaths of prairie dog colonies that support a myriad of other wildlife species such as burrowing owls, badgers, insects and plant species.

“Wildlife managers have really struggled to recover ferrets and manage prairie dog colonies in Colorado because we have had no ability to mitigate the devastating effects of plague,” Tripp said. “Hopefully the development and use of these new tools in select areas and with the support of willing landowners will help to limit the impact of plague on Colorado’s wildlife.”

How best to employ these tools in a cost-efficient manner will be the focus of continuing research by Colorado Parks and Wildlife. This and future CPW plague management research is funded through the Colorado Species Conservation Trust Fund thanks to annual severance tax funding authorized by the Colorado General Assembly.