Commentary - What have we learned since the 2020 Stanley, Idaho, earthquake?

© iStock

For many years, the Sawtooth fault in central Idaho was recognized as an active fault, but it remained understudied. Then the Stanley earthquake shook much of the northwestern USA in 2020, providing dramatic confirmation of the area’s tectonic activity. The quake spurred a flurry of research that is shedding light on the Sawtooth fault, while also raising new questions about fault behavior and earthquake history in central Idaho.

The March 31, 2020, M6.5 Stanley earthquake was the second largest earthquake ever recorded in Idaho (after the 1983 M6.9 Borah Peak earthquake). Although not directly related to Yellowstone, the earthquake and its numerous aftershocks occurred in the Centennial Tectonic Belt, which has been influenced by passage of the area over the Yellowstone hotspot. This zone of seismicity wraps around the hotspot like a bow wave around a boat.

After a strong earthquake, geologists and seismologists typically work quickly to collect data that will help to better understand the event.

However, the Stanley earthquake happened early in the COVID-19 pandemic and immediately following a large snowstorm. This made it difficult for scientists to conduct field work. Despite the slow start, we have learned much in the last four years.

The Stanley earthquake was more complex than first appreciated. The location of the earthquake suggested that it was generated on the east-dipping Sawtooth normal fault. The focal mechanism, however, suggested a complex, multi-fault rupture that was neither normal nor east dipping.

At least three different models have been proposed for the geometry of the faults responsible for the Stanley earthquake, including two parallel faults, two faults crossing at an acute angle, and two perpendicular faults. Regardless of which is correct, all the models describe a complex geometry.

Aftershocks are a normal consequence of all strong tectonic earthquakes. They typically occur along the fault plane of the main shock as the crust adjusts to new stresses following the release of energy.

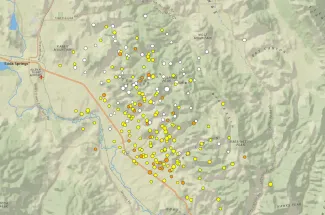

Scientists from the Idaho Geological Survey, Boise State University and the U.S. Geological Survey were able to deploy temporary seismometers to measure aftershocks around the Stanley area — aftershocks that are still occurring today (the stronger the earthquake, the longer the aftershocks persist).

Mapping aftershocks in three dimensions paints a picture of the fault plane. The Stanley aftershocks show a north-trending fault that dips steeply to the west, parallel to the Sawtooth fault but dipping in the opposite direction — yet more evidence of this earthquake’s complexity.

The earthquake did not rupture the surface, which often happens with earthquakes of M6.5 and greater. Ground deformation data and modeling suggest that the fault movement that generated the earthquake stopped at a depth of about 10.6 miles.

While there was no surface fault rupture, the Stanley earthquake did trigger many snow avalanches, debris slides and rock falls.

One of the most dramatic effects of the earthquake was liquefaction at Stanley Lake. Ground shaking can weaken loose, water-saturated sediments, causing them to behave almost like a liquid.

At Stanley Lake, the sandy area near the inlet stream sank dramatically due to liquefaction. A popular beach at the inlet stream delta completely disappeared, and large cracks and sand boils formed along the shore.

More information about this liquefaction event can be found on the Idaho Geological Survey’s website: https://www.idahogeology.org/geologic-hazards/earthquake-hazards/stanley-lake-liquefaction.

New lidar data collected shortly after the earthquake allowed geologists to map the Sawtooth fault in detail. The resulting map shows that instead of a single continuous line, the Sawtooth fault is a discontinuous fault zone with several strands.

Detailed maps of the fault allowed researchers to identify sites for paleoseismic trenching. These investigations involve digging a trench across the fault to log and date sediments that have been displaced by past earthquakes. U.S. Geological Survey geologists who excavated a trench across the northern Sawtooth fault found evidence for at least one earthquake there, approximately 9,000 years ago.

© iStock - allanswart

Additional paleoseismic trenches are planned and will help to clarify the history of earthquakes along other sections of the fault.

Researchers have also used lake records to examine the Sawtooth fault’s history. Sediment cores from Redfish Lake preserved evidence of two earthquakes (4,300 and 7,600 years ago) along the central part of the Sawtooth fault.

Lake sediment cores from Pettit Lake, 15 kilometers to the south, preserved evidence for a single earthquake about 5,100 years ago that was distinct from the earthquake events at Redfish Lake.

Geologists examine a paleoseismic trench across the Sawtooth fault in Idaho in September 2022. Trenches like this provide geologists an opportunity to date sediments that were offset by past earthquakes, thus determining the rupture history of the fault. (Zach Lifton/Idaho Geological Survey)

Despite all of these new insights into the Stanley earthquake and Sawtooth fault, many questions remain.

For example, did the entire Sawtooth fault ever rupture in a single earthquake? If not, what is the history of smaller earthquakes on shorter segments? Do earthquakes on the northern part of the fault rupture several strands simultaneously or at different times?

Field work and modeling continues as geologists work to better understand this unique and important fault system in central Idaho.

Idaho Capital Sun is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Idaho Capital Sun maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Christina Lords for questions: info@idahocapitalsun.com. Follow Idaho Capital Sun on Facebook and X.