Curious Kids: Why are moths attracted to light?

Carlos Linares, Boise State University and Jesse Barber, Boise State University

Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to curiouskidsus@theconversation.com.

Why are moths attracted to light? – Gabriel H., age 7, Providence, RI

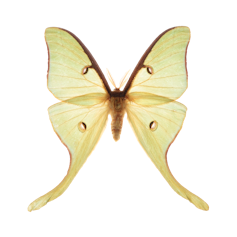

Have you ever gone for a walk at night and looked up at the lights along the street? If you paid attention, you probably saw lots of little creatures flying around those lights. Why do moths, one of many kinds of insects, fly toward light? Some circle around, others zigzag, but they all seem to somehow be drawn to lights.

Insects that fly at night are attracted to artificial light all around the world. We are scientists who are curious about the effects of light pollution on moths and other insects, and that is what we investigate in our work. One of us grew up in Mexico. And one of us grew up in Alaska. When we were kids, we both remember insects flying and crashing against the street lights in front of our houses in different parts of the world. But now, it seems there are fewer and fewer insects flying around those same lights.

Why are moths and other insects important?

During the last several decades, the number of insects in forests, fields and cities seems to be declining. Insects are an important source of food for almost all other animals. They also do very important jobs like pollinating flowers or breaking down leaves and other organic matter to be used again by nature.

For years, scientists have tried to explain why moths and other insects are attracted to lights, but scientists are not entirely sure why!

We are currently designing experiments to determine which of several explanations might be true. One idea is that some insects use the Moon or bright stars as direction-finding aids. To moths, streetlights might look like the Moon, which could mislead them. Some insects spiral toward lights as if they are trying to keep the “Moon” off to the same side.

Another idea is that lights trick moths into seeing visual illusions of darker areas near the lights’ edges, called Mach bands, and moths fly toward these dark hiding places.

Yet another idea supposes that lights at night blind moths by swamping the light receptors in their eyes and disorienting them.

Could lights be partially to blame for fewer insects?

As scientists, we think that understanding how lights attract moths can help us understand why insects are declining. It may be that lights make insects easy prey by concentrating them in one place and interfering with their abilities to avoid bats. Or, when the Sun rises, insects may find themselves trapped on unnatural surfaces, where their camouflage doesn’t work: Now they are easy prey for birds and lizards.

Another problem could be that trapped insects, lured away from their normal habitat, are forced to lay their eggs far from the plants their young need to eat. And many insects likely die from exhaustion while circling lights.

If you would like to help insects, you can use yellow or red light bulbs on the outside of your house. These lights attract fewer insects. Motion sensor lights are helpful, too, because they turn on only when needed. As we explore how light pollution is affecting insects, our research can inform local and national governments on how to manage light to protect the natural world.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com. Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you’re wondering, too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.![]()

Carlos Linares, Ph.D. Candidate in Ecology, Evolution and Behavior and Biological Sciences, Boise State University and Jesse Barber, Associate Professor of Biological Sciences, Boise State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.