Curious Kids: Why is money green?

Jonah Estess, American University

Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to curiouskidsus@theconversation.com.

Why is money green? – Marek P., age 12, Dorchester, Massachusetts

We use money all the time, but have you ever wondered why it’s green?

As a student of the history of U.S. money, I study how people understand the purpose of money in their lives and how people feel about the way the government produces it.

Learning the history of money has helped me answer questions people have about why it comes in certain colors and not other colors. For example, why is U.S. money green, instead of orange, like it is in New Zealand?

Why green?

While our money is not completely green, it has lots of green ink on it. The green ink on paper money protects against counterfeiting. Counterfeiting is the process of making fake money that tricks people and the government into thinking that it is real money.

Counterfeiting is dangerous because it causes the value of the real money to go down. If this happens, people need more dollar bills, and therefore more money, to buy things. This special green ink is just one tool that the government uses to protect us from counterfeiters.

Also, there was lots of green ink for the government to use when it started printing the money we have now. The green color also does not fade or decompose easily.

When US money was different colors

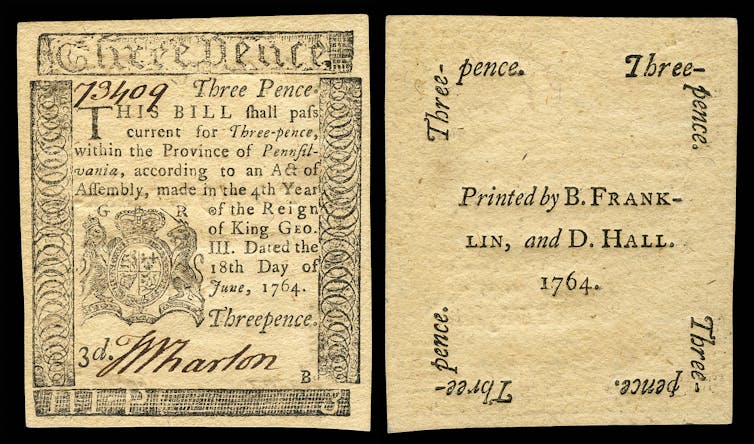

In Colonial America, the colonies printed their own currency for several reasons.

One reason was that colonists often did not have enough coins to buy food and household items. Colonial money was often intended to give colonists a way to buy what they needed or wanted. This money was initially tan with black or red ink.

During the American Revolution, the Continental Congress printed money that was also a tan color called continental dollars.

Just like the green color of our paper money today, the Continental Congress used a specific kind of material that only it could buy in order to prevent counterfeiting. The paper was made of cloth, sometimes silk and isinglass, which is somewhat see-through and made from fish air bladders.

After the revolution

The U.S. government didn’t print any paper money for a long time after the American Revolution, since Congress believed that Americans would trust coins more than paper money.

People no longer trusted paper money largely because too much counterfeit money existed during the Revolution. Besides, gold and silver coins were trustworthy because they were made of valuable metals.

Congress eventually passed a law called the Legal Tender Act of 1862 allowing the federal government to print paper money.

The government began printing money again because the government was struggling to pay for the Civil War. Both the Union and Confederacy printed their own money, and both sides used green ink partly because it made counterfeiting more difficult. Money printed by the Union came to be known as “greenbacks.”

Today, our money is green because the government has no real reason to change the color. The government is able to produce enough of it for people to use, can protect against counterfeiting and makes sure that we can trust our money to remain valuable.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to CuriousKidsUS@theconversation.com.

Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.![]()

Jonah Estess, Ph.D. Student of History, American University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.