Election polls in 2020 produced ‘error of unusual magnitude,’ expert panel finds, without pinpointing cause

© iStock - sefa ouzel

W. Joseph Campbell, American University School of Communication

More than eight months after the acute polling embarrassment in the 2020 U.S. elections – that produced the sharpest discrepancy between the polls and popular vote outcome since 1980 – survey experts examining what went wrong say they have no definitive answers about why polls erred as markedly as they did.

That inconclusive finding reported by a polling industry task force will do little to assuage popular skepticism about election polls which, in one way or another, have misfired in all U.S. presidential races but one since 1996.

And if the source of the 2020 polling error cannot be pinpointed, then addressing and correcting it obviously becomes daunting.

Moreover, as I discussed in my book “Lost in a Gallup,” polling failures in presidential elections since 1936 rarely have been repetitive. Just as no two elections are alike, no two polling failures are quite the same.

Over the years, pollsters have anticipated tight presidential elections when landslides have occurred. They have signaled the wrong winner in closer elections. The estimates of venerable pollsters have been singularly in error. Wayward exit polls have thrown Election Day into confusion by identifying the losing candidate as the likely winner. Off-target state polls have confounded expected national outcomes, which essentially was the story in 2016.

Trump support underestimated

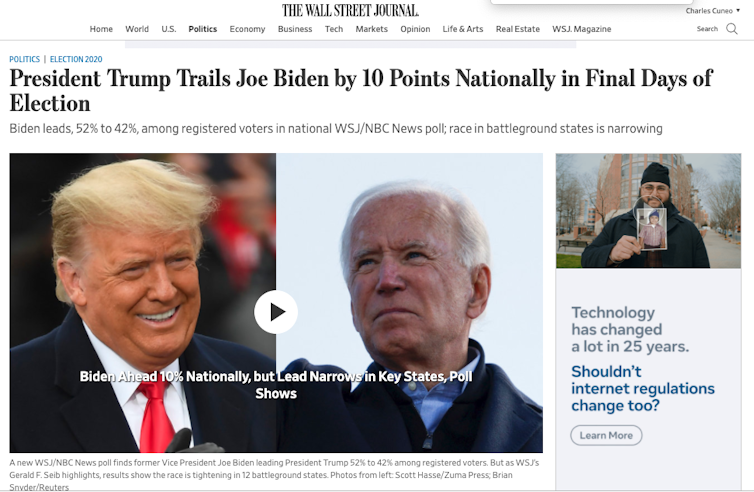

In 2020, election polls pointed to Democrat Joe Biden’s winning the presidency. But collectively, the polls underestimated backing for then-President Donald Trump no matter how close to the election the survey was conducted and regardless of the methods pollsters chose. Surveys in races for U.S. senator and governor were beset by similar flaws.

Those were among the findings described in a report made available on July 19, 2021, that noted that voter-preference surveys in 2020 “featured polling error of an unusual magnitude” and that the discrepancy in the presidential race was the greatest in 40 years.

The experts, who comprised a task force of the American Association for Public Opinion Research, a survey industry organization, speculated that some Republicans may have been less willing than Democrats to be interviewed by pollsters – a hypothesis that could explain some of the polling error. But the task force report said “identifying conclusively” why polls erred “appears to be impossible with the available data.”

The task force, which included 19 members from the polling industry, the news media and academia, said it reviewed data from more than 2,800 polls and found that surveys in the 2020 presidential race overstated Biden’s popular vote advantage by 3.9 percentage points.

This marked the fourth presidential election in the past five in which the national polls, at least to some extent, exaggerated support for Democratic candidates.

Masking dramatic miscalls

Averaging the polling errors, as the task force did in conducting its months-long analysis, is broadly revealing about the extent of those errors. But it also has the effect of masking several dramatic miscalls in late-campaign polls conducted in 2020 by, or for, leading news organizations.

The final CNN poll had Biden ahead by 12 points. Surveys for The Wall Street Journal-NBC News and by the Economist-YouGov had Biden winning by 10 percentage points as the campaign wound down. A few polls, such as Emerson College’s survey, came close in estimating the outcome.

Biden won the popular vote by 4.5 percentage points.

The report said the task force rejected several prospective causes of polling error in 2020 – including those that likely distorted survey results in key states in 2016 when Trump unexpectedly won an Electoral College victory. Those factors included undecided voters swinging to Trump late in the campaign and a failure by some pollsters to adjust survey results to account for varying levels of education.

White voters without college degrees were understood to have voted heavily for Trump in 2016, but those voters were underrepresented in some polls in key states such as Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, where Trump won narrowly and surprisingly.

The task force also rejected as a factor in 2020 any errors pollsters made in projecting the likely makeup of the electorate in terms of age, race, ethnicity and other factors – an estimate common to preelection surveys.

The task force reported finding “no evidence that polling error was caused by the underrepresentation or overrepresentation of particular demographics” in the preelection surveys.

Additionally, it is unclear whether Trump’s sharp criticism of preelection polls in 2020 dissuaded his supporters from participating in surveys.

“So it’s possible that these may be short-term phenomena that will abate when Trump is not on the ballot,” Daniel Merkle, the then-president of the American Association for Public Opinion Research, said in a speech in May.

[Over 106,000 readers rely on The Conversation’s newsletter to understand the world. Sign up today.]

“On the other hand,” Merkle said, “it could be a broader issue of conservatives becoming less likely to respond to polls in general because of a decline in social trust, or for some other reasons. It will take further evaluation to understand this nonresponse issue and to adjust for it.

"This may not be an easy task.”

Overblown characterizations

In the immediate aftermath of the 2020 election, several media critics declared that polling could be “irrevocably broken” and faced “serious existential questions.”

Such disquieting assertions seem overblown; polls are not going to melt away. After all, election polling represents a slice of a multibillion-dollar industry that includes consumer and product surveys of all types.

And if election polling survived the debacle of 1948 – when President Harry S. Truman defied predictions of pollsters and pundits to win reelection – then it surely will live on after the embarrassment of uncertain origin of 2020.

This is an updated version of an article originally published on May 20, 2021.![]()

W. Joseph Campbell, Professor of Communication Studies, American University School of Communication

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.