Evangelicals downplay religious expression when working with secular groups

Brad R. Fulton, Indiana University

White evangelicals in the United States are typically presented as culture warriors united around a common set of conservative aims, such as preserving “traditional family values” and in opposition to secular groups.

Evangelicals make up roughly one-quarter of the U.S. population. This percentage has remained steady over the past two decades, despite the persistent decline in the percentage of Americans who identify as religious, which has dropped from 86% to 77%.

Evangelicals are known for emphasizing the country’s “Christian heritage,” promoting forms of ethno-religious nationalism and pursuing legislative agendas such as providing staunch support for Israel.

Despite being portrayed as hyper-religious and persistent proselytizers, my research indicates that some evangelicals actually downplay religious expression when working with religiously diverse and secular groups.

Studying evangelicals

As a scholar of religion and politics, I wanted to learn more about how white evangelicals engage with religious diversity and an increasingly nonreligious U.S. society. So I teamed up with sociologists Wes Markofski and Richard L. Wood to conduct in-depth field research with multifaith initiatives in Boston, Atlanta, Los Angeles and Portland, Oregon.

Our study focused primarily on white evangelicals living in urban and suburban settings, where the majority of white evangelicals live. Cities are also where the largest, fastest-growing and most influential evangelical churches are located.

A secular way of acting

We studied evangelicals within a variety of multifaith collaborations, including policy advocacy organizations and volunteer initiatives like Serving the City in Portland.

As we explain in the journal Sociology of Religion, we found that in such religiously diverse and secular contexts, evangelicals tend to downplay religious expression.

For example, we found that when the 26,000 evangelicals from 500 churches volunteered with Portland’s Serving the City initiative, they adopted a self-imposed “no-proselytizing” policy as they helped with cleaning up parks, refurbishing schools and conducting clothing drives.

One suspicious school principal with strong views on church–state separation eventually became supportive of the evangelicals’ involvement. He noted that “they are not in the hallways passing out tracts, they’re not proselytizing, but they’re simply asking, ‘What do you need? And how can we help?’”

These evangelicals said they want to simply serve their neighbors. As one evangelical leader put it, “The reason this works … is that we’ve agreed to play by the rules: serving with no strings attached.”

We observed evangelicals adopting a similar approach in various parts of the U.S., including places considered more progressive and secular like New England and the West Coast as well as the South, where Christianity plays a more prominent cultural role.

Furthermore, the findings from our fieldwork extend to politically centrist and conservative evangelical organizations – not just a politically liberal subset of evangelicals, from whom a secular approach might be more expected.

A broader pattern

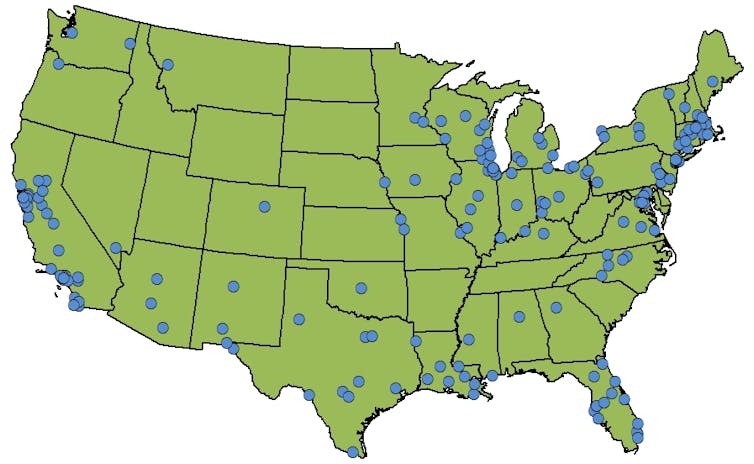

To assess whether these findings point to a broader trend, we analyzed data from the National Study of Community Organizing. I led this study, which collected information on 3,225 religious congregations involved in 178 community organizing efforts spread throughout the U.S.

Findings from this study indicate that white evangelicals are more likely to participate in coalitions that display minimal religious expression. For example, our analysis finds that among the participating white evangelical congregations, they are twice as likely to join a coalition that does not open or close its meetings with prayer.

We had not expected to find this preference, given how much evangelicals emphasize prayer.

This finding is consistent with a multifaith coalition we observed in Los Angeles that addressed issues regarding underemployment, immigrant rights and environmental justice, among others. When that group met, it did not begin its meetings with a prayer or spiritual reflection, nor did it frame its social justice goals in religious terms.

Other research cites a growing number of evangelicals approaching public engagement in a similar way. For example, the edited volume “The New Evangelical Social Engagement,” compiled by scholars Brian Steensland and Philip Goff, provides several examples of evangelicals working with secular groups to address politically progressive issues.

Similarly, scholar Marcia Pally describes in her book “America’s New Evangelicals” a movement of evangelicals collaborating across religious-secular divides to advance the common good.

American evangelicals, in other words, are not monolithic. Their priorities and approach to public life and politics vary substantially.

Avoiding stigma or building bridges?

Scholars point to several reasons why some white evangelicals are inclined to temper religious expression in certain contexts, even as faith remains central to their identity and politics.

Religion scholar Peter Schuurman explains that some do so to avoid stigma. In many urban settings, evangelicals represent the intolerant “other” against which many progressive social movements position themselves. Downplaying religious expression could help them gain trust and reshape public perceptions.

Researcher Heidi Unruh believes evangelicals are just being pragmatic when they downplay their faith in mixed settings. Avoiding areas of disagreement allows them to pursue shared goals without compromising their religious beliefs.

While their reasons might be varied, as the U.S. becomes increasingly secular but also divided along religious lines, it is noteworthy the approach some white evangelicals are taking to bridge these divides.

[You’re smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation’s authors and editors. You can read us daily by subscribing to our newsletter.]![]()

Brad R. Fulton, Assistant Professor, O’Neill School of Public and Environmental Affairs, Indiana University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.