How the FBI knew what to search for at Mar-a-Lago

Shannon Bow O'Brien, The University of Texas at Austin College of Liberal Arts

The FBI search of former President Donald Trump’s Florida estate, Mar-a-Lago, on Aug. 8, 2022, has sparked a vigorous outcry from Trump and his allies. The details of the search are not clear, but reporting by The New York Times confirms that the search was “at least in part” for presidential records that Trump had taken from the White House and which were being sought by the National Archives and Records Administration. We asked Shannon Bow O'Brien, a scholar of the presidency at the University of Texas, Austin College of Liberal Arts, to discuss the history, law and customs associated with presidential archives.

How do the archivists actually know what’s missing? Isn’t that hard to figure out?

The archivists probably have a really keen idea of what is and what isn’t missing, based upon things that they’ve gotten out of other offices, like the vice president’s office and things that got deposited from the secretary of state, for example. There are a lot of papers that are referenced and cross-referenced, multiple copies or multiple things going in and out of offices.

One scholar did a study of the presidents’ annual Christmas speech at the Ellipse in Washington. He looked at how the speeches – from the Roosevelt administration to the present – developed, and it was kind of a ring-around-the-rosy inside the West Wing and within the departments – what went in, what went out, what went in, what went out. Who won and who didn’t win. Everybody left their marks on the speeches. All of those changes and requests appear in documents, and if part of the conversation is missing from the National Archives, it’s obvious.

We know from other presidents’ records that really comprehensive records are kept via daily manifests of what the presidents are doing. And while I am not a historian, it’s not unreasonable to assume that the other departments and agencies likewise have daily manifests of their top officials. So if they know that someone at an agency sent something over to the White House that was this or that, and it came back from the White House with this or that, then there should be a document somewhere that’s got something from the White House on it – and if you’re missing that, that’s a problem.

Will the public find out what was in these documents, given that they are classified?

We’ll be lucky to know if, and when, the documents get declassified. We might get some hints of what is there if Trump does get indicted for a crime related to removing the documents or based on something found in them. We’ll possibly find out what grade of classification the documents had – they get different levels based on the level of seriousness.

What’s the law that governs what happens to a president’s documents?

It’s the Presidential Records Act. It came about originally because these guys, the presidents, were just kind of doing whatever the heck they wanted with their records. Hoover donates his; FDR doesn’t.

The act, first passed in 1978, says administrations have to retain “any documentary materials relating to the political activities of the President or members of the President’s staff, but only if such activities relate to or have a direct effect upon the carrying out of constitutional, statutory, or other official or ceremonial duties of the President.”

An administration is allowed to exclude personal records that are purely private or don’t have an effect on the duties of a president. All public events are included, such as quick comments on the South Lawn, short exchanges with reporters and all public speeches, radio addresses and even public telephone calls to astronauts in space. Diaries and journals are off limits, but any papers to carry out the job are public records.

Have there been other controversies over presidential records?

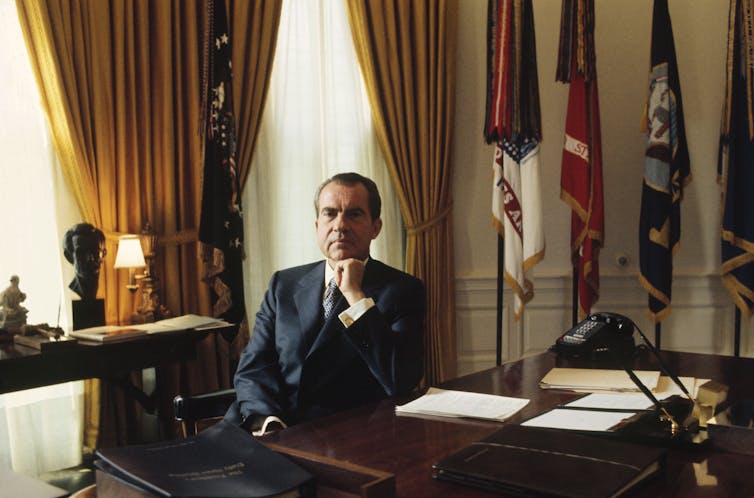

There’s one that poses an essential question: What value can you place on history? In 1998, the Nixon estate felt his records had a monetary value of over US$200 million and sued the government, which had seized the records, for what they believed their value amounted to.

There’s a two-decade background to the case. After he left the presidency, Nixon brokered a deal with the General Services Administration about the retention of his records, but when knowledge of it became public, there was considerable outcry. A large amount of material was to be withheld from public view, and there was concern the depth of Nixon’s true involvement in Watergate would be obscured.

Congress responded and in 1974, President Gerald Ford signed the Presidential Recordings and Materials Preservation Act to specifically apply to Nixon’s presidential materials. It gave the archivists the power to seize materials from Nixon’s time in the White House and return those deemed private.

Nixon immediately sued over who possessed his records. While he had already been pardoned when it was enacted, Nixon was concerned about his reputation and legacy. He wanted control over what the public saw about his time in office. One of the major issues in front of the court involved the disposition of documents he believed were private. Given the scandal associated with his resignation, should these documents be inspected by archivists for veracity?

More important, did the government have the right to seize presidential documents?

In a 7-2 decision, the Supreme Court rejected all of Nixon’s arguments. They said his privacy rights were still intact because the archivists were not making things immediately public but inspecting them and retaining public items while returning family ones. The court noted the “unblemished record of the archivists for discretion.”

In 2000, the lawsuit was settled over the Nixon records, with the bulk of the settlement money going to pay attorney fees. Some observers were unhappy, because these documents should have already been considered public, but the decision was likely made to finally close this chapter on American history. In 2007, the Nixon library in California became public and integrated into National Archives.

This story includes parts of an article originally published on Feb. 11, 2022.![]()

Shannon Bow O'Brien, Associate Professor of Instruction, The University of Texas at Austin College of Liberal Arts

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.