Humans are 8% virus – how the ancient viral DNA in your genome plays a role in human disease and development

Humans are 8% virus – how the ancient viral DNA in your genome plays a role in human disease and development

Remnants of ancient viral pandemics in the form of viral DNA sequences embedded in our genomes are still active in healthy people, according to new research my colleagues and I recently published.

HERVs, or human endogenous retroviruses, make up around 8% of the human genome, left behind as a result of infections that humanity’s primate ancestors suffered millions of years ago. They became part of the human genome due to how they replicate.

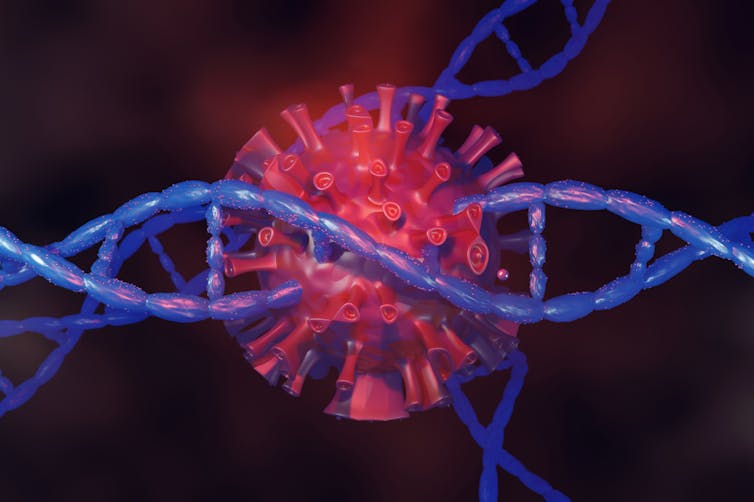

Like modern HIV, these ancient retroviruses had to insert their genetic material into their host’s genome to replicate. Usually this kind of viral genetic material isn’t passed down from generation to generation. But some ancient retroviruses gained the ability to infect germ cells, such as egg or sperm, that do pass their DNA down to future generations. By targeting germ cells, these retroviruses became incorporated into human ancestral genomes over the course of millions of years and may have implications for how researchers screen and test for diseases today.

Active viral genes in the human genome

Viruses insert their genomes into their hosts in the form of a provirus. There are around 30 different kinds of human endogenous retroviruses in people today, amounting to over 60,000 proviruses in the human genome. They demonstrate the long history of the many pandemics humanity has been subjected to over the course of evolution. Scientists think these viruses once widely infected the population, since they have become fixed in not only the human genome but also in chimpanzee, gorilla and other primate genomes.

Research from our lab and others has demonstrated that HERV genes are active in diseased tissue, such as tumors, as well as during human embryonic development. But how active HERV genes are in healthy tissue was still largely unknown.

To answer this question, our lab decided to focus on one group of HERVs known as HML-2. This group is the most recently active of the HERVs, having gone extinct less than 5 million years ago. Even now, some of its proviruses within the human genome still retain the ability to make viral proteins.

We examined the genetic material in a database containing over 14,000 donated tissue samples from all across the body. We looked for sequences that matched each HML-2 provirus in the genome and found 37 different HML-2 proviruses that were still active. All 54 tissue samples we analyzed had some evidence of activity of one or more of these proviruses. Furthermore, each tissue sample also contained genetic material from at least one provirus that could still produce viral proteins.

The role of HERVs in human health and disease

The fact that thousands of pieces of ancient viruses still exist in the human genome and can even create protein has drawn a considerable amount of attention from researchers, particularly since related viruses still active today can cause breast cancer and AIDS-like disease in animals.

Whether the genetic remnants of human endogenous retroviruses can cause disease in people is still under study. Researchers have spotted viruslike particles from HML-2 in cancer cells, and the presence of HERV genetic material in diseased tissue has been associated with conditions such as Lou Gehrig’s disease, or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, as well as multiple sclerosis and even schizophrenia.

Our study adds a new angle to this data by showing that HERV genes are present even in healthy tissue. This means that the presence of HERV RNA may not be enough to connect the virus to a disease.

Importantly, it also means that HERV genes or proteins may no longer be good targets for drugs. HERVs have been explored as a target for a number of potential drugs, including antiretroviral medication, antibodies for breast cancer and T-cell therapies for melanoma. Treatments using HERV genes as a cancer biomarker will also need to take into account their activity in healthy tissue.

On the other hand, our research also suggests that HERVs could even be beneficial to people. The most famous HERV embedded in human and animal genomes, syncytin, is a gene derived from an ancient retrovirus that plays an important role in the formation of the placenta. Pregnancy in all mammals is dependent on the virus-derived protein coded in this gene.

Similarly, mice, cats and sheep also found a way to use endogenous retroviruses to protect themselves against the original ancient virus that created them. While these embedded viral genes are unable to use their host’s machinery to create a full virus, enough of their damaged pieces circulate in the body to interfere with the replication cycle of their ancestral virus if the host encounters it. Scientists theorize that one HERV may have played this protective role in people millions of years ago. Our study highlights a few more HERVs that could have been claimed or co-opted by the human body much more recently for this same purpose.

Unknowns remain

Our research reveals a level of HERV activity in the human body that was previously unknown, raising as many questions as it answered.

There is still much to learn about the ancient viruses that linger in the human genome, including whether their presence is beneficial and what mechanism drives their activity. Seeing if any of these genes are actually made into proteins will also be important.

Answering these questions could reveal previously unknown functions for these ancient viral genes and better help researchers understand how the human body reacts to evolution alongside these vestiges of ancient pandemics.![]()

Aidan Burn, PhD Candidate in Genetics, Tufts University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.