Native American tribes' pandemic response is hamstrung by many inequities

Lindsey Schneider, Colorado State University; Joshua Sbicca, Colorado State University, and Stephanie Malin, Colorado State University

The SARS-CoV-2 virus is novel, but pandemic threats to indigenous peoples are anything but new. Diseases like measles, smallpox and the Spanish flu have decimated Native American communities ever since the arrival of the first European colonizers.

Now COVID-19 is having similarly devastating impacts in Indian country. Some reservations are reporting infection rates many times higher than those observed in the general U.S. population.

We are social scientists who study many aspects of environmental justice, including the politics of food access and food sovereignty, the impacts of extractive resource industries like uranium and fossil fuels, and how Indigenous communities navigate relationships with state and federal governments to maintain their traditional practices. As we see it, Native American communities face structural and historical obstacles related to settler colonial legacies that make it hard for them to counter the pandemic, even by drawing on innovative indigenous survival strategies.

History reverberates on Native lands

Native communities in North America have been disrupted and displaced for centuries. Many face long-standing food and water inequities that are further complicated by this pandemic.

On the Navajo reservation, which covers more than 27,000 square miles in Arizona, Utah and New Mexico, 76% of households already have trouble affording enough healthy food, and the nearest grocery store is often hours away. COVID-related restrictions have further curtailed access to food supplies.

Clean water for basic sanitary measures like hand-washing is also scarce. Native Americans are 19 times more likely to lack indoor plumbing than whites in the U.S. Nearly one-third of Navajo households lack access to running water.

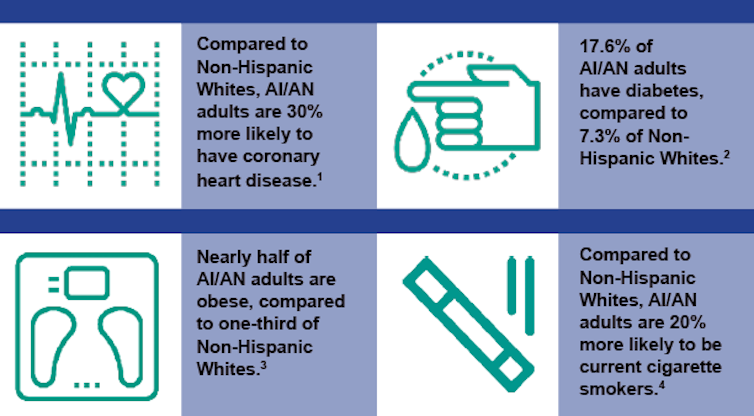

Many health issues that can increase COVID-19 mortality rates occur at high levels among Native Americans. These underlying and preexisting conditions – things like hypertension, diabetes, obesity and cardiovascular disease – are linked to diet and stem from disruption and replacement of Indigenous food systems.

Meanwhile, housing shortages on reservations and homelessness in urban Native communities make social distancing to reduce COVID-19 transmission impossible.

High exposure rates

These factors have clear health impacts. On the Navajo reservation, for instance, through May 27, 2020, 4,944 people out of a population of 173,000 had tested positive for COVID-19, and 159 had died.

This infection rate per capita exceeds those in hot spots such as New York and New Jersey. Importantly, however, it may also reflect a much more proactive approach to testing on reservations than in many other jurisdictions.

The fact that elderly people are especially vulnerable to COVID-19 could worsen the pandemic’s effects in Indian Country. Elders are the keepers of traditional knowledge, tribal languages and culture – legacies whose loss already threatens the persistence of indigenous communities.

Elders also play key roles in preserving traditional plant and medicine knowledge. In the absence of COVID-19 interventions from Western medicine, many elders have been called on to perform healing practices, which increases their exposure risk.

Little help from federal and state governments

Many tribal members rely on the federal government’s Indian Health Service for health care. But lack of capacity at the agency has hampered its response. Budget shortfalls, inaccurate data, the challenges of providing rural health care and ongoing personnel shortages in IHS clinics are compounded by staff being pulled away to fight the virus in large cities.

And while many states have raised frustrations with the Trump administration’s unwillingness to distribute protective supplies from the dwindling national stockpile, IHS and tribal health care authorities never had access to the stockpile at all.

Although the federal government has begun distributing relief funds to IHS agencies, there have been serious problems with the accompanying supplies. The Navajo Nation has received faulty masks, and a Seattle Native health center asked for tests but received body bags instead.

Meanwhile, federally imposed limits on tribal sovereignty have obstructed tribal governments’ efforts to deal with the pandemic themselves. Federal and state governments are challenging tribes’ jurisdictional authority to close borders to tourists who may carry the virus. South Dakota’s governor has threatened legal action against two tribes who set up checkpoints to monitor incoming traffic on their reservations.

Environmental injustices on Native land

Energy development and resource extraction have had disproportionate impacts on tribes for many years. Today, many Native American leaders worry that ongoing energy production – an “essential” activity under federal guidelines will bring outsiders into close contact with reservation communities, worsening COVID risks.

The owners of the Keystone XL oil pipeline have announced that they intend to continue construction, which will bring an influx of workers along the proposed route through Montana, South Dakota and Nebraska. The Rosebud Sioux Tribe in South Dakota and Fort Belknap Indian community in Montana have filed for a temporary restraining order, and a key permit for the pipeline was revoked in April 2020, but work continues at the U.S.-Canada border.

Construction is accelerating on the southern border wall, which bisects the Tohono O’odham reservation in Arizona and Mexico. The Trump administration has increased patrols at the border, despite the tribe’s concern that the patrols’ presence is spreading coronavirus on the reservation.

And in Bristol Bay, Alaska, a salmon fishing season that brings in thousands of temporary workers is set to open in June because the federal government has also deemed commercial fishing “essential critical infrastructure.” Many local Native villages depend on the fishery for income, but have nonetheless pleaded with state regulators to cancel the season. The regional hospital has just four beds for possible COVID-19 patients.

Bold action in Native communities

Native communities are taking decisive action to reduce the spread of COVID-19. They’re imposing aggressive quarantine measures like lockdowns, curfews and border closures. Communities are ramping up health care capacity and elder support services, and banishing nontribal members who violate travel restrictions.

Other strategies include helping hunters provide traditional foods to their communities, mobilizing to support tribal health care workers, and linking the pandemic and the climate crisis. Looking ahead to a post-COVID future, we believe one priority should be attending to front-line environmental justice struggles that center tribes’ sovereignty to act on their own behalf at all times, not just during national crises.

[Get facts about coronavirus and the latest research. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]![]()

Lindsey Schneider, Assistant Professor of Native American Studies, Colorado State University; Joshua Sbicca, Associate Professor of Sociology, Colorado State University, and Stephanie Malin, Associate Professor of Sociology; Co-Founder and Steering Committee Member, Center for Environmental Justice at CSU, Colorado State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.