The new Congress and the history of governing by a house divided

Brooks D. Simpson, Arizona State University

As the 116th Congress convenes this week, power has shifted from Republican control of both the Senate and House to a Republican Senate and a Democratic House, poised to battle each other under a Republican president who is under fire.

How can American political history help us anticipate what might be in the offing?

Congressional division means conflict

The Democratic takeover of the House was not unusual. The party not in power in the White House usually gains ground during midterm elections. That’s especially true in the House of Representatives, where all seats are up for grabs every two years.

Four previous midterm elections that produced divided Congresses suggest what to expect over the next two years.

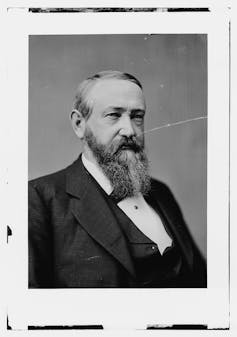

In 1890 and 1910 Democratic majorities in the House brought an end to the agendas of presidents Benjamin Harrison and William Howard Taft, both Republicans, and set the stage for Democratic triumphs in the presidential contests of 1892 and 1912.

Harrison had promoted tariffs and federal protection for black voters, but neither policy stood a chance of legislative success given the Democrats’ House majority.

Perhaps the most noteworthy achievement of Congress during Taft’s final two years was the framing of a constitutional amendment providing for the direct popular election of United States senators. Previously, state legislatures had usually that selection. Proposed constitutional amendments are not subject to presidential veto, so the process bypassed Taft altogether. The amendment was ratified in April 1913.

Lots of questions ahead

Two other historic midterm setbacks for the party in power support a forecast for more combative politics during the next two years. They suggest that a Democratic-controlled House of Representatives can undertake investigations of the Republican administration that could bring a presidency to a halt.

In the fall of 1858, Republicans secured control of the House of Representatives. They quickly went to work to investigate the wrongdoings of James Buchanan’s already stumbling presidency.

The investigation scrutinized allegations that Buchanan and members of his administration had bribed Democrats with either money or patronage jobs. Those bribes were to ensure the success of administration policies to admit Kansas to the union as a slave state and to reward Democratic supporters with government contracts.

The committee didn’t gather sufficient evidence to secure Buchanan’s impeachment. But it uncovered enough wrongdoing to damage his presidency as well as the Democratic Party in a presidential election year – the 1860 election that resulted in Republican Abraham Lincoln’s victory.

Sixteen years later, the Democrats got their revenge when they regained control of the House in the midterm elections of 1874.

Their electoral victory, Democrats believed, hinged on a combination of unfortunate elements that hurt Republicans.

Those elements included the onset of an economic depression in 1873, revelations of corrupt behavior among leading congressional Republicans, and the growing unpopularity of Reconstruction. Southern Democrats also benefited from efforts to suppress black political participation through violence and intimidation.

The Democratic triumph proved the death knell for Republican efforts to promote Reconstruction through federal legislation, especially to secure the protection of black rights.

Vigorously using the power to launch investigations, Democrats struck telling blows against Ulysses S. Grant’s administration.

They exposed the corrupt behavior of several cabinet members, notably Secretary of War William Belknap, who was charged with accepting kickbacks from holders of frontier trading posts. The House impeached Belknap, who escaped conviction only because he had already resigned.

Other House investigations also damaged the reputations of Grant’s brother Orvil, who was also involved in accepting kickbacks for trading post licenses, and Secretary of the Navy George M. Robeson, who was accused of improper dealing with shipbuilding contracts.

Adding to Grant’s woes was the fact that his own secretary of the treasury had been pursuing the prosecution of the president’s private secretary for revenue fraud. Grant retired from office with a reputation for presiding over a cesspool of corruption rarely seen in our nation’s history.

Both parties ran reform candidates in 1876, with the victorious Rutherford B. Hayes, a Republican, pledging to end federal support for black voting rights in the South.

Stalemate and struggle

Even if the majority party retains control of both the presidency and both houses of Congress, a president may still find his agenda languishes. Franklin D. Roosevelt’s desire for additional New Deal initiatives was frustrated by Republican gains in 1938. Those gains allowed the minority party to join with southern Democrats to block further legislation.

Sometimes the opposition party increases its control of both houses. In 1866, an overwhelming Republican triumph led to veto-proof majorities in the Senate and the House.

Just two years after the end of slavery, Republicans wanted to pass Reconstruction legislation to re-establish state governments throughout the South that included African-Americans as voters, convention delegates and officeholders.

When Democratic President Andrew Johnson tried to obstruct the legislation’s passage, lawmakers overrode his vetoes.

On occasion, the party in the White House loses control of both houses of Congress, forcing the president to seek common ground with his political foes where possible. Just as often, the outcome results in stalemate and confrontation.

President Bill Clinton resisted House Speaker New Gingrich’s vision of a “Contract with America,” which promoted slashing various federal programs, eventually leading to a pair of government shutdowns totalling 27 days in 1995 and 1996.

President Barack Obama found it difficult to get anything done after the 2010 midterms brought to Congress a Republican majority determined to block administration initiatives.

Enough power to investigate, not legislate

While today’s House Democrats hold different political beliefs than did their party brethren 144 years ago, they confront a similar situation.

A Republican president and Senate spell doom for the Democratic House’s legislative agenda. But Democrats can check their foes’ ambitions.

A target-rich environment of rumored corruption, malfeasance and scandal may prove sufficiently tempting to spark a series of investigations that could undermine the Trump presidency. They could also enhance Democratic political prospects for 2020.![]()

Brooks D. Simpson, Faculty Head and Professor of Interdisciplinary Humanities and Communication, Arizona State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.