Presidential hopefuls are considering these 5 practical factors before launching their 2024 campaigns

Robbin Mellen Jr., University of South Florida

The 2024 race for the White House is in motion. Democratic incumbent President Joe Biden said in October 2022 that he intends to seek a second term, even if he stopped short of making an official announcement. But – in what is expected to be a crowded Republican field – only a few candidates had announced their bids by late March 2023.

Former President Donald Trump, the last Republican to hold the office and party standard-bearer, said in November 2022 that he will seek the party’s nomination. And Republican Nikki Haley, one-time U.S. ambassador to the United Nations and former governor of South Carolina, announced in February 2023 that she is running.

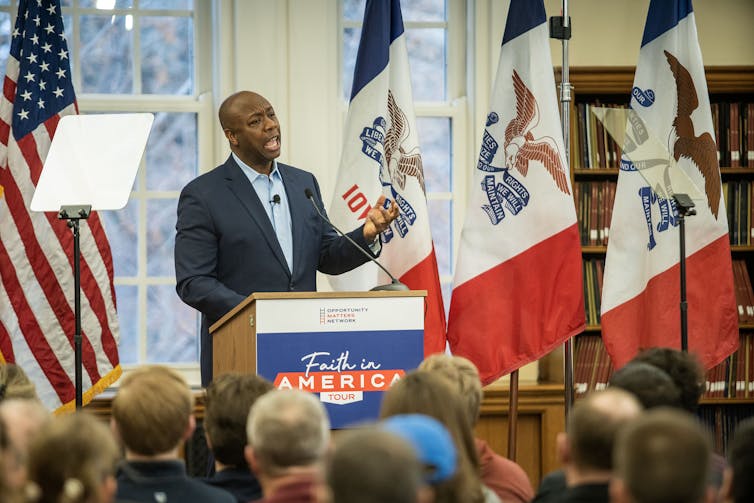

In the weeks and months ahead, more presidential hopefuls likely will enter the race. Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, for example, is expected to jump in after his state’s legislative session ends in May. And Sen. Tim Scott, of South Carolina, appears ready to announce soon.

Each candidate, along with their campaigns, makes decisions about the right time to jump into the race. But how do they decide?

The Conversation asked Rob Mellen Jr., a political scientist who studies the presidency, to explain five things presidential hopefuls consider before running for the highest office in the land.

1. Incumbent eligibility

The first thing potential presidential candidates consider is whether the incumbent president or, for the party out of office, the standard-bearer, is eligible to seek office.

Candidates who oppose incumbents - and popular past presidents of the same party - face nearly insurmountable obstacles, largely due to incumbent popularity. It offers officeholders seeking reelection a significant advantage. Between 1952 and 2000, for example, incumbent presidents enjoyed a 6 percentage point bonus in the popular vote.

Typically, incumbents have advantages because of their track records, name recognition – which affects a candidate’s level of voter and financial support – and their ability to direct federal money to the geographic areas that support them.

While the incumbent’s advantages typically cause potential challengers to think twice before running for president, there have been exceptions. In 1980, Sen. Ted Kennedy of Massachusetts unsuccessfully challenged incumbent President Jimmy Carter for the Democratic nomination. Kennedy failed, though, and his bid divided the Democratic Party.

Republican Ronald Reagan, a former governor of California, beat Carter in the general election and became the nation’s 40th president.

2. The number of possible opponents

Potential candidates also consider the number of opponents they will have to compete against. A crowded field with numerous candidates makes it difficult for more than a three or four to gain traction before the first primary contests, which are usually held in January and February of election year.

If they are not the incumbent, a party standard-bearer or someone with otherwise significant name recognition, candidates with a lot of opponents typically find it tough to get their messages across, especially if they are competing against political stars.

During the 2016 Republican campaign, for example, 17 candidates entered the race, but only Trump and Sen. Ted Cruz stood out. Because of Trump’s celebrity status – earned from years of marketing himself as a billionaire and through reality television fame – Trump got a lot of attention from the media. His bombastic personality also played well with a segment of the Republican base. He drew significant media attention that other candidates could not match. And Cruz gained traction by finishing first in the Iowa caucuses, which allowed him to be competitive in the New Hampshire and South Carolina primaries that followed.

3. Likely voters

Candidates have a few ways to identify their likely voters. They can visit early contest states and test their messages, just like Trump, DeSantis, Haley and Scott have been doing in Iowa and South Carolina. Or, they can deliver speeches at major gatherings of party loyalists, such as the annual Conservative Political Action Conference.

Conducting polls is another way for candidates to figure out how broad, or narrow, their bases of support are.

4. Campaign Finance

Most presidential candidates also have to figure out how to finance what could become a lengthy bid for the party nomination. The main question they have to answer for themselves is, where will the money come from for sustained primary battles?

Connecting with wealthy backers who can can contribute large sums to a super PAC that supports the candidate can be the key to a candidate’s staying power.

Sometimes, committed large donors enable candidates to stay in the race much longer than expected, just as having backing from wealthy supporters and a super PAC prolonged former House Speaker Newt Gingrich’s failed presidential bid in 2012.

But, as Gingrich’s run proved, having the backing of a super PAC, which is legally prohibited from coordinating efforts with candidates and their campaigns, is not a guarantee of success.

Former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush’s 2016 campaign had the backing of the super PAC Right to Rise with a budget of over US$100 million. But his run for president ended after a disappointing fourth-place finish in the South Carolina primary.

Whether or not potential candidates have access to significant financial support influences their decisions to enter the race. It is extremely expensive to run a competitive campaign because of costs associated with staffing, travel, advertising and more. But candidates who fare well in the early contests tend to raise more money and survive longer in the primary process.

5. The mood of the electorate

The mood of the electorate also influences potential candidates’ decisions about whether to run. If the incumbent president is very popular – a rarity in modern American politics – it may scare off some would-be challengers.

But the public can be fickle. An incumbent may be popular a year before the general election, just as George H.W. Bush was in early 1991, only to see their popularity fade the following year. Bush lost the election to Bill Clinton in 1992.

The political fortunes of unpopular incumbents also can shift. In 1983, Reagan’s favorability ratings were very weak, but he rebounded by 1984 and beat Democratic candidate and former Vice President Walter Mondale in a 49-state landslide victory.

During presidential election years when there is no incumbent, as in 2008 and 2016, potential candidates’ calculations don’t have to include incumbent popularity. In 2016, both Trump and Sen. Bernie Sanders, an independent from Vermont who sought the Democratic nomination, were able to tap into an electorate looking for change by appealing to supporters with populist messages.

Trump’s effort successfully secured the Republican nomination, while Sanders’ effort came up short as the Democratic party favored its first female nominee, former Sen. Hillary Clinton.

From determining whether an incumbent president is vulnerable to a challenge from within the party to the likelihood of defeating an incumbent of the opposite party, a significant amount of strategic planning is involved in any effort to win the presidency. And the planning begins long before the day candidates announce their intention to run.![]()

Robbin Mellen Jr., Assistant Professor of Political Science, University of South Florida

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.