'Renewable' natural gas may sound green, but it's not an antidote for climate change

Natural gas is a versatile fossil fuel that accounts for about a third of U.S. energy use. Although it produces fewer greenhouse gas emissions and other pollutants than coal or oil, natural gas is a major contributor to climate change, an urgent global problem. Reducing emissions from the natural gas system is especially challenging because natural gas is used roughly equally for electricity, heating, and industrial applications.

There’s an emerging argument that maybe there could be a direct substitute for fossil natural gas in the form of renewable natural gas (RNG) – a renewable fuel designed to be nearly indistinguishable from fossil natural gas. RNG could be made from biomass or from captured carbon dioxide and electricity.

Based on what’s known about these systems, however, I believe climate benefits might not be as large as advocates claim. This matters because RNG isn’t widely used yet, and decisions about whether to invest in it are being made now, in places like California, Oregon, Washington, Michigan, Georgia and New York.

As someone who studies sustainability, I research how decisions made now might influence the environment and society in the future. I’m particularly interested in how energy systems contribute to climate change.

Right now, energy is responsible for most of the pollution worldwide that causes climate change. Since energy infrastructure, like power plants and pipelines, lasts a long time, it’s important to consider the climate change emissions that society is committing to with new investments in these systems. At the moment, renewable natural gas is more a proposal than reality, which makes this a great time to ask: What would investing in RNG mean for climate change?

What RNG is and why it matters

Most equipment that uses energy can only use a single kind of fuel, but the fuel might come from different resources. For example, you can’t charge your computer with gasoline, but it can run on electricity generated from coal, natural gas or solar power.

Natural gas is almost pure methane, currently sourced from raw, fossil natural gas produced from deposits deep underground. But methane could come from renewable resources, too.

[The Conversation’s science, health and technology editors pick their favorite stories. Weekly on Wednesdays.]

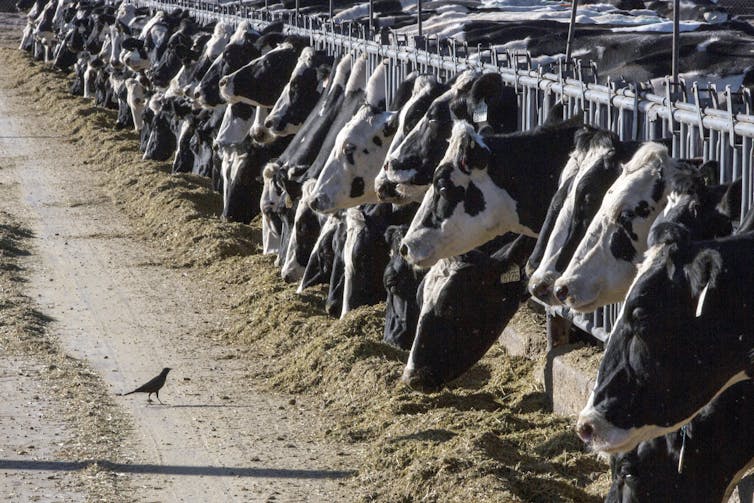

Two main methane sources could be used to make RNG. First is biogenic methane, produced by bacteria that digest organic materials in manure, landfills and wastewater. Wastewater treatment plants, landfills and dairy farms have captured and used biogenic methane as an energy resource for decades, in a form usually called biogas.

Some biogenic methane is generated naturally when organic materials break down without oxygen. Burning it for energy can be beneficial for the climate if doing so prevents methane from escaping to the atmosphere.

In theory, there’s enough of this climate-friendly methane available to replace about 1% of the energy that the current natural gas system provides. The largest share is found at landfills.

The other source for RNG doesn’t exist in practice yet, but could theoretically be a much larger resource than biogenic methane. Often called power-to-gas, this methane would be intentionally manufactured from carbon dioxide and hydrogen using electricity. If all the inputs are climate-neutral – meaning, for example, that the electricity used to create the RNG is generated from resources without greenhouse gas emissions – then the combusted RNG would also be climate-neutral.

So far, RNG of either type isn’t widely available. Much of the current conversation focuses on whether and how to make it available. For example, SoCalGas in California, CenterPoint Energy in Minnesota and Vermont Gas Systems in Vermont either offer or have proposed offering RNG to consumers, in the same way that many utilities allow customers to opt in to renewable electricity.

Renewable isn’t always sustainable

If RNG could be a renewable replacement for fossil natural gas, why not move ahead? Consumers have shown that they are willing to buy renewable electricity, so we might expect similar enthusiasm for RNG.

The key issue is that methane isn’t just a fuel – it’s also a potent greenhouse gas that contributes to climate change. Any methane that is manufactured intentionally, whether from biogenic or other sources, will contribute to climate change if it enters the atmosphere.

And releases will happen, from newly built production systems and existing, leaky transportation and user infrastructure. For example, the moment you smell gas before the pilot light on a stove lights the ring? That’s methane leakage, and it contributes to climate change.

To be clear, RNG is almost certainly better for the climate than fossil natural gas because byproducts of burning RNG won’t contribute to climate change. But doing somewhat better than existing systems is no longer enough to respond to the urgency of climate change. The world’s primary international body on climate change suggests we need to decarbonize by 2030 to mitigate the worst effects of climate change.

Scant climate benefits

My recent research suggests that for a system large enough to displace a lot of fossil natural gas, RNG is probably not as good for the climate as is publicly claimed. Although RNG has lower climate impact than its fossil counterpart, likely high demand and methane leakage mean that it probably will contribute to climate change. In contrast, renewable sources such as wind and solar energy do not emit climate pollution directly.

What’s more, creating a large RNG system would require building mostly new production infrastructure, since RNG comes from different sources than fossil natural gas. Such investments are both long-term commitments and opportunity costs. They would devote money, political will and infrastructure investments to RNG instead of alternatives that could achieve a zero greenhouse gas emission goal.

When climate change first broke into the political conversation in the late 1980s, investing in long-lived systems with low but non-zero greenhouse gas emissions was still compatible with aggressive climate goals. Now, zero greenhouse gas emissions is the target, and my research suggests that large deployments of RNG likely won’t meet that goal.![]()

Emily Grubert, Assistant Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Georgia Institute of Technology

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.