RSV: A pediatric disease expert answers 5 questions about the surging outbreak of respiratory syncytial virus

Jennifer Girotto, University of Connecticut

Respiratory syncytial virus, more commonly known as RSV, sends thousands of children to the hospital every year in the U.S. But during September and October 2022, health professionals across the country have watched an unprecedented spike in the number of cases of this usually mild, but occasionally dangerous, respiratory infection in children. Jennifer Girotto is a pharmacist who studies pediatric infectious diseases. She explains how RSV infects the human body, who is most at risk and what might be causing this year’s outbreak to be worse than normal.

1. What is respiratory syncytial virus?

RSV is a common, RNA respiratory virus that affects about 2 million children under 5 years old annually nationwide. Researchers think that most children have been infected by age 2. Like the flu, in most areas of the U.S., RSV usually circulates from November through March and then mostly disappears during the summer months, with only sporadic cases being seen.

2. Who is most at risk?

For most people, especially those who have had an RSV infection in the past, the virus only causes mild symptoms like cough, runny nose and fever, with instances of wheezing and decreased appetite more common in young children.

But young infants, especially those under 6 months old, born prematurely or with congenital heart, lung or other health issues are at increased risk for more severe symptoms. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that 1% to 2% of infants younger than 6 months who get infected with RSV require hospitalization. In an average year, around 250 children die from the disease.

In recent years, researchers have found that RSV can also cause severe disease in high-risk adults and people older than 65..

3. How does RSV make people sick?

The main reason RSV sends babies and young children to the hospital is because the virus infects and kills surface cells within small sacs of the lungs. The body responds by increasing the production of mucus and fluid in these areas. But the extra mucus can plug up and obstruct these parts of the lung and make it so that an infant doesn’t get enough oxygen.

A second common cause for hospitalization due to RSV is pneumonia, where a person’s lungs fill up with fluid. The pneumonia can either be triggered by the virus itself or by a secondary, bacterial infection. Finally, some infants get so sick that they struggle to eat and are unable to take in sufficient nutrients, eventually landing them in the hospital.

4. How concerning is this year’s outbreak?

On average, RSV sends about 60,000 young children to the hospital each year in the U.S. In 2022, however, the virus has hit early and hard. According to the CDC, doctors have found more cases in each week of October than any week in the prior two years.

Health officials aren’t yet sure why the outbreak is so bad this year, but the COVID-19 pandemic may have something to do with it. Some research has shown that seasonality of RSV has shifted. In 2021, RSV infections started much earlier than normal, and over the summer of 2022, they never quite went away. One theory as to why RSV season is starting earlier and hitting harder is that, due to social distancing measures since 2020, an unusually high number of infants and children are experiencing their first exposures and infections at once.

5. How can you protect against catching RSV?

Like colds and the flu, RSV infections spread when people touch dirty surfaces or from respiratory droplets, when an infected person coughs or sneezes.

Health professionals recommend that premature infants and infants with certain medical conditions take a monthly monoclonal antibody medication, called Palivizumab, during the RSV season to help keep them out of the hospital. There are a few RSV vaccines under development, but none are yet approved. For now, preventative measures are the best way to avoid an infection.

If someone is sick with symptoms that look like a cold, it may be best to avoid close contact until they feel better, especially if you have young children or high-risk people around.![]()

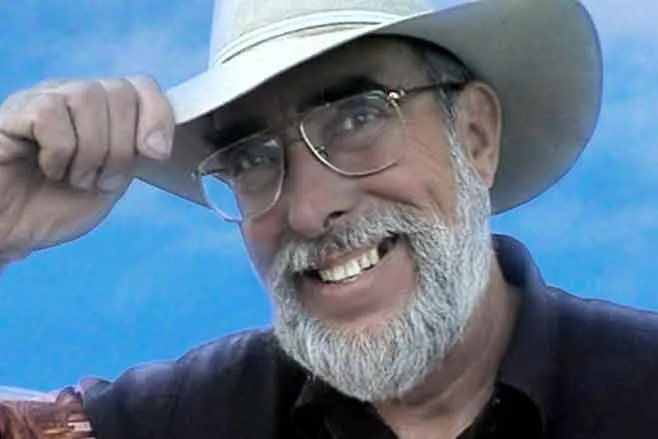

Jennifer Girotto, Clinical Professor of Pharmacy Practice, University of Connecticut

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.