They're not all racist nut jobs – and 4 other observations about the patriot militia movement

Hollee S. Temple, West Virginia University and John Temple, West Virginia University

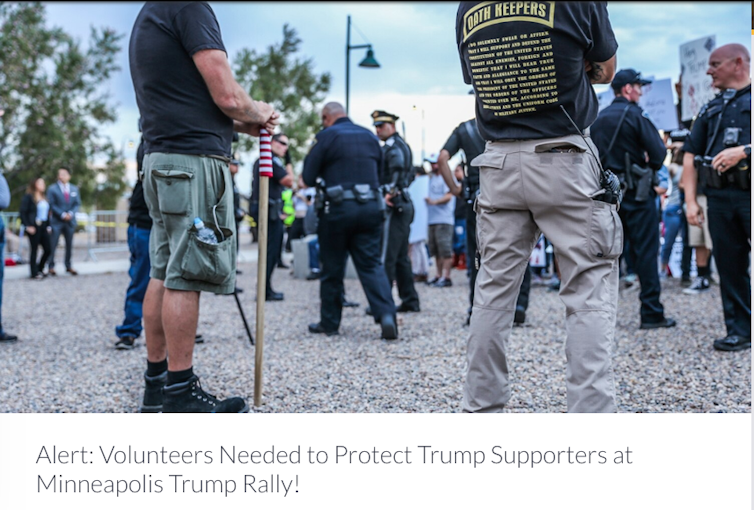

The so-called patriot movement is grabbing headlines once again, as its members pledge to protect Trump supporters at the president’s campaign rallies across the country.

For the past three years, we have studied the rise of the patriots while reporting, writing and editing a nonfiction book, “Up In Arms: How the Bundy Family Hijacked Public Lands, Outfoxed the Federal Government and Ignited America’s Patriot Militia Movement.”

The patriot movement is a fragmented and fractious coalition of groups that distrust the federal government. Members believe the government is impeding their “land rights, gun rights, freedom of speech and other liberties.”

As the book took shape and we talked about our reporting with friends and colleagues, most were dismissive of the people at the center of the story: Cliven and Ammon Bundy.

The Bundys are Mormon ranchers who became the movement’s guiding lights after the 2014 standoff at Bundy Ranch and 2016 occupation of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge. Our friends and colleagues saw the Bundys and their supporters as “racist nut jobs” and nothing more. As reporter Kevin Sullivan wrote in a 2016 story for the Washington Post, law enforcement agrees with this assessment, calling the patriots “dangerous, delusional and sometimes violent.”

While these descriptors certainly fit individual patriots, our take on the movement is less black and white. Here’s what we learned:

1. The so-called “patriot movement,” also known as the “patriot militia movement,” isn’t really a movement and is not made up entirely of militia members.

While movements are usually associated with a specific ideology or shared purpose, that’s not quite the case with the patriots. They are motivated by a varied and sometimes conflicting array of issues. Many focus on gun rights and immigration; others get riled up about privacy, taxes or government overreach. They disagree often and are united only by a general resentment of the federal government.

Even the patriots’ chosen name reflects the disjointed nature of their union. Because some anti-government groups were (and continue to be) associated with racist and anti-Semitic causes or violence, leaders adopted the “patriot” name for public relations purposes in the 1990s.

And many who identify as patriots support but do not officially belong to militias, which are organized paramilitary groups that believe they are the last line of defense against an overreaching federal government.

2. Each group has its own agenda, but they are united by a fear of environmental regulation.

The Bundys love to remind anyone who will listen that almost half of the landmass of the western states is controlled by the federal government.

The patriots have created a corresponding master theory about what they see as an unconstitutional land grab: A small group of global, ultra-wealthy people is purposely implementing environmental regulations and gun laws to make it impossible for rural Americans to earn a living or fight back. Patriots believe those elites want the land, the gold, the oil and the coal for themselves.

In June, Oregon Republican lawmakers fled the State Capitol so there wouldn’t be the quorum needed to vote on a climate change bill that would have forced companies to adopt technologies to reduce overall pollution. The legislation was extremely unpopular with rural voters and patriot militia groups who said they were guarding multiple senators who had holed up in Idaho. The Oregon State Capitol shut down amid fears that militia groups would cause chaos.

Cliven Bundy himself first clashed with the federal government in the early 1990s, when federal land agencies instituted new environmental regulations that would have made it financially impossible for him to continue ranching.

Almost all of the other ranchers in his area sold their operations, but Cliven took another tack: He quit paying grazing fees to the federal government and declared that the feds shouldn’t own land in the first place. This set up the clash, two decades later, that made him a leader in the patriot movement.

3. Some groups are stubbornly bigoted, but others hate to be seen as racist.

Patriot groups tend to be nearly all white and mostly male, with at least one notable exception. We encountered only a handful of people of color during our reporting of “Up In Arms.” We also met many patriots who wished their organizations were more diverse, if only to better counter the perception of widespread racism in their ranks.

This is especially true for the Bundys. Weeks after the 2014 standoff, Cliven gave an infamous speech to his supporters about “the Negro,” suggesting that African Americans might have been better off under slavery. Politicians and media figures who formerly supported Bundy backed away en masse. Video of Cliven’s speech shows an old man who, however offensively, appears to be trying to embrace minority communities and bring them into the anti-federal government fold.

Some patriots have renounced racism and anti-Semitism, seeing those as drags on their more-popular pro-gun and anti-federal government messages. That said, we witnessed an uptick in anti-Muslim and anti-Latino online activity among individual patriots, especially after Trump’s election.

4. Patriots are not all Trump supporters.

A few months after Trump took office, we witnessed an argument at a patriot gathering over one man unfurling a Trump flag. No matter how much Trump seemed to share the patriots’ loathing of the federal government, he was now that government’s leader, and certain purists couldn’t abide it.

The Bundys have a complex relationship with Trump. In 2014, when he was still a developer and reality TV star, Trump announced his allegiance with what Fox News had labeled “Team Cliven Bundy.”

“I like (Cliven’s) spirit, his spunk,” Trump said on Sean Hannity’s show, “and I like the people that – you know, they’re so loyal…”

But during the 2016 campaign, Cliven, a devout Mormon, was disturbed by political advertisements that showed Trump speaking crudely about women and seemingly mocking a disabled reporter. On the other hand, Trump supported the Second Amendment and exhibited disdain for the federal government. In November 2016, the Bundy Ranch blog posted a somewhat oblique Trump endorsement, a picture of Cliven on horseback hoisting the Stars and Stripes under the superimposed words: “Blow your ‘Trumpence!’ VOTE! VOTE! VOTE!”

But two years later, Cliven’s son, Ammon, surprised many when he disavowed Trump’s anti-immigrant rhetoric.

Complex makeup

As the patriot movement returns to the public eye, it is important to understand that its members’ political views – including a profound distrust of government and environmental regulations – have a long history in the U.S.

Further, those views are not monolithic. Many of their ideas are from the fringe of political debate. But during the time we spent talking to patriots, we found that, despite public perceptions, few appeared to be mentally ill or outwardly racist. Instead, their grievances and principles stem from a range of motivations, personal circumstances and political philosophies.

[ Like what you’ve read? Want more? Sign up for The Conversation’s daily newsletter. ] Screen reader support enabled.![]()

Hollee S. Temple, Teaching Professor of Law, West Virginia University and John Temple, Professor, Reed College of Media, West Virginia University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.