Ukraine’s information war is winning hearts and minds in the West

Michael Butler, Clark University

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has dominated headlines since late February 2022. The war struck a nerve among Western audiences, evoking a high degree of support for Ukraine.

The reasons for the prominence of the war in the West are many and varied.

A ground war in Europe launched by a major military power evokes the ghosts of World War II. This is especially true when the attacking country has designs on territory it considers integral to its nation, and is led by a personalist authoritarian regime where all power is concentrated in a single leader. The deep involvement of the U.S. and European countries, both individually and collectively through NATO and the European Union, also inspires Cold War comparisons.

The resulting humanitarian crisis, including the mass exodus of over 5 million refugees, underscores the ethical and moral implications of the war.

These historical analogies and simplifying ideas help explain why the West’s imagination has been captured by this war.

But there’s more to the West’s captivation with the war than is immediately apparent. As a scholar of armed conflict and security, I also find a compelling explanation for why the West is so focused on Ukraine in the Ukrainian government’s ability to provide information about the war in a way that appeals to Western sensibilities.

Weaponizing information

Russia’s use of propaganda and symbols during the conflict, most recently in the “Victory Day” celebrations attempting to draw its own distorted parallels to World War II, has gotten a lot of attention. In the process, Ukraine’s skillful use of information warfare should not be overlooked.

Information warfare entails one party denying, exploiting or corrupting the delivery and function of an enemy’s information. It is used both to protect oneself against the enemy’s information and to create a favorable environment for one’s own information.

With the charismatic President Volodymyr Zelenskyy leading the way, Ukraine’s savvy use of traditional and social media as well as direct appeals to the U.S. Congress, European Parliament and the court of world opinion have provided a clear and compelling framing of the war.

That frame is structured around five affecting themes: the inherently just cause of Ukrainian self-defense; the tenacity of Ukrainian resistance; the barbarity of Russian conduct; Russia’s flawed military strategy and general ineptitude; and Ukraine’s desperate need for more, and more sophisticated, military hardware.

Ukraine’s successful strategy in the battle over information demonstrates the connection between armed conflict and information warfare. Ukraine has forged a stalemate with Russia by stressing these themes of a just war for national liberation using not only traditional tools of warfare – bullets, missiles, tanks – but also by shaping the Western public’s perceptions of the war.

Learning from the enemy

The information front in the Russia-Ukraine war is nothing new. It was opened by Russia in 2014 during its annexation of Crimea and incursion in the Donbas region. Russia took the offensive to cover up its territorial aims, saying instead that it was there to protect civilians and resist the further spread of Western imperialism.

At the time, Ukrainians and Russians alike were buffeted with this disinformation through Russia’s state-controlled international English-language service RT and viral videos on YouTube and various social media outlets.

Since then, Ukraine’s security and defense establishment has focused on improving its ability to counter such disinformation tactics. Zelenskyy’s surprise landslide victory in the 2019 presidential election gave Ukraine what has proved to be its biggest asset. A skilled communicator and performer, Zelenskyy regularly and effectively uses available information to present Ukraine’s version of the war and debunk Russia’s. His initial selfie videos from the streets of Kyiv underscored Ukrainian bravery and unity in a war of self-defense – “the citizens are here, and we are here.”

Zelenskyy’s mid-March virtual address to the U.S. Congress drew a direct line from Russian atrocities – featured in a graphic video clip he showed to lawmakers – to the need for the West to “do more.” His address to the U.N. in early April expanded the scope and terms of the war, defining it as an existential struggle against tyranny and evil and for the very soul of the U.N.:

“If this continues, the finale will be that each state will rely only on the power of arms to ensure its security, not on international law, not on international institutions. Then, the U.N. can simply be dissolved. Ladies and gentlemen! Are you ready for the dissolving of the U.N.? Do you think that the time of international law has passed? If your answer is no, you need to act now, act immediately.”

Getting by with a little help …

Ukraine’s use of the techniques of information warfare as well as its compelling messaging and messengers account for much of its success on that front. Among those messengers are former champion boxers the Klitschko brothers, one of whom is the mayor of Kyiv, and both of whom are now prominent advocates for the defense of their country.

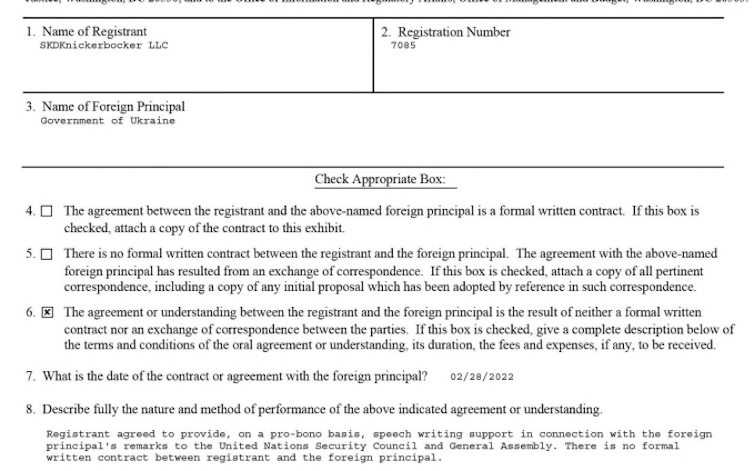

Ukraine has also benefited from pro bono public relations services from major Washington, D.C., firms such as 5WPR and SKDK as well as some of their U.K. counterparts.

SKDK’s managing director, Anita Dunn, served as senior adviser to President Joe Biden throughout his presidential campaign and in the early months of his administration and is reportedly returning to the White House in advance of the upcoming midterm elections. SKDK assisted in drafting Zelenskyy’s speeches condemning Russian aggression and war crimes to the U.N. General Assembly and Security Council. This parallels pro bono legal support from Washington, D.C., law firms such as Covington & Burling, which filed a brief to the International Court of Justice on Ukraine’s behalf in March.

The limits of framing

In a textbook example of hybrid warfare – warfare fought in domains other than the physical battlefield – Ukraine has transformed successes on the information battleground into effective defense of its homeland from Russian aggression. The West has massively increased its support of the country through weapons shipments, intelligence sharing and other aid.

Still, questions remain about the long-term viability of this strategy. Can Ukraine’s strategic use of information continue to offset Russia’s material advantages?

By definition, information warfare obscures and distorts reality in order to tilt perceptions of a conflict to a country’s advantage. Paraphrasing an age-old adage, the war between Russia and Ukraine is a reminder that the first battle in contemporary wars may be for the truth.![]()

Michael Butler, Associate Professor of Political Science, Clark University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.