What baseball can learn about COVID-19 case spikes and crowd size from the NFL’s 2020 season

Alex R. Piquero, University of Miami and Justin Kurland, The University of Southern Mississippi

Baseball season is here, and thousands of cheering fans are back in the ballparks after a year of empty seats and cardboard cutouts as fan stand-ins. Still cautious of the COVID-19 risk, most teams were keeping season openers to 20-30% capacity. Only the Texas Rangers planned a packed stadium for its home opener on April 5, a move President Joe Biden called irresponsible.

It isn’t just baseball – college basketball was allowing up to a quarter of seats filled for Final Four games, soccer season starts April 17, and promoters are planning professional fights in filled-to-capacity arenas.

Many of these attendance decisions are being made with minimal data about the heightened risk that players and fans face of getting COVID-19 at stadiums or arenas and spreading it the community.

There is one large-scale experiment that can offer some insight: the National Football League’s 2020 season.

The NFL played 269 games in 30 cities, some with thousands of fans on hand, others with none. To help everyone understand the risks, we and other colleagues who study large-scale risks to professional sports crunched the numbers. What we found can help teams and fans decide how best to enjoy their favorite games.

How many fans is too many fans?

Twenty of the 32 NFL franchises allowed fans in their stadiums during games. A few of those games had upwards of 20,000 people.

The NFL’s decision to allow fans at games enabled us to examine the potential influence that large sports events can have on local viral transmission. Although we could not definitively assess cause and effect, the results were striking.

We found that in counties where teams had 20,000 fans or more at games, there were more than twice as many COVID-19 cases in the three weeks after games compared to counties with other teams. The case rate per 100,000 residents was also twice as high. Neighboring counties also experienced higher case counts and rates in the three weeks following games with lots of fans in the seats.

By comparing COVID-19 case data and game attendance data reported by ESPN, we found patterns that carried across the 30 football communities. The study has been submitted to the medical journal The Lancet for peer review and was released April 2 in preprint format.

We found very little evidence of COVID-19 spikes associated with fan-attended games in the first seven days after games, which wasn’t surprising given the incubation period of the virus. However, the two-week and three-week windows after games were markedly different, with a significantly greater rate of spikes in COVID-19 cases being identified in communities that had fans at games compared to those that did not.

When stadiums had fewer than 5,000 fans in the stands, we didn’t see elevated case numbers like we did in those that permitted more than 20,000 fans.

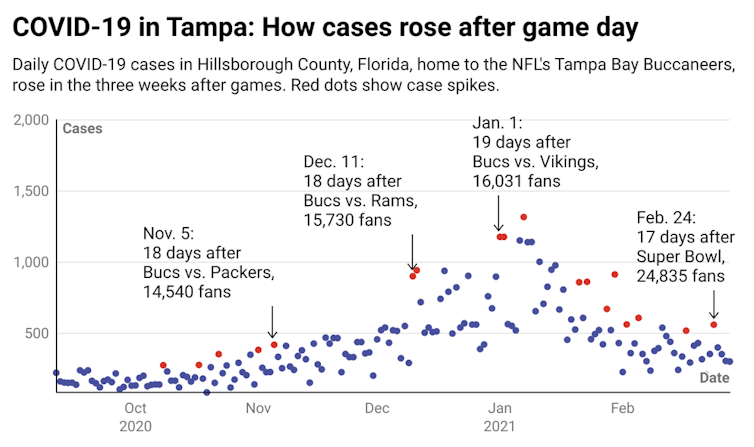

The Tampa Bay Buccaneers, host of the Super Bowl, was one of the teams that permitted the maximum number of fans. The spikes observed in Hillsborough County, Florida, after home games were quite pronounced. Roughly 18 to 21 days after nearly every home Bucs game with fans in attendance, there was a spike in cases. This repeated pattern of spikes in COVID-19 case rates reflects the time between exposure and the illness developing, being tested and reported. A similar pattern appeared across nearly every team that allowed over 5,000 fans in the stadium this past NFL season.

Yes, there’s still a risk

While COVID-19 vaccinations are ramping up nationwide, much of the public is still vulnerable to this lethal disease. As of April 1, only about 17% of the U.S. population had been fully vaccinated. How many people may have natural immunity from having gotten the virus and how long immunity will last isn’t known.

Being outdoors does lower the risk compared to being in a room, but when infected people are shouting or cheering, they can spread the virus farther.

Major League Baseball is encouraging precautions this season, including recommending fans and players wear masks while they aren’t on the field and practice social distancing. But it will be up to each team to decide how tightly packed their fans can be.

The takeaway for games and large gatherings

The 2020 NFL season carries important lessons about mass gatherings during infectious disease outbreaks.

The research suggests using a phased approach, with the number of fans attending sports and entertainment events slowly increasing only after officials have evaluated the COVID-19 case spread in the local and surrounding communities. Such an approach may be necessary until enough people are vaccinated to stop the spread of the virus. Even then, sports teams and event planners should still monitor public health data for future risks.

[You need to understand the coronavirus pandemic, and we can help. Read The Conversation’s newsletter.]

The number of COVID-19 cases in the U.S. has dropped significantly since its peak after the Thanksgiving and winter holidays, but the risk isn’t gone. The daily case count is still higher than last September, and the U.S. is also seeing a rise in coronavirus variants that spread more easily than the initial virus.

Fans and sports and other event planners will need to take all of that into account as they make decisions about upcoming seasons, concerts and the Summer Olympics. That includes a boxing match expected to be attended by more than 60,000 spectators in Dallas over Cinco De Mayo weekend.

NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell has already said he expects full stadiums when football season starts again in the fall.

Wanda Leal of Texas A&M San Antonio, Erin Sorrell of Georgetown University and Nicole Leeper Piquero of the University of Miami contributed to this article.![]()

Alex R. Piquero, Chair of the Department of Sociology and Arts & Sciences Distinguished Scholar, University of Miami and Justin Kurland, Director of Research, National Center for Spectator Sports Safety and Security, The University of Southern Mississippi

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.