What Mary Shelley's Frankenstein teaches us about the need for mothers

Richard Gunderman, Indiana University

Motherhood is getting considerable attention, even if much of the news is concerning. Fertility rates are falling in America as millennials decide not to have children. This should hardly come as a surprise. The cost of raising a child to adulthood has been increasing and real median household income has only just regained its 1999 level.

At this time, when it could be argued that maternity is in decline, Mary Shelley’s classic work of literature, “Frankenstein,” celebrating its 200th anniversary this year, invites us to reflect on the deeper importance of mothers in our lives.

Shelley, who published the work at the age of only 19, had many reasons to make motherhood a major theme. Her mother, the feminist Mary Wollstonecraft, had died from complications arising from her birth. Shelley’s own attempts at motherhood would result in multiple miscarriages and the deaths of three children. Not surprisingly, mothers in “Frankenstein” are conspicuous by their absence – with disastrous consequences.

The creation of Frankenstein

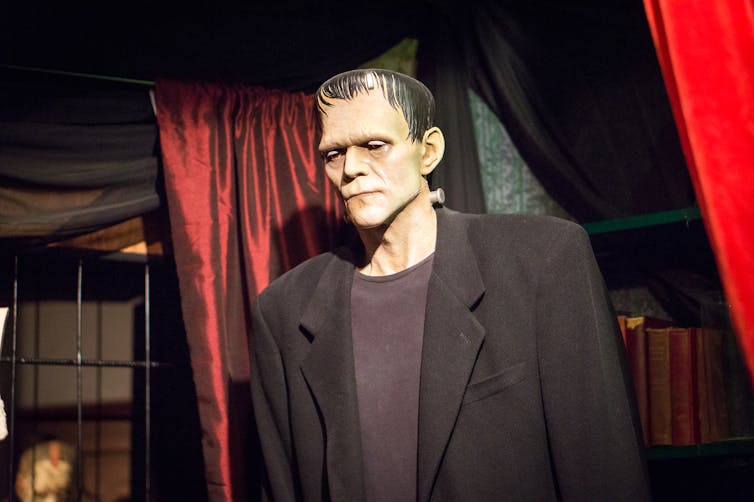

Frankenstein tells the tale of young scientist Victor Frankenstein, who is so horrified at the prospect of death that he seeks a means of restoring life to the deceased. He creates an 8-foot-tall humanoid creature, whose appearance renders it loathsome to all and to which he never gives a proper name. Spurned by its creator, the creature develops a desire for revenge and soon takes the lives of everyone dear to Victor.

At numerous points, the novel highlights the devastating effects of maternal absence.

To begin with, mothers in Frankenstein are quite short-lived. Victor Frankenstein’s mother, an orphan, dies of scarlet fever while nursing Victor’s “cousin” and eventual wife, Elizabeth. While on their honeymoon, Elizabeth too is killed by the monster. Justine, the Frankensteins’ housekeeper, is falsely convicted of the murder of Victor’s younger brother, also grows up motherless.

Frankenstein’s most dramatic instance of motherlessness is the monster itself, a human being created by a man alone. Reflecting on this feat, Victor remarks that “no father could claim the gratitude of his child so completely” as he would deserve of the new race of creatures he sought to create.

Simply put, he devises a new way of bestowing life that completely sidesteps the need for conception, pregnancy and childbirth.

Yet Victor had not done away entirely with the need for maternity. For though he had “selected the creature’s features as beautiful,” the moment he beholds it stirring, he recoils.

“The beauty of the dream vanished, and breathless horror and disgust filled my heart.”

Unbound by any maternal affection or calling, Victor is “unable to endure” the being he had created and rushes out of the room. His creation was never part of him, and he feels at liberty to abandon it.

When the creator matters more

The roots of the problem lie largely in the fact that Victor has moved procreation from the domain of the natural – the purview of Mother Nature – to that of the technological.

His quest is a purely scientific one – a study of chemistry, anatomy and the decay of the human body. It is so devoid of any regard for the sanctity of life that Victor came to regard a churchyard as nothing more than a “receptacle of bodies deprived of life,” implying that a living child might be little more than a body not yet deprived of life.

To him, there is nothing mysterious about life and death. The animation of lifeless matter looms before him as nothing more than a daunting but purely technical challenge. He dreams of the power “to renew life” and becomes so engrossed in this one pursuit that his eyes “become insensible to the charms of nature,” including the unfolding of the seasons around him. A “single great object” swallows up “every habit of his nature.” In short, his scientific quest has left him with no appreciation for life’s beauty and mystery.

What long reigned as one of the most mysterious and awe-inspiring experiences in human life – the birth of a human being – has in Victor’s mind become little more than proof of his own greatness:

“I was surprised that among so many men of genius who had directed their enquiries toward the same science, I alone should be reserved to discover so astonishing a secret.”

To Victor, the act of creation says much less about the creature than the creator.

Devoid of the feminine, bringing forth new life becomes a completely masculine act, an exercise of mastery and control over a reluctant but ultimately compliant nature. Victor’s cold detachment from his creation contrasts sharply with the experience of childbirth as described by those who have been through it – a description not of conquest but endurance and the unfolding of something that resists control.

The experience of labor and birth

Consider this account of labor by the 20th-century activist Dorothy Day in her essay, “Having a Baby: A Christmas Story”:

“Where before there had been waves, there were now tidal waves. Earthquake and fire swept my body. My spirit was a battleground on which thousands were butchered in a most horrible manner.”

It is not difficult to imagine Day having just read Frankenstein’s account of bringing forth new life when she penned these lines about men giving birth:

“‘What do they know about it, the idiots?’ I thought. And it gave me pleasure to imagine one of them in the throes of childbirth. How they would groan and holler and rebel. And wouldn’t they make everybody else miserable around them?”

In Day’s account, gestation and child birth are not like pushing buttons on a control panel but a journey along which the mother is swept – something she does not so much choose as endure. And when it is over, she is presented with a baby fashioned less by her than in her and through her. The form of the baby, from its generic sex to its distinctive features, is a joyful surprise even to the woman who has served as the home of its development for over three-quarters of a year.

For Victor, the process is quite different. He too is surprised, but his surprise reflects the fact that, although he has in fact painstakingly selected each of the creature’s features, the end result turns out radically different from what he envisioned. He thought every aspect of the creature was subject to his control, but instead of a superman he has produced a monster. His horror is magnified by the fact that his creature is his product, while Dorothy Day receives her daughter as something more akin to a gift.

What does a mother add?

Thanks to “Frankenstein,” we can pose a question the answer to which would have seemed obvious throughout most of the course of human history: What does a mother add? The answer, in simplest terms, is that mothers add to life something that Victor Frankenstein – who treats the whole process of creation as nothing more than a challenge to his own ingenuity – is unable even to recognize, let alone wield: the power of a love that puts creature before creator.

Victor has made something new, but it was never a part of him, and from the moment he lays eyes on it he seeks to disassociate himself from it. Because the creature’s appearance disappoints him, he feels within his rights to turn his back on it – to abandon it to a world utterly unprepared to receive it. The circumstances of the creature’s birth may be monstrous, but it is not yet a monstrosity. Only by depriving it of any semblance of love does Victor create a true monster.

By showing us a world from which mothers are largely absent, Mary Shelley reminds us that the genius of motherhood lies less in biological reproduction than in the capacity to love. Human beings need love to develop and thrive. We honor this capacity of mothers when we say that someone has a face that “only a mother could love.”

![]() Perhaps Victor’s creature would never had developed into a monster in the first place, if only it had enjoyed the love of a mother.

Perhaps Victor’s creature would never had developed into a monster in the first place, if only it had enjoyed the love of a mother.

Richard Gunderman, Chancellor's Professor of Medicine, Liberal Arts, and Philanthropy, Indiana University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.