Why using reconciliation to pass Biden's COVID-19 stimulus bill violates the original purpose of the process

Naomi Schalit, The Conversation

Reconciliation – it’s a term federal budget experts would understand, but for the rest of us, it sounds like what you do with a family member you haven’t talked to in years. It’s also the process congressional Democrats plan to use to pass President Joe Biden’s US$1.9 trillion COVID-19 rescue and stimulus bill in the Senate. We asked Raymond Scheppach, who is a public policy scholar at the University of Virginia and a former deputy director at the Congressional Budget Office, to describe reconciliation and explain why its use now is causing such controversy.

What is reconciliation, and how is it used in Congress?

Reconciliation is a legislative process originally intended to reduce federal budget deficits. In 1974, lawmakers decided they had to deal with a recurring problem: If more money was spent than expected or revenues didn’t meet projections, the nation’s deficit grew. But lowering deficits is politically difficult; to do it, Congress needed to either increase revenues, cut spending or both. That usually meant reducing entitlements and other mandatory spending – like nutrition assistance for children – or increasing taxes.

So legislators created this process called “reconciliation” that could be used to reconcile actual spending with Congress’ previously adopted spending targets.

Here’s the key part that addressed the problems legislators faced when cutting spending or hiking taxes: Budget moves made under reconciliation could not be filibustered. Lawmakers believed this could ease the political difficulty associated with lowering deficits over the long term.

An important point: Reconciliation could be used only to change taxes, mandatory spending like farm price supports and entitlements such as Social Security or Medicare.

Does using reconciliation for the COVID-19 bill represent a hijacking of the original purpose of the process?

It’s important to look back at the 1974 Act to determine the purpose of the reconciliation provision and how it has changed over time. A provision that was created in 1974 to reduce deficits is now being used to do the opposite: dramatically increase deficits.

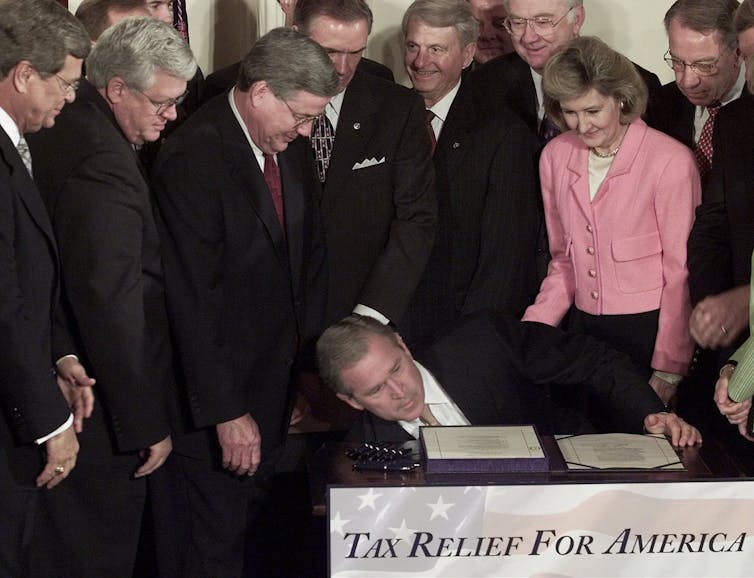

So contrary to reconciliation’s original purpose, it was used for the 2001, 2003 and 2017 tax cuts, which substantially increased deficits. Congress could do that because the restrictions on reconciliation’s use in the Senate have been reduced over time so that now major tax cuts or omnibus spending bills are allowed.

It was also inappropriately used to pass modifications to the Affordable Care Act, which significantly increased spending even though it also raised revenues sufficient to offset the spending. Even though it was budget-neutral, it did not reduce the deficit. The $1.9 billion Biden COVID-19 bill would also be an inappropriate use relative to the original intent of the provision, as it would substantially increase the deficit.

How often has reconciliation been used?

The reconciliation provision has been used by both parties more than 21 times since the 1980s. In some cases, such as the 1990 and 1993 Omnibus Reconciliation Acts, whose major purpose was to cut spending and increase revenues, each reduced the deficit by a little over $700 billion over five years.

For President Biden and the Democrats on Capitol Hill, there are some clear advantages in using the reconciliation process. It would make consideration of the $1.9 trillion bill privileged, in legislative terms. This means that debate can be limited, but most importantly it can’t be filibustered in the Senate, as it requires only 51 rather than 60 votes to pass. As long as all 50 Democrats are willing to vote in favor, then the vice president, also a Democrat, can cast the deciding 51st vote.

This process is much more important in the Senate as opposed to the House of Representatives, which has a rules committee that can limit debate and amendments. One fact sheet about reconciliation, produced by the House budget committee in 2020, says “Reconciliation is a tool – a special process – that makes legislation easier to pass in the Senate.”

Are there other reasons legislators would want to use reconciliation?

Because it requires only a simple majority vote, legislation can be passed relatively quickly under reconciliation’s rules rather than going through a time-consuming negotiation to come up with a bipartisan bill. Since most of the money in President Biden’s bill is for coping with COVID-19 and stabilizing a damaged economy, the administration believes timing is critical. The faster the bill can be enacted, the faster schools can fully reopen, vaccines can be administered and the unemployed will be able to find jobs.

Is the COVID-19 stimulus bill the one time we’re likely to see reconciliation used this year?

Under the rules, most years there can only be one reconciliation bill. But because it wasn’t used last year, Biden and the Democrats will be able to do two this year.

This means that they would be able to use reconciliation for this $1.9 trillion COVID-19 bill and then another reconciliation bill later in the year on climate change or infrastructure or any other major priority. There is no sacrificing other major Democratic priorities if reconciliation is used at this time, which is another political advantage – although using reconciliation to pass these policies would again violate the original intent of the process.

Is using reconciliation – devised to avoid political battles – now another form of power politics, ramming legislation through rather than considering the minority’s views?

The Senate often operates on historical precedents, and thus the longer-term questions are: What is the effect of using reconciliation on the Senate as an institution? How does it affect the rights of the minority and even democracy itself?

Perhaps the most significant negative effect is that it has reduced the rights of the minority party to shape legislation, which often leads to more extreme policies. Participation by the minority party in making legislation often forces policy toward the middle of the political spectrum, where most Americans live. But what we are seeing more often now is that the minority party refuses to engage with the majority party on legislation. That can force the majority to go the route of reconciliation.

Yet passing legislation through reconciliation, I believe, exacerbates voter frustration and weakens democracy.![]()

Naomi Schalit, Senior Editor, Politics + Society, The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.