Wildland firefighters face a huge pay cut without action by Congress

Brent C. Ruby, University of Montana

Radios crackle with chatter from a wildfire incident command post. Up the fireline, firefighters in yellow jerseys are swinging Pulaskis, axlike hand tools, to carve a fuel break into the land.

By 10 a.m., these firefighters have already hiked 3 miles up steep, uneven terrain and built nearly 1,200 feet of fireline.

It’s physically exhausting work and essential for protecting communities as wildfire risks rise in a warming world. Hotshot crews like this one, the U.S. Forest Service’s Lolo Hotshots, are the elite workforce of the forests. When they’re on the fireline, their bodies’ total daily energy demands can rival that of the cyclists in the Tour de France, as my team’s research with wildland fire crews shows.

These firefighters are also caught in Congress’ latest budget battle, where demands by far-right House members to slash federal spending could lead to a governmentwide shutdown after the fiscal year ends on Sept. 30, 2023.

After extreme fire seasons in 2020 and 2021, Congress funded a temporary bonus that boosted average U.S. Forest Service wildland firefighter pay by either 50% or US$20,000, whichever was lower. But that increase expires after Sept. 30, knocking many federal firefighters back to earning the minimum $15 per hour.

Legislation to make the raise permanent is pending before Congress, which is now preoccupied. A short-term pay boost may be possible, but that doesn’t solve the long-term pay problem. And if the government shuts down, federal firefighters will likely be working without immediate pay. The National Federation of Federal Employees warns that a large number of firefighters could quit if their pay also drops.

Firefighters push their bodies to extremes

Life on the fireline is demanding. Pack straps dig into the neck and shoulders with each swing of the Pulaski. It’s a constant reminder that everything wildland firefighters need, they carry – all day.

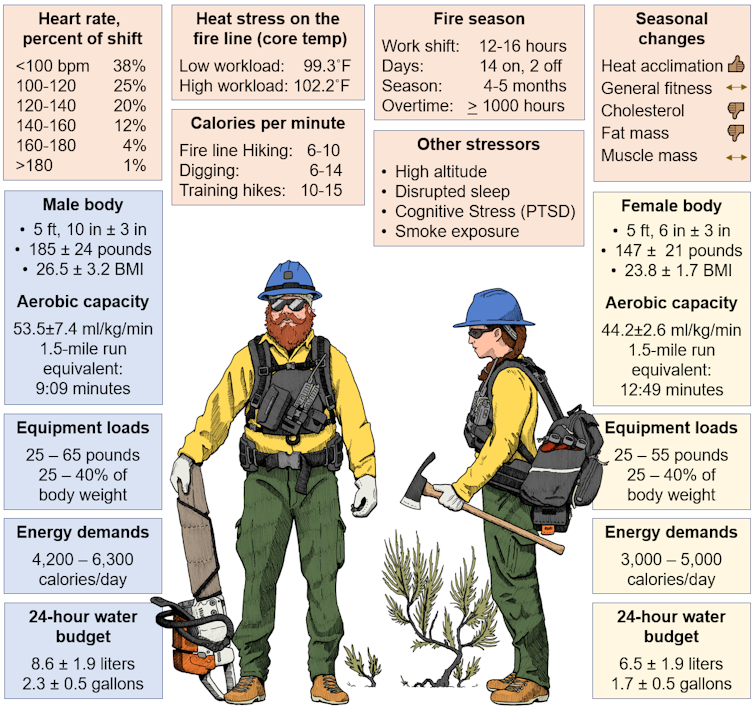

The critical water and food items, supplies, extra gear and fireline tools – Pulaskis, chain saws and fuel – add up to an average gear weight often exceeding 50 pounds.

Hiking with a load and digging firelines with hand tools burns about 6 to 14 calories per minute. Heart rates rise in response to an increased pace of digging.

Measured with the same techniques used to quantify the energy demands of Tour de France riders, wildland firefighters demonstrate an average total energy expenditure approaching 4,000 to 5,000 calories per day. Some days can exceed the Tour’s average of about 6,000 calories, equivalent to around 12 McDonald’s Happy Meals. Add to that a daily water need of 1.5 to over 2 gallons.

This isn’t just for a few days. Fire season in the western United States can last five months or more, with most Hotshot crews accumulating four to five times the number of operational days of the 22-day Tour de France and over 1,000 hours of overtime.

The physical demand of a day on the fireline

My team has been measuring the physical strain and total energy demands of work on an active wildfire, with the goal of finding ways to improve firefighter fueling strategies and health and safety on the line.

The crew members we work with are outfitted with a series of lightweight monitors that measure heart rate, as well as movement patterns and speed, using GPS. Each participant swallows a temperature-tracking sensor before breakfast that will record core body temperature each minute throughout the work shift.

As the work shift progresses, the Hotshots constantly monitor their surroundings and self-regulate their nutrient and fluid intake, knowing their shift could last 12 to 16 hours.

During intense activity in high heat, their fluid intake can increase to 32 ounces per hour or more.

The highest-intensity activity is generally during the early morning hike to the fireline. However, the metabolic demands can sharply increase if crews are forced into a rapid emergency evacuation from the fire.

My team’s research has found that the most effective way for wildland firefighters to stay fueled is to eat small meals frequently throughout the work shift, similar to the patterns perfected by riders in the Tour. This preserves cognitive health, helping firefighters stay focused and sharp for making potentially lifesaving decisions and keenly aware of their ever-dynamic surroundings, and boosts their work performance. It also helps slow the depletion of important muscle fuel.

Although crews gradually acclimatize to the heat over the season, the risk for heat exhaustion is ever present if the work rate is not kept in check. This cannot be prevented by simply drinking more water during long work shifts. However, regular breaks and having a strong aerobic capacity provides some protection by reducing heat stress and overall risk.

The season takes a toll

Hotshots are physically fit, and they train for the fire season just as many athletes train for their competition season. Most crew members are hired temporarily during the fire season – typically from May to October, but that’s expanding as the planet warms. And there are distinct fitness requirements for the job. The physical preparations are demanding, take months and are expected, even when temporary crew members are not officially employed by the agencies.

Still, with the immense physical demands of the job, crew members often experience a decay in metabolic and cardiovascular health and an increase in cholesterol, blood lipids and body fat. It is unclear why such a hardworking job often makes firefighters less healthy, requiring an off-season reset to recover, retrain and rebuild.

The season causes damage. This unfolds counter to the commonly accepted benefits of regular exercise. Pollutant and smoke exposure, lapses in nutrition, sleep disorders and chronic stress during the season seem to gradually poke holes in the Hotshot armor.

Progressive intervention strategies can help, such as educational programs on specific physical training and nutritional needs, mindfulness training to reduce the risk of job-oriented anxiety and depression, and emotional support for crew members and families. However, these require agency and congressional investment, a commitment beyond ensuring pay raises remain intact. Removing either is synonymous with taking away critical tools for the job on the firelines.

Developing offseason practices that pay close attention to both physical and mental health recovery can help limit harm to firefighters’ health. Many Hotshots have bounced back and returned season after season. However, a government shutdown and failure to act on pay with no thought to the health and safety of front-line fire crews could worsen crew retention in an already dwindling workforce.

This is an update to an article originally published Aug. 8, 2023.![]()

Brent C. Ruby, Professor of exercise and work physiology, University of Montana

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.