An ambitious plan to stop the rise of superbugs

David Pride, University of California San Diego

Antibiotic resistance is here to stay, but that doesn’t mean we can’t do anything to stop it.

A headline that always catches my attention is that antibiotic resistance is on the rise. Underlying these headlines is that the disease-causing bacteria that make us sick are becoming less responsive to treatment by our most common antibiotics. If you read past the headline, you will see that the World Health Organization (WHO) predicts that by the year 2050, there will be 10 million deaths annually from antibiotic resistant bacteria (ARB). This would place ARB ahead of cancer as a leading cause of death worldwide. Those headlines assume that the world cannot do anything to intervene.

I am a physician scientist trained in infectious diseases who has had a front row seat as ARB has been on the rise. I am also a member of a group of researchers who are developing bacteriophages – viruses that kill bacteria – as alternatives to antibiotics as an additional means to limit ARB in the U.S. and worldwide.

To understand why ARB is approaching crisis levels, it is important to understand the limitations of the antibiotics and what trends are contributing to it.

Antibiotic development has its limitations

People have used antibiotics to treat infections since the early 1940s, but naturally produced antibiotics are millions of years old. These medicines are derived from natural products that bacteria and fungi use to combat other bacteria. They use these products to eliminate their competition.

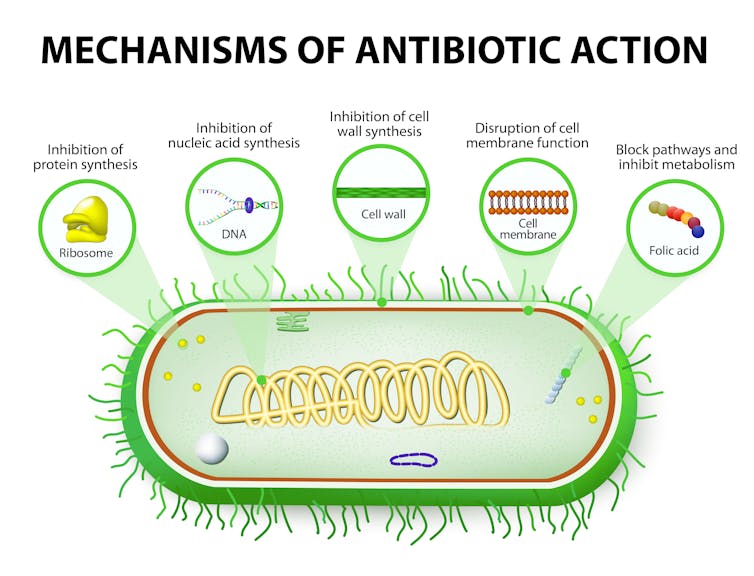

Most of the antibiotics produced by industry have one thing in common: they work the same way. They block the bacteria’s ability to make proteins, DNA, RNA or even its cell wall, the consequences of which are deadly to the bacteria. Thus most new antibiotics are not based on new ways to kill bacteria; they’re simply incremental improvements.

The consequence is that when a bacterium develops immunity to one of these antibiotics, it often gains resistance to that entire antibiotic group. Simply put, a single resistance event can cause us to lose quite a few antibiotics that had previously been effective against that bacterium.

Antibiotic resistance might be right under your nose

Much of the ARB problem is caused by humans. Bacteria often become resistant to antibiotics after exposure to these drugs. The easiest way to think about this concept is, “What can grow, will grow!” You’ve got a body full of microorganisms - called your microbiome - that includes an estimated 38 trillion bacteria. While the antibiotic you take kills the bacterium making you sick, it also kills many of those other good bacteria that are harmless. That leaves you with a microbiome populated by many bacteria that are resistant to not just that single antibiotic, but often that entire group. Because only ARB can grow in this environment, your microbiome becomes populated largely with ARB. Thus, even healthy people who have taken antibiotics in the past may harbor ARB.

The problem gets even worse when you consider all the unnecessary antibiotic use across the world. Doctors use antibiotics in people with viral infections even though they don’t work. Livestock producers feed them to animals to accelerate growth and provide health advantages. More than 70% of all antibiotic use globally is in animals, and you can also be exposed to antibiotics just by handling and consuming meats from animals raised on antibiotics. All these exposures contribute to growing global antimicrobial resistance.

If we know the root causes of antimicrobial resistance, then why is it still occurring? It may seem like physicians and scientists have been sitting and watching this all happen. That’s not correct.

We are not unified

Hospitals in the U.S. are taking steps to limit ARB. For some patients, everyone who comes in contact with them must wear gown and gloves. This practice limits the spread of ARB throughout the hospital. Another control is preventing overuse of our most powerful antibiotics to curb the evolution of ARB. Usually, you have to call an infectious diseases physician like me to get access to these drugs. These two basic components of antibiotic stewardship have been quite effective in limiting ARB.

We still see ARB because not every hospital adheres strictly to these practices, and enforcement of antimicrobial stewardship in hospitals is not uniform.

Amplifying the problem is that some hospitals don’t routinely screen patients for antibiotic resistant microbes. There are patients who carry ARB in their microbiomes and it’s pretty difficult to block the spread if you don’t know who carries them.

These strategies together can limit ARB in a single hospital, a part of town, or even an entire city. But you may still be losing the battle across your state. So what can our leaders do to limit ARB?

How to reduce antibiotic resistance?

The bottom line is that an alternative to antibiotics must be developed. A new industry has emerged that focuses on using viruses to kill bacteria, but these efforts have been inconsistent.

Bacteriophages have been used successfully in a few recent cases to treat ARB. A patient with a severe skin, liver, and lung infection and a man with a life-threatening ARB were both treated successfully with bacteriophages, providing great hope for the future of phage therapy.

However, these cases provide only anecdotal evidence that such therapies can work. They are far from meeting the rigorous standards of efficacy the FDA applies to antibiotics. The government must encourage high quality, reproducible studies supporting the use of these antimicrobial agents to further our understanding of their potential in the treatment of ARB in the larger population.

The U.S. also needs to invest in the development of antibiotics that attack bacteria in novel ways. The government must have a policy of incentives to entice industry to attack this problem because market forces don’t favor huge investments in antibiotic development. The reason is most patients use an antibiotic once every few years for a couple of weeks at a time to treat infections. Compare that to a heart medication that patients must use daily for the rest of their lives; the latter is clearly more lucrative.

Other strategies the U.S. could adopt include uniform screening and antibiotic stewardship practices across its hospitals. Physicians may not like a governing body intervening in their practices, but the U.S. must reduce unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions. And the U.S. must limit antibiotics in livestock. This could have a huge impact.

Finally, once the U.S. implements these efforts, it must export them to the rest of the world. Executing these changes in the U.S. alone won’t reverse this trend; but if we’re serious about altering the trajectory ARB and developing antibiotic alternatives, all options must be on the table.

[ Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter. ]![]()

David Pride, Associate Director of Microbiology, University of California San Diego

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.